In an open letter released December 4, more than 700 artists, authors and arts workers are calling for Toronto to stop evicting underhoused people from public spaces in the middle of a pandemic.

Indu Vashist, executive director of the South Asian Visual Arts Centre, helped canvas the art community for signatures and support in the days leading up to the letter’s public release.

“I felt that arts organizations needed to take the influence that they have and kind of concentrate it, to also do popular education around what is happening in the encampments and put pressure on governments—the city government particularly,” Vashist says in an interview. “We [arts organizations] get used to selling the city all the time, whether it’s for tourism or whether it’s for economic development,” Vashist continues. “But we don’t always flex our muscle for shaping how we want the city to look.”

Yuula Benivolski is a photographer and video artist who signed the open letter and has been working with the Encampment Support Network for several months.

“This [issue] is very personal and close to us,” Benivolski says in an interview. “Artists and poverty and homelessness often intersect. Lots of people I know are just a paycheck away from losing their homes.”

Benivolski credits musician Simone Schmidt and artist Jeff Bierk as being some of the first creators to collaborate with frontline workers in creating the Encampment Support Network in spring 2020.

Here, Jeff Bierk tells Canadian Art more about this particular instance of artist activism—and what needs to be done next.

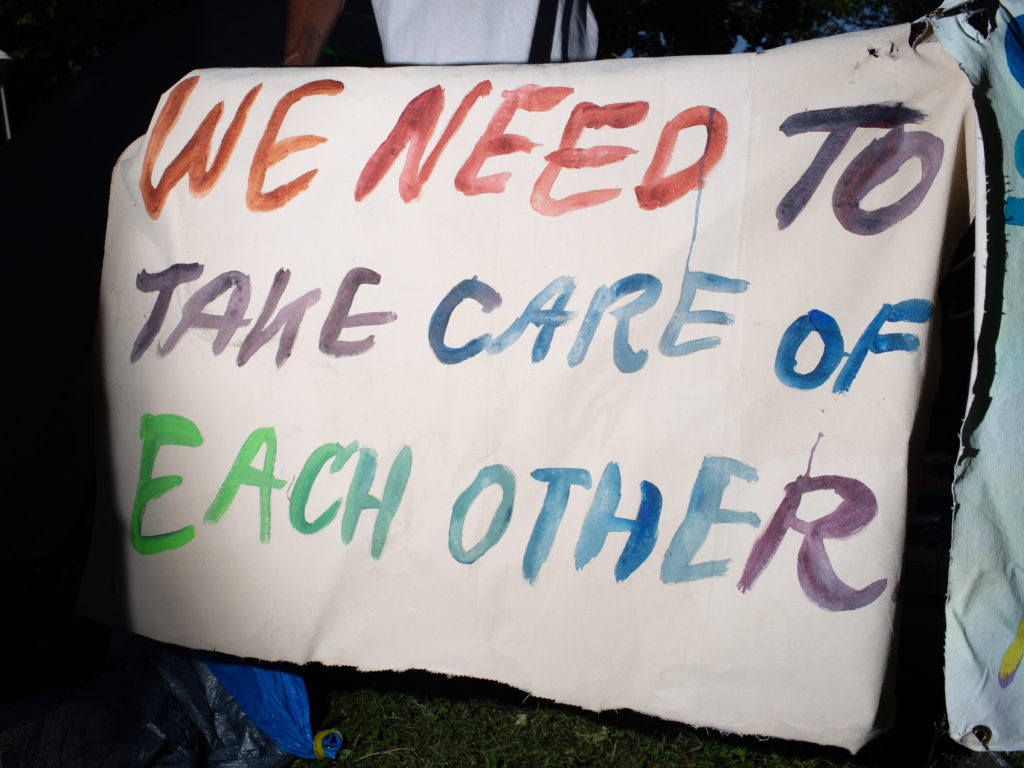

Jeff Bierk, We Need to Take Care of Each Other, with Simone Schmidt and Lil Man, Moss Park, North Side, June 20, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Jeff Bierk, We Need to Take Care of Each Other, with Simone Schmidt and Lil Man, Moss Park, North Side, June 20, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Canadian Art: Is this housing crisis normal or is this not normal?

Jeff Bierk: I think that we’ve always been in a state of precarity when it comes to housing in Toronto. It’s clear that the machine of the city is to develop neighbourhoods, to push people out of neighbourhoods and make buildings and apartments and condos for people with money.

And it seems like the housing crisis is ramping up. It’s getting harder and harder to find accessible space, whether that’s a place to live or a studio or something like that. So it’s not new, and it just feels so amplified by the fact that we’re in a global pandemic.

CA: Could you talk about the Encampment Support Network and how that started?

JB: Early on in, like in the spring, a small group of us responded to a call to support people living underneath the Gardiner Expressway. A very small group of us met to get in the way of the city bulldozers and watch what was happening. We were really struck by the violence of the process, and the other thing that we noticed was that the people who were showing up to support the encampment residents were frontline workers. They were people that had already been working frontline during the first few months of the pandemic, and who had not stopped working. It just seemed like this intense amount of extra work [for them]. And so it was clear that there was a need to support those people living in encampments and also to take a load off the agency workers and frontline workers who had traditionally been showing up to support folks.

ESN started with sign-painting. Frontline worker Tave got residents in Parkdale to write down slogans they wanted and Simone hand-wrote them out, and then a bunch of people painted them. The first kind of action we did was just putting signs up in encampments. And it was just spectacular.

Jeff Bierk, We Need Permanent Housing Now, with Simone Schmidt and Sarah Creskey, Alexander Park, August 13, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Jeff Bierk, We Need Permanent Housing Now, with Simone Schmidt and Sarah Creskey, Alexander Park, August 13, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

CA: In the beginning, how was ESN raising awareness?

JB: We basically took the lead from a bunch of workers. So we started having conversations with harm reduction worker and Overdose Prevention Society member Zoë Dodd and homeless advocate and Indigenous health promoter Les Harper, who had done a lot of work in the east end. We talked to Lorraine and Greg and Doug who work at Sanctuary. And we started to try to collaborate and figure out what the need was. The first iteration of ESN was an encampment-defence network, and then it very quickly turned into providing mutual aid. We set up a place to receive physical donations, of things like tents and water and Gatorade, and we got donations of things like ice and socks and sleeping bags.

Then we formed this group made up of five autonomous neighbourhood committees. We do two things: we provide mutual aid to encampments and politicize that action to show what the city is not providing. The second part is that we act as a kind of a watchdog. We’re able to monitor the city, and monitor the Streets to Homes program within the police. We work under the principle that we’re an abolitionist network, and with the notion that the needs of encampment residents are central to what we do. We operate under the direction and needs of encampment residents.

Early on I remember going for a drive and seeing encampments everywhere for the first time, specifically underneath the Gardiner Expressway. It was just filled with tents. And talking to people who have lived in Toronto longer [than I have], they say it was very reminiscent of 15 or 20 years ago when there was Tent City.

Encampments aren’t new in Toronto. What happened a decade ago was that a lot of grassroots programs turned into city-funded agencies. The city made a bunch of bylaws to make encampments illegal and at the same time, under the umbrella of the city, made all these programs to try to support homeless people.

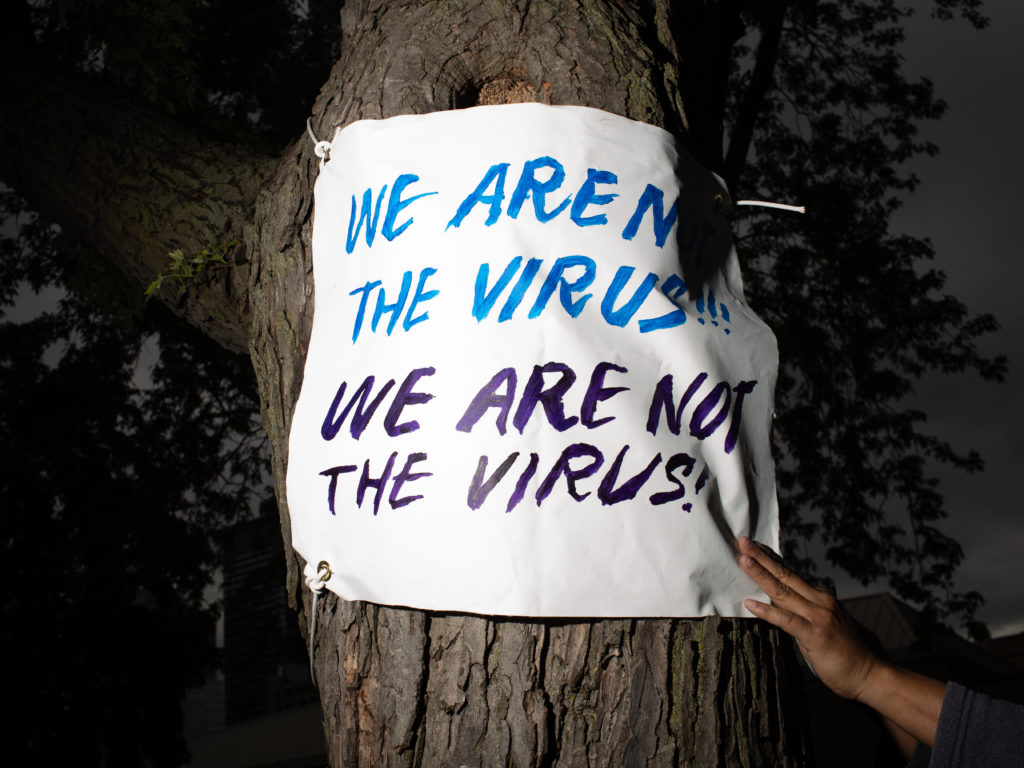

Jeff Bierk, We Are Not The Virus, From Tave and Parkdale, at Moss Park with John Bush, Simone Schmidt and Ginger Dean, May 31, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Jeff Bierk, We Are Not The Virus, From Tave and Parkdale, at Moss Park with John Bush, Simone Schmidt and Ginger Dean, May 31, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

CA: What is the problem with those programs?

JB: This is where it gets complicated. I know specifically from workers I’ve had long conversations with, workers who have been doing frontline work for a long time, that as things get bigger and more structured there’s this loss of connection. A lot of workers talk about how, in the early days, [they didn’t] have the limitations of working for the city or working for an agency. There was a lot more freedom to get people things. When those agencies got centralized it became harder and harder to have personal relationships in terms of supporting people. Right now we have this whole central intake city structure. If someone needs a bed, they have to call a number, [but] there are no beds, and the process to get a bed is ridiculous and it doesn’t work for a range of reasons.

I remember, like years ago, being in a detox and physically seeing four open beds in the detox [centre]. I had a friend who was desperate to go to detox and I asked the people there if that person could get one of the beds, and they were like, “No, you have to call central intake.” The absurdity of that! We were in the fucking place and the bed was visible to us and we called the number and they said there was no bed. That was my first experience with central intake many years ago, and it’s very similar now.

CA: How can things change at a municipal level?

JB: Over 50 people gave depositions at the Toronto City Council meeting on December 7. I spent all day crying because of the heart-wrenching stories of care and love and crisis, and they were speaking to a screen of city councillors and they were showing no emotion. The depositions were to try to convince city councillors to pass the motion to put a moratorium on encampment eviction, which we see as the first step. The encampments are essentially illegal because of bylaws that prevent people from erecting shelters in parks.

The interesting part is to think of how swiftly and easily the city has changed bylaws for businesses during the pandemic. You look at Dundas Street or Queen Street: restaurants were able to so quickly expand their patios into the street; the city put up cones to make that possible. Changing the bylaws happened with no effort. And then what we saw in parks was that bylaws were used as a tool to displace people. What we saw was that police and city workers would come and give eviction notices—sometimes not even giving people 24 hours to leave—and then remove people.

Jeff Bierk, AK and Family, ESN, Moss Park, South Side, October 21, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Jeff Bierk, AK and Family, ESN, Moss Park, South Side, October 21, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

CA: Who were the people at the deputations?

JB: So many different people, frontline workers, volunteers, a lot of ESN people, academics, doctors. It was a time for the public to speak to city councillors with demands. So people were asking for a moratorium on encampment evictions. They were asking for 2,000 new temporary shelter hotel beds, with a priority on central downtown locations. And we were asking for a million dollars to provide encampment residents with survival gear for the winter.

CA: How did the arts community get involved—how did you call them in?

JB: We made a list of demands and we did a call-out to artists to support those demands.

CA: And why do you think artists were willing to support those demands?

JB: I think it’s just common sense, I think it’s basic care. Why would we, why would anyone, co-sign the violent displacement of marginalized people from parks? It’s absurd; it makes no sense. There’s so much money being wasted in the policing and removal of folks, and it would actually just be much easier to find ways to house people.

So many people contact me privately or through the network and they’re stunned about this narrative of artists organizing, but if you look back, it’s not a very spectacular or new thing.

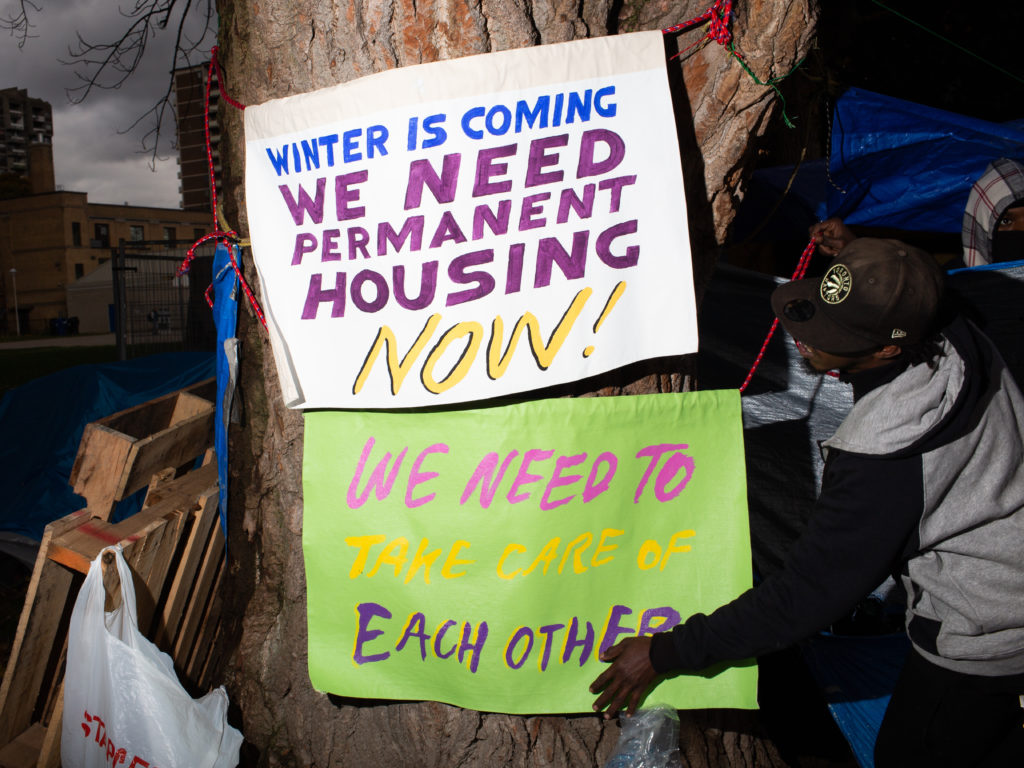

Jeff Bierk, Winter Is Coming, We Need Permanent Housing Now!, with ESN, for AK and Family, Moss Park, South Side, October 21, 2020, 2020. Photograph.

Jeff Bierk, Winter Is Coming, We Need Permanent Housing Now!, with ESN, for AK and Family, Moss Park, South Side, October 21, 2020, 2020. Photograph.