As I step off the bus towards Michael Snow’s house, I feel like I am carrying his entire career in a No Frills bag. Well, maybe not his entire career, but a good chunk of it.

In advance of our interview, Snow has suggested that I dig through Canadian Art’s archives—which also include a treasure trove of copies of our predecessor artscanada (1967–1983) and an earlier magazine also called Canadian Art (1943–1966) to see if I can find a cover he did after winning a contest in 1951, when he was an OCAD student.

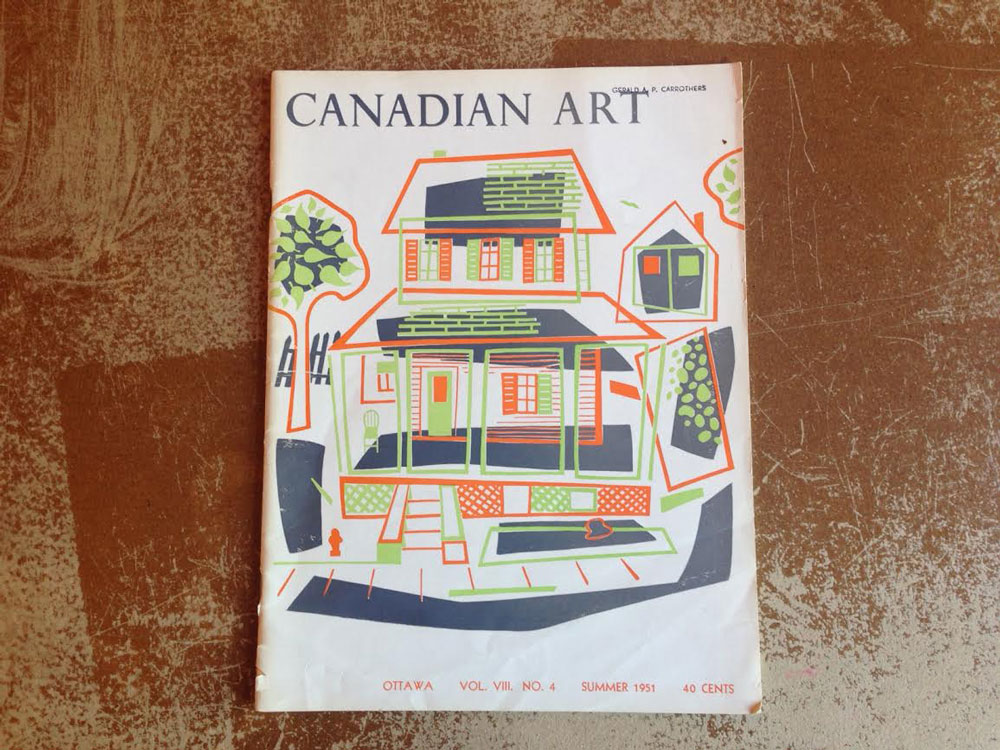

I have found that 1951 cover Snow did as a student—an energetic green and orange work called Ontario House—as well as a 1970 copy of artscanada that featured him on the cover in recognition of his showing at the Venice Biennale’s Canada Pavilion that year. Also in the bag: magazines with cover stories on Snow from Canadian Art’s Summer 1986, Spring 1994 and Summer 2000 editions; printouts of online stories we did about Snow in 2012 (for his AGO sculpture show, “Objects of Vision”) and in 2014 (for “Photo-Centric,” a survey in Philadelphia); and a couple of copies of artscanada that include articles on his practice.

It is appropriate, in many ways, for me to bring the magazines, even if it is not quite appropriate for me to bring them in a grocery bag. Snow is the honoured guest at the Canadian Art Gala this week, and while locating and reading these texts, I have been reminded (as if one needs to be) of the great significance of Snow’s practice to the art world in general and to Canadian art in particular.

As a musician, photographer, filmmaker, painter, sculptor and more, Snow was multidisciplinary well before that was the standard mode of a contemporary artist. Articles from as early as 1970 speak of Snow as “one of the most important aesthetic sensibilities” of the late 20th century. It’s a reputation that has only grown over the years, with exhibitions and screenings still on the go at top museums and galleries worldwide. The No Frills bag weighs heavy in my hand.

Snow sees me coming up the steps, and opens the door before I can knock. As we walk through the living room, I see catalogues of recent shows in Italy and the United States. Among the many artworks lining the walls, I spy a framed print of Snow’s Flight Stop—the Canada geese perpetually in a state of near-landing at Toronto’s Eaton Centre—propped on the floor. As we pass a baby grand in the centre of the narrow room, Snow plonks a finger on one of the keys. I tell him it is a nice piano, and he tells me it belonged to his mother.

We settle in the small kitchen on red upholstered chairs. Glass bottles of various colours line the windowsill. I start taking magazines out of the No Frills bag. We begin the interview, or conversation.

When he was a third-year student at the Ontario College of Art, Michael Snow won a cover competition for Canadian Art‘s Summer 1951 issue. The title of the work? Ontario House.

When he was a third-year student at the Ontario College of Art, Michael Snow won a cover competition for Canadian Art‘s Summer 1951 issue. The title of the work? Ontario House.

Leah Sandals: I’m glad you asked me to bring these magazines.

Michael Snow: I just thought you should refer to them because I was thinking about my history in relation to Canadian Art and it goes a long way back. This cover [pointing to 1951 edition] is from when I was at OCA [the Ontario College of Art].

An interesting thing about this [artwork on the 1951 cover] is that it was influenced by Stuart Davis. I had seen some of his work, and I liked it quite a bit.

And all of a sudden, now, Stuart Davis has a show at the Whitney, and there are references to Stewart Davis all over the place. And I haven’t seen him mentioned for the last 50 years!

LS: It is interesting how things return and recur. The first thing I wanted to ask about is what it might be like for you to see all these publications together, from 1951 to the present day, almost.

MS: Well, it’s wonderful in some ways, because they are all kind of echoes of events—exhibitions and things like Venice. It’s fantastic.

LS: And it’s a lot to consider, I bet.

MS: The thing I like is that I’m still here.

LS: That is a good thing! On a similar note, I’ve noticed much has changed in the world since I became an art student 20 years ago, and I’m assuming much has changed since you were an art student back in 1951—both in the world at large and in the art world in particular. I was wondering what changes in these decades have struck you the most.

MS: Well, the art world was very small in the ’50s in Toronto. In terms of galleries, there were two or three private galleries—the Roberts Gallery, the Picture Loan Society run by Douglas Duncan… and maybe that’s it. This is before Carmen Lamanna and Av Isaacs.

And I do remember knowing about Canadian Art and appreciating the fact that it discussed artists that I might see—that I might even know. Because there was very little of that.

The societies, like the Ontario Society of Artists and the Canadian Society of Painters in Watercolour, they had these quite big group shows pretty much every year, so that was the exhibiting of a kind of local art.

LS: When did you know you were going to be an artist? Who was helpful in getting your career started?

MS: I had a wonderful teacher at OCA, John Martin, and I used to show him work that I was doing apart from the work that was part of the course we were taking. On one occasion, he told me that there was an exhibition being planned by the Ontario Society of Artists for the Art Gallery of Ontario, and that I should submit two paintings which I had just done—which, of course I never would have thought of. And they were accepted.

When I was in high school, the art teacher was a painter and a friend of all the Group of Seven people, like Lawren Harris. And [through her] I got the art prize. I didn’t even know that I was making art—I made comic strips and stuff like that. But I got the art prize, and on the basis of getting the art prize, I decided that I should study art.

The other influential person shortly after OCA was George Dunning, who was the head of a film company in Toronto. After OCA, I worked for a year in commercial art—and I was really terrible at it. Then I went for almost a year to Europe, hitchhiking around and playing music. When I came back, I had an exhibition at Hart House, of drawings, and I got phone call from this man who had seen the show and liked the work and very much wanted to meet me. So we met, and he told me that he ran an animation company, and that he thought that my drawings showed that I was interested in film—which I wasn’t—and he offered me a job learning how to do animation, which was just absolutely incredible. All of a sudden I was involved in film.

LS: And then you became very well known for film works later on, like Wavelength and La Région Centrale.

MS: Yes, then I became a filmmaker.

On the same subject: Jonas Mekas.

When Joyce Wieland and I moved to New York in ’62, Jonas was very influential in the underground film scene, which we, in Toronto, didn’t know much about. And he was the reason why I sent my film Wavelength to a festival in Belgium. I didn’t know anything about the festival—he told me about it and he urged me to send it. And it won the grand prize, and brought about an amazing change in things.

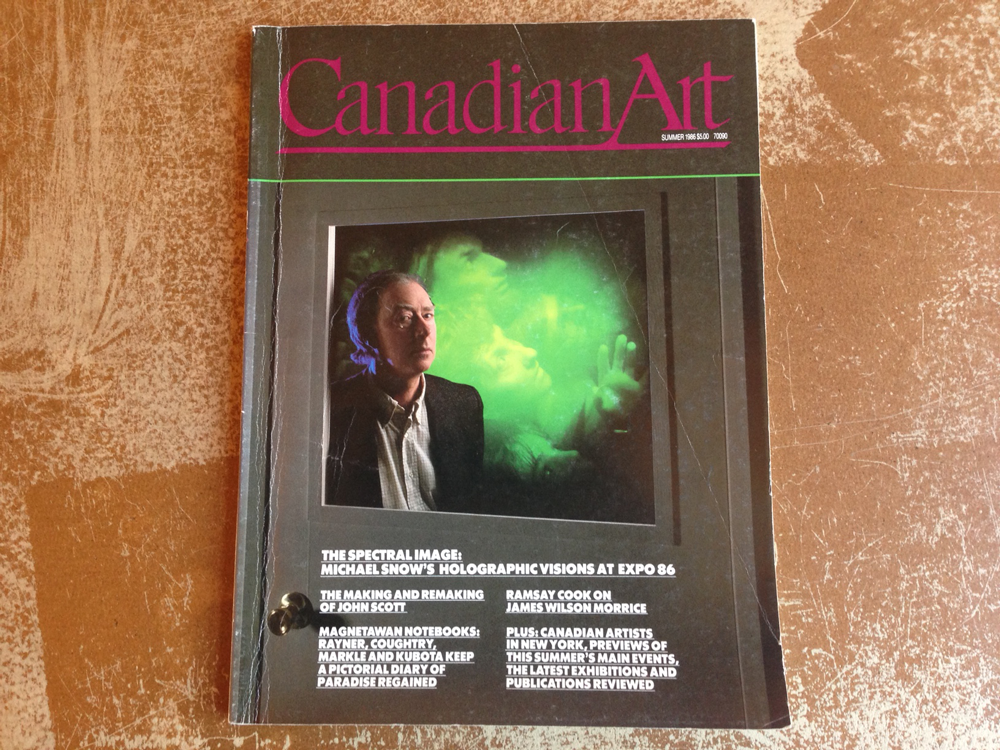

The Summer 1986 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on Michael Snow and the hologram work he created for Expo 86 in Vancouver.

The Summer 1986 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on Michael Snow and the hologram work he created for Expo 86 in Vancouver.

LS: So what would you have done, do you think, if you hadn’t gone into art?

MS: Well, I started to play music in high school, and I continued to play professionally. So that was, right from the beginning, also another career.

At times, I thought I should stop and concentrate on being a visual artist, but I didn’t.

For a while, I was playing with a band, and we were quite busy. We worked pretty much all one year at the Westover Hotel [now Filmores in downtown Toronto]. Around ’59, ’60, something like that. And I had a studio and I made some art that turned out to be interesting at the same time.

LS: And that music practice has continued up to the present day—just a few weeks ago, you played a show at Yonge-Dundas Square. And earlier, you mentioned that the piano in your living room belonged to your mother. Can you tell me a bit more about your first experiences of music?

MS: My mother was a very good pianist. She wasn’t professional, she never played in public, but she could read anything.

Sometimes, when I was in public school, she wanted me to study piano, but I wouldn’t do it. I wouldn’t do anything, actually; I was very obstinate, ridiculous, a serial rebel.

On one occasion, she thought she would go so far as to arrange a meeting with a piano teacher for me, and said she would pick me up at school and take me there. So I told my friends to tell her that they didn’t know where I was.

Then, I discovered jazz on the radio, and I was interested in the piano parts of it—Jelly Roll Morton and Duke Ellington. So I started to teach myself how to play piano, and in a few months I was playing in bands. I met other people who were interested in the same kind of music, and we started to play.

When Joyce and I decided to go to New York, I thought that was a good occasion to stop playing. And I did stop playing at that time, for a while. But during that time, I became more involved in sound in every way.

LS: So when you did give up music for a bit, you focused more on sound in your installations and films.

MS: Yes, sound in the films became a very important thing.

LS: I’m guessing that there is something you get from making music that you don’t get from making art. What is that?

MS: Right from the beginning [in music] it was the improvisation that interested me. Improvisation in jazz is often thematic—there are styles. And I started with that. But eventually it became totally free improvisation.

And I don’t free improvise with any other medium—except, maybe, well I did a lot of drawing starting when I was at OCA and in the next couple of years. They might be improvised.

But basically, with the artworks—sculpture or photographic work—there’s not that much of an improvisation. They are planned. And the same with the films.

So music is, in that sense, a completely different activity and has its particular excitement in that it has never been never played before.

LS: Now, I’m curious about what your favourite albums are—your desert-island discs. What do you think?

MS: One of Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations, which covers so much terrain. There isn’t anything better.

But after that would be some of the Jelly Roll Morton recordings, and his band the Red Hot Peppers, and then more modern jazz—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk.

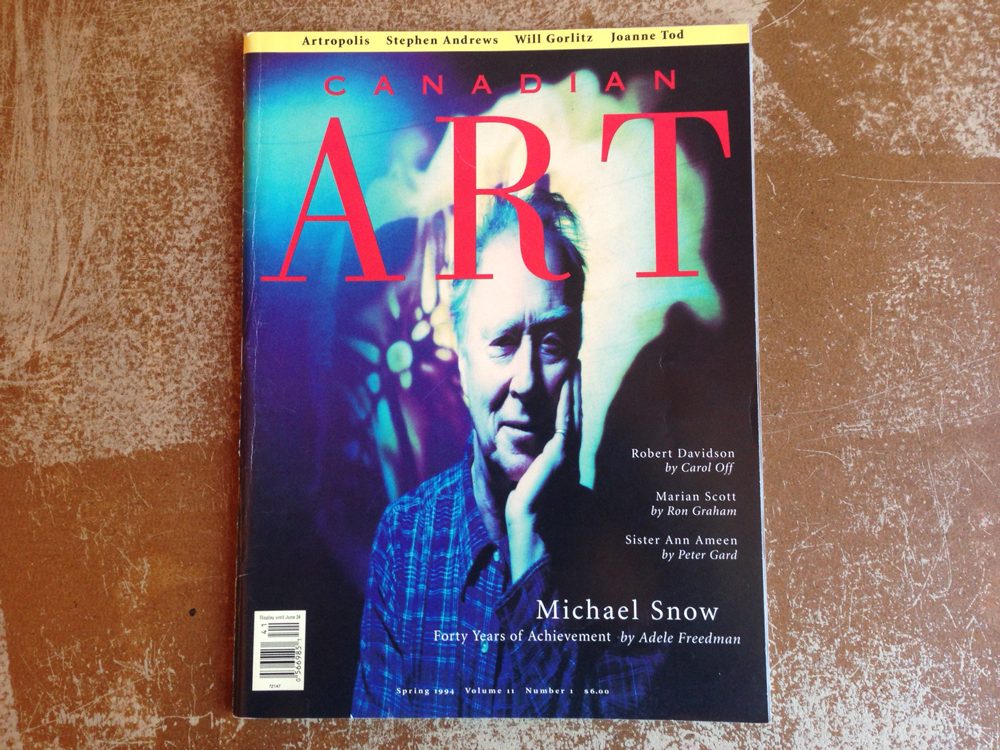

The Spring 1994 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on “Michael Snow: Forty Years of Achievement,” by Adele Freedman.

The Spring 1994 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on “Michael Snow: Forty Years of Achievement,” by Adele Freedman.

LS: You have had such a multifaceted practice, which wasn’t common when you were starting out, but is much more prevalent now. What are the biggest lessons you have learned through all these practices?

MS: Even if you don’t know where you are going, you should go in the direction that is somehow indicated.

You can’t really predict the effect of something, or details of a bigger kind of gesture, and sometimes it takes a little while to learn what you have done.

Watching [a work] and hearing it again, and considering what it is that you did, will sometimes imply what the next thing should be.

LS: Interesting. What examples come to mind?

MS: Well, to make the film La Région Centrale, I conceived of a machine that moved the camera under orders, so to speak. And then I did an installation with that machine. I was surprised to find myself thinking, “this can also do that.”

You know, about two years ago, there was a conference at the Louvre on La Région Centrale—three days of papers by people from all over Europe, and a showing of the film, which is a three-hour film. This was a film that was made in ’69 or ’70, and it’s very much still around.

LS: So what did you learn about La Région Centrale from being at that conference? What did you learn about it anew?

MS: There were very interesting readings of the sound in La Région Centrale, different interpretations of the sound-image relationship.

LS: And while I’m curious about the origin of many of your works, this seems like a good time to ask, where did La Région Centrale develop for you, initially?

MS: What led me to it was the [previous] film called Back and Forth, which is built completely on back-and-forth panning.

The idea for La Région Centrale was that it should be a landscape, and should be completely spherical movements.

La Région Centrale was totally experimental, in the sense that I conceived of the movements, but I’d never ever seen anything like it. When I was shooting, I had a kind of score, but I also improvised.

In one week, it was shot, and we got the film to the lab in Montreal, and next day or so, we went to have a look at it. It was completely new to me. I had never seen anything like it.

It could have been [different]. There was a lot involved, with the helicopter.

LS: You rented a helicopter?

MS: To get there. That was one of the most extreme risks that I’ve taken. Because there could have been something wrong with it—something wrong with the camera, with the helicopter.

Some parts [of the film] were better than others. Mostly, it’s pretty good.

LS: Interesting that you had no clue how it would turn out, initially. What are your favourite films?

MS: It’s hard to say. There are a couple of films by Paul Sharits that I like. And also by Ernie Gehr. And Ken Jacobs, Ron Rice. Stan Brakhage’s The Art of Vision.

Brakhage was very influential in a kind of clarifying way, because I wanted to not do what he was doing.

LS: Why did you not want to do what Stan Brakhage did? Was it your “serial rebel” thing?

MS: Of his work, I thought, he’s a great filmmaker, and, in some ways, too personal and expressionist. I thought that the machine-ness of the camera ought to be stressed, not negated.

What he did was very diaristic, personal—and I think it’s great, what he did, and that was a very avant-garde thing to realize that films don’t have to be made by a crew with a 35mm camera. Stan wasn’t the only person who did that, but that’s what experimental film was founded on—that one person could do it. And Stan was definitely the leader.

Now, Stan hated La Région Centrale. And he didn’t like Wavelength, either. So, in the community of experimental filmmakers, which was small, in New York and San Francisco, [that] was known. He was a great lecturer, and in his lectures he would describe why he thought La Région Centrale was wrong.

LS: What was your reaction to his critique?

MS: I thought it was somewhat understandable considering what he did. What I did wasn’t an attack on him, but it was something that was somewhat opposed, in a sense.

But the wonderful thing about that one day I got a letter, a 20-page handwritten letter from him. He had just seen La Région Centrale and totally changed his mind. “It’s not this, it’s this, it’s this, I see what you meant by this.” And that letter was followed by another letter.

His wife was a Torontonian, and he mentioned that she had persuaded him to give it another chance. And then he changed his mind. Not only did he change his mind, but he really shared what he thought in great depth with me. Wonderful thing to do.

LS: It’s a very generous response. Related to this story: Why has the personal not been of interest to you? Or why do you think you have held off on dealing with the personal in your art?

MS: Well, it might be that the personal style is an aspect of instrumental playing in jazz. Playing jazz is much more personal and stylistic than playing classical music in general.

So it might be that, for me, that kind of personal thing was being taken care of by music. And film as something machine-made started to take on an importance in my thinking.

The Summer 2000 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on Michael Snow in Paris by Bart Testa.

The Summer 2000 issue of Canadian Art, featuring a cover story on Michael Snow in Paris by Bart Testa.

LS: You mention Stan Brakhage’s wife was from Toronto, and I want to ask more about this city. Why did you return to Toronto from New York?

MS: During the time that I was living in New York, it was here, in Toronto, that often I had many shows.

And I guess it was partly political, because Joyce kind of got involved in supporting Pierre Trudeau. And I was in so much in Canada, anyway, that we thought Canada looked interesting.

LS: Your partner was a nationalist, or patriotic, so that was part of the package.

MS: Yes, that’s true.

LS: I’m still intrigued about why you decided to stay here as a base after that time period. What ties you to this place?

MS: Well, my mother is dead now, but she was alive during those years. And the family part of it was actually important—the other aunts and uncles and cousins. Which I don’t see very much, but I still had a connection with them, especially with my mother. So that was one of the reasons.

Mostly just seemed like it would be to be part of something that seemed to have a more creative energy than it had when I left.

LS: So the Toronto scene changed, too, which made it more amenable.

MS: And there was some experimental film. The CFMDC [Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre] was starting, which was modelled on the New York Film-Makers’ Cooperative, one of the things that Jonas did.

Toronto wasn’t a competitor for New York, but it looked like it would be a pleasure to contribute to a kind of new energy.

LS: Where in Toronto did you grow up—what area?

MS: Well, in the first years of my life we moved to Montreal. My father was a civil engineer and the company he was working for asked him to move to work on something in Montreal. And there, he had an accident where he lost one eye, and eventually he became blind.

So there were a couple of years in Montreal, and then when the accident happened, we spent a year in Chicoutimi, which is where my mother came from and where I started school.

Then after that, a year in Winnipeg, which was also related to his work, and then we came back to Toronto, and lived on Belsize Drive, which is near Davisville, and then the rest of the time we lived on Roxborough Drive in Rosedale.

LS: Nice. And was your dad able to continue being an engineer after he lost his sight?

MS: Well, he did some kind of freelancing work. Some guys that had worked for him started their own company, and they had him work on making the bids for possible jobs. So he did have a little bit of work; he learned how to read braille quite fast.

So my sister and I would try to read the plans to him, and he would make notes. He did a little bit of that kind of stuff.

LS: Interesting. I think Sarah Milroy, writing for our website in 2012 about your AGO show that year, mentioned your dad’s loss of vision, and the fact that sometimes people speculate that that’s where your own interest in perception came from.

MS: Obviously, I wasn’t affected as much as he was.

He came to one of the shows that I had at the Isaacs Gallery when it was on Yonge, with his cane. And looked at the paintings like this, [a few inches away from the canvas].

My nickname was brother. Everybody called me “brother,” including my mother.

So this one time, I’ll never forget, he [looked at the painting and] said, “That’s a nice colour, brother.”

LS: So he had some limited vision?

MS: He could see the colour.

LS: That’s a great story. Now, my sense is you always have exhibitions happening these days—that the work continues to circulate in wider spheres. What’s on the go right now?

MS: There is a concert coming up which is two pianos, with Diane Roblin; that’s at Array Space in Toronto in October. Recently we responded to a request from my Paris gallery, Martine Aboucaya, about wanting to make a different installation of a video work of mine called The Viewing of Six New Works. So we spent a couple of hours making revisions and sending that to her. And that particular work, a version of it, is on exhibition right now in Ireland, at the Butler Gallery in Kilkenny. What is very gratifying is that my work continues to have an audience and the audience is growing, in a sense.

Michael Snow will be the honoured guest at the Canadian Art Gala on the evening of September 22 at Andrew Richard Designs in Toronto. For more information, please visit canadianart.ca/gala2016. This interview has been edited and condensed.

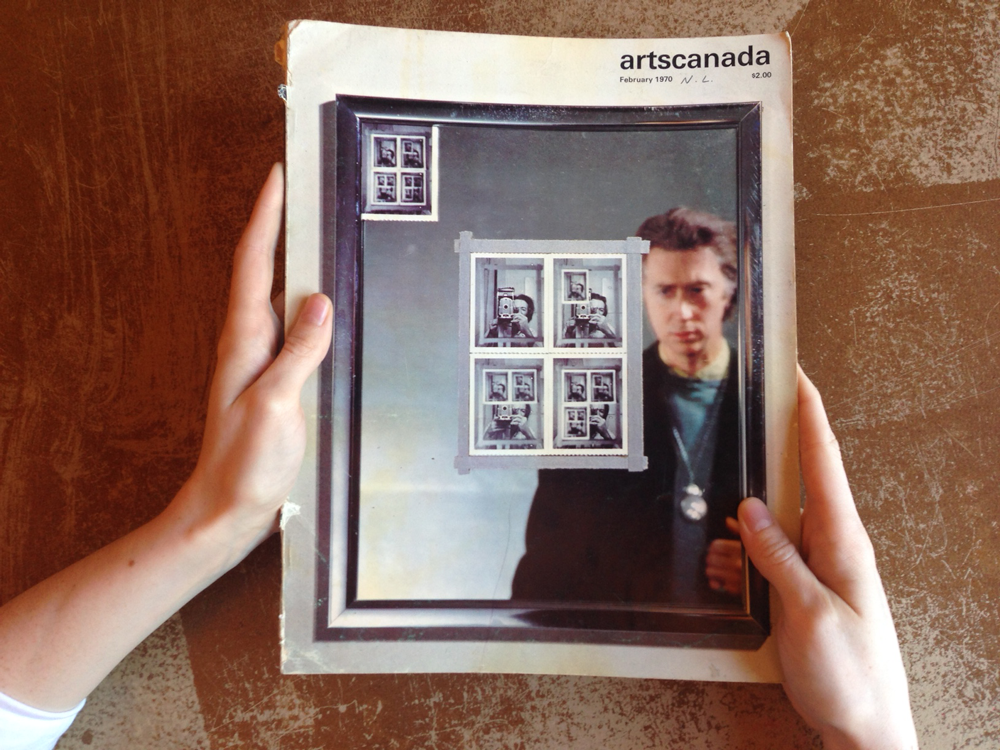

A 1970 copy of artscanada with a cover story on Michael Snow, in recognition of his showing at the Venice Biennale’s Canada Pavilion.

A 1970 copy of artscanada with a cover story on Michael Snow, in recognition of his showing at the Venice Biennale’s Canada Pavilion.