Vancouver artist Howie Tsui has never made anything like Retainers of Anarchy, and you’ve probably never seen anything like it either. Currently at the Vancouver Art Gallery, Retainers of Anarchy is 25 metres long, and five channels—you can barely see all of it from its ends.

Tsui was inspired to create the work based on a spectacular digital projection of a famous Song Dynasty scroll that he saw in Hong Kong in 2010. He was initially struck by the work, but soon realized it could be read as anti-democratic propaganda from mainland China. Ever fascinated by the horrific and the fantastical, Tsui decided to transpose legends from the martial-arts genre wuxia to this grand format—and, ultimately, to do so algorithmically, using multiple, individual sections, so that the video never appears the same way twice.

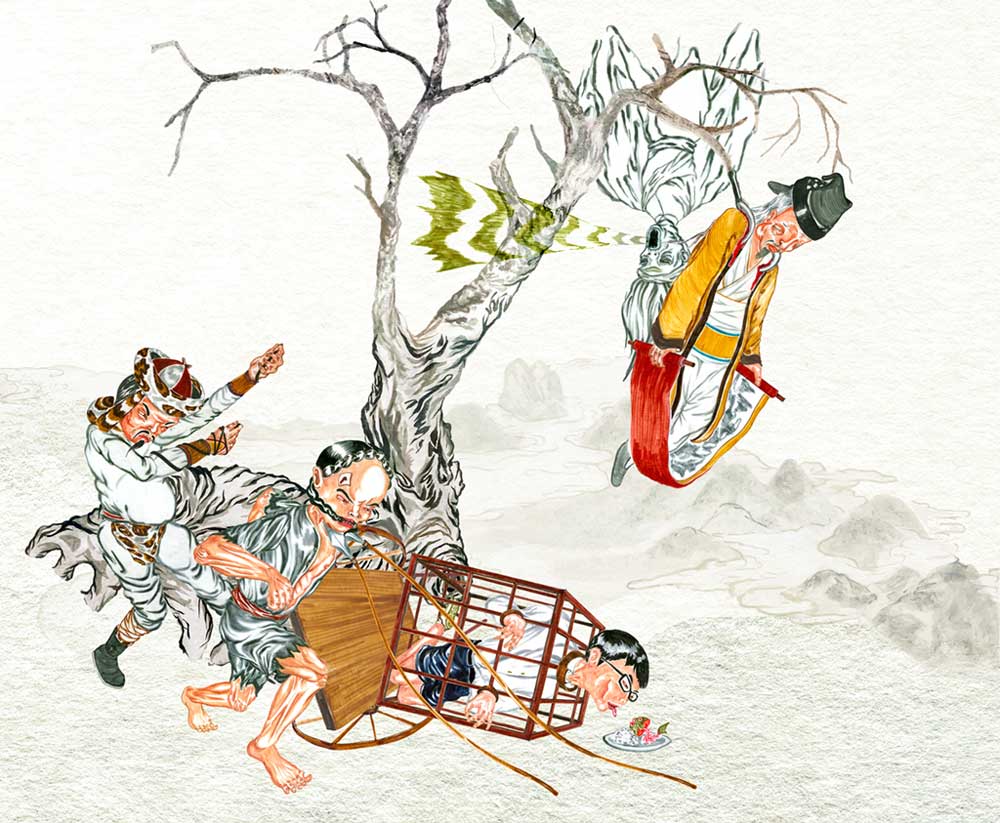

Tsui sets Retainers of Anarchy in Hong Kong’s legendary, and now demolished, Kowloon Walled City, a liminal area of resistance to Chinese authority, and, for almost a century, ungoverned home to sex workers, bohemians, gamblers and any number of outsiders. The vignettes in Tsui’s films are graphic and visceral, typical of the martial-arts genre: baroque dismemberments and fights, which, in the context of wuxia, often involve an underclass kicking against corruption and oppression.

After seeing the show in Vancouver, I spoke with Tsui over the phone in Toronto. He had just returned from a trip to Hong Kong, and with that place fresh in his mind, we discussed the personal and political resonances of Retainers of Anarchy, unpacking its genesis and development.

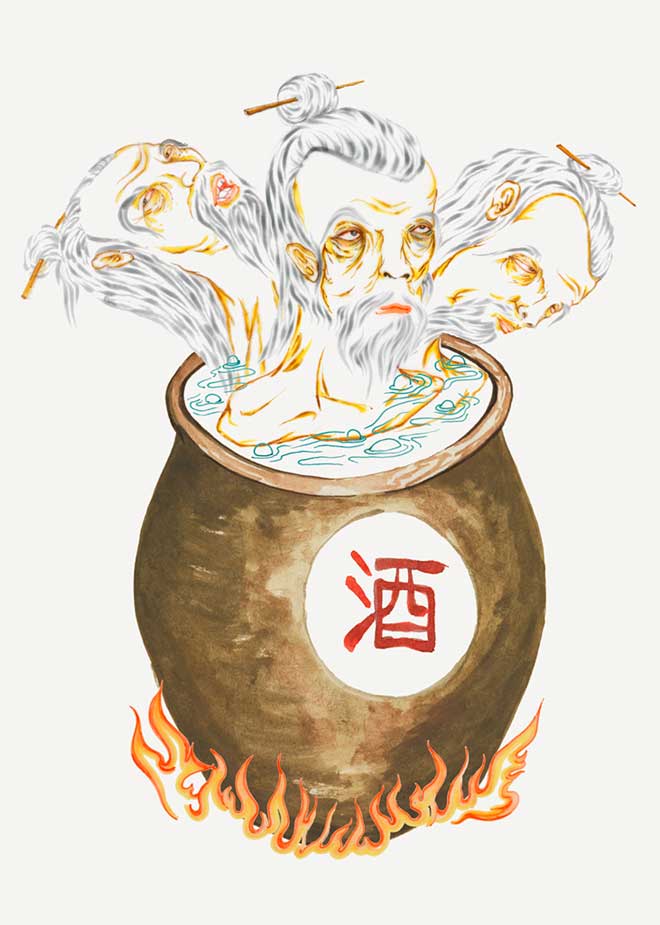

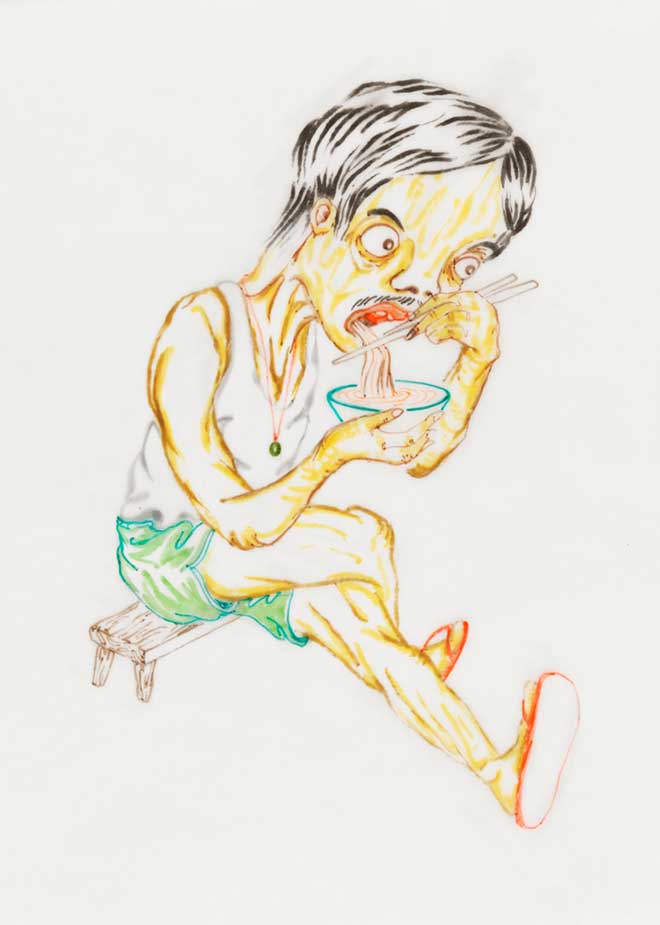

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017, animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4 channel audio. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017, animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4 channel audio. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

David Balzer: The coverage of the show, the didactics, the catalogue, assert your fandom around this genre. This narrative world has been with you for a while. Can you address that—how you encountered this genre, what it has meant to you, how it’s shaped your work as an artist, even your decision to become an artist?

Howie Tsui: I encountered martial-arts fantasy fiction during my formative years as a young kid. Probably five years old. That was when I was living in Lagos, Nigeria. During those early years, from zero to six, I was living in both Lagos and Hong Kong throughout the year. I would watch these shows also in Hong Kong, on TV. And then in Lagos we would receive shipments from my relatives of videocassettes of these TV series. When we were in Africa, they were portals that could transport us back to China. I grew up with [wuxia]. It informed my idea of fantastical, fictive worlds. There’s magic—to see these martial-arts techniques, these figures flying in the air. They provided this space for imagination—to imagine something beyond our world. I think that had a lot to do with my decision to become an artist. I really gravitate towards this idea of creating other worlds through picture-making.

DB: In cultural studies, there’s a lot of talk about how fan culture works to locate and celebrate identities that are marginalized in real life. The fantasy world offers an empowering space that real life can’t. Is this also why you got into wuxia?

HT: As a kid I wouldn’t be reading it that way. It would be more the smoke-and-mirrors elements, the formal, storytelling elements. Looking back on it, I could read it that way—creating a fictive space where I have agency. My intention, though, wasn’t to do that. Getting into this genre came really naturally. I feel like I’m always having to defend why I make the pictures I make, aesthetically. I think I went through a period in art school earlier on where I felt like an outsider, that my picture-making instincts, what I wanted to create, were deemed not-art or low-brow, some sort of idiot-savant stuff. So I did feel like an outsider with the work I naturally, instinctively wanted to make. I spent a lot of years with my practice unpacking my visual language. That’s why I visit these formative cultural things; I’m excavating, doing an autopsy in my brain and figuring out why I have these tendencies. Before martial arts, it was unpacking fantastical ideas from ghost stories, and/or my mom would try to scare me and use modes of fear to protect me, and this sparked my imagination. These horrific, grotesque stories—when you’re a kid you just believe them.

Retainers of Anarchy from Howie Tsui on Vimeo.

DB: The wuxia genre recounts vigilante justice, the toppling of corrupt hierarchies, and also alludes to the history and destruction of the Kowloon Walled City and to concepts of dispossession. Aside from the graphic, blood-splattering nature of this genre, is it also relevant and important to you to highlight its political dimensions?

HT: The project started when I was finishing up the Horror Fables series. I knew martial arts were where I was going next but I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I went back to Hong Kong in 2010, the first time in 25 years, essentially since I moved to Canada. I was there on my honeymoon. We went to see an animated scroll called River of Wisdom, adapted from a traditional Song Dynasty scrollwork, Along the River During the Qingming Festival. It was almost 16 projectors long, just massive.

First I thought, “Oh wow, major spectacle, mind boggled.” But then I started sitting with it and thinking about what it portrayed: an idyllic, socially harmonious city. A deeper political, subtextual reading—this was a mainland China–produced spectacle in 2010, which then travelled to Hong Kong. And then I started to read it as some soft power messaging about how wonderful our city or society could be. Like, “this is traditional China; keep the harmony”—especially at a time when Hong Kong was in turmoil, and in a position of being dispossessed.

That’s when I developed a political intent. We’re seven years away from that now. When I did research into this martial-arts genre and the author Jin Yong, I didn’t know it was a censored form of fiction in mainland China. That was crazy for me, because it was the most accessible thing I grew up with. But this author ended up moving to Hong Kong as a safe space. Once I read about that I started to look at his narrative and stories differently—there was a subtext in the stories that encouraged dissent and resistance against authoritative bodies. So that’s where everything started on a political level. I wanted to use martial artists as avatars for current political resistance figures, and vice-versa. Or conflate martial-arts figures with regular people who lived in the Walled City, these self-organized societies.

DB: I guess there’s also that feeling of anyone who is part of a diaspora, where you’re encountering something that should technically be your own, but it’s also new to you, so it’s a kind of diasporic reappropriation—of something that is somehow part of you but that you forgot, or maybe never knew. Was taking this on a way to force yourself to become more intimately connected with the history of Hong Kong, and/or yourself?

HT: In the stereotypical diasporic-Canadian experience, you move here, assimilate and then become “Canadian.” The martial arts television series were portals or satellites to keep us tethered to our origins. But it’s super-constructed; it’s not real. You reach a certain age when you’re an adult and think that you spent so much of your young life trying to erase your own culture. And then you reach a point where you find it’s a part of you, and you can’t erase it; you need to balance it out. You want to learn more. This happened for me in university. I always wanted to take Asian cultural-studies classes, but they always conflicted with other courses I had to take, so I never ended up taking them. In a way these projects are the result of me missing out on these basic Asian cultural-studies courses I couldn’t take. It’s self-directed learning.

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

DB: How did you manage to execute this on such a grand scale? This feels like a major step forward for you. And institutionally, it’s so elegantly and epically presented. What was the journey to getting to this point: the mechanics, who helped you, etc.?

HT: It began with the idea, but then I wasn’t very sure how I could do it. Basically the major lynchpin, the wizard-magician-collaborator I worked with on this is media artist, composer and genius-kid Remy Siu. He was part of this performance collective called Hong Kong Exile. Around 2014–15 there was a quick-and-dirty performance collaboration I did with those guys at Centre A called Cantosphere. I had just come back from Hong Kong in 2014, from an exhibition I had there, and that was the exact same time that the Umbrella Revolution was happening.

This collective wanted to conflate the precarious nature of Hong Kong sovereignty with the erasure of Vancouver’s Chinatown. I was more of a thinker there but wanted to focus on the importance of Cantonese as a language, which is something that’s being erased from Chinatown. That’s where I met Remy. After that project was over, I told him I was working on this project, and showed him videos of the River of Wisdom animated scroll, and asked him if there was a way we could do that. He thought so, but it was all speculative. So I had five animators: four Emily Carr animation students and one alumnus. I consulted with an animation professor at Emily Carr who would bring me names of people I could work with. The production line was essentially: me making the original works, creating the key frames for animation, and forwarding them to the animators, who rendered them into video files.

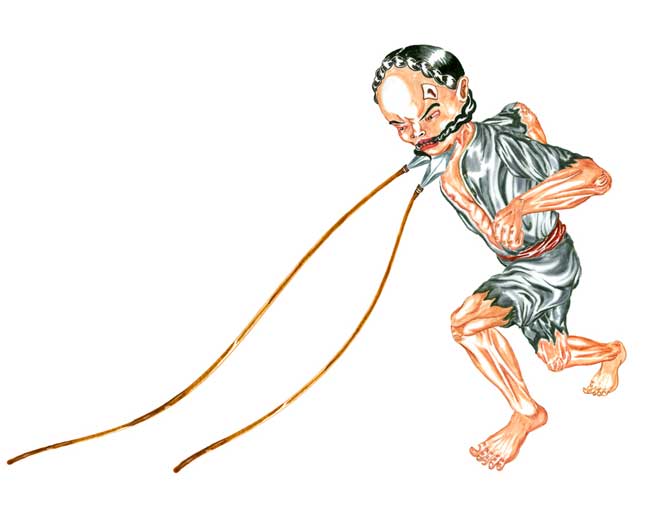

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

DB: Were the bookending works at the VAG—the video collage and the sculpture—intended to accompany the projection, or added on?

HT: In the earliest proposals they were both there. About three years ago I had the idea for the sculpture. The video I didn’t think I’d have time to do, but the VAG A/V department helped me out. Originally I wanted to make a weird bunker for the video collage, a recreation of my basement in Thunder Bay. The way we immigrated here was that my dad was part of a business-immigration initiative; he was going to be an entrepreneur, and his business was producing videocassettes in Thunder Bay—blank tapes. So the symbol of the tape is very important to my family, and for this work, because all the material comes from videocassettes.

I can’t read any Chinese, which is probably good for me because I don’t consume information as well through reading. When I talked with someone about this project they asked if I had read the series; apparently it’s much longer, more developed, the characters’ backstories are much deeper. But I can’t read Chinese! In a way it’s just a reflection of my situation, of switching over to English and not keeping up with my Chinese, dropping out of Chinese weekend schools in Thunder Bay.

DB: So we’re back to the beginning—you have a sense of mediation with this world as well.

HT: I’m rarely ever happy with anything I do, but when I look at this I’m not nitpicking or bitching. I’ve been away from Vancouver for about three weeks, and I just did a talk at the gallery, and the work still feels like me, but in a way it’s like, to use a metaphor, you had a kid and it goes to university. You’ve nurtured it up to a point. And now it’s on its own.

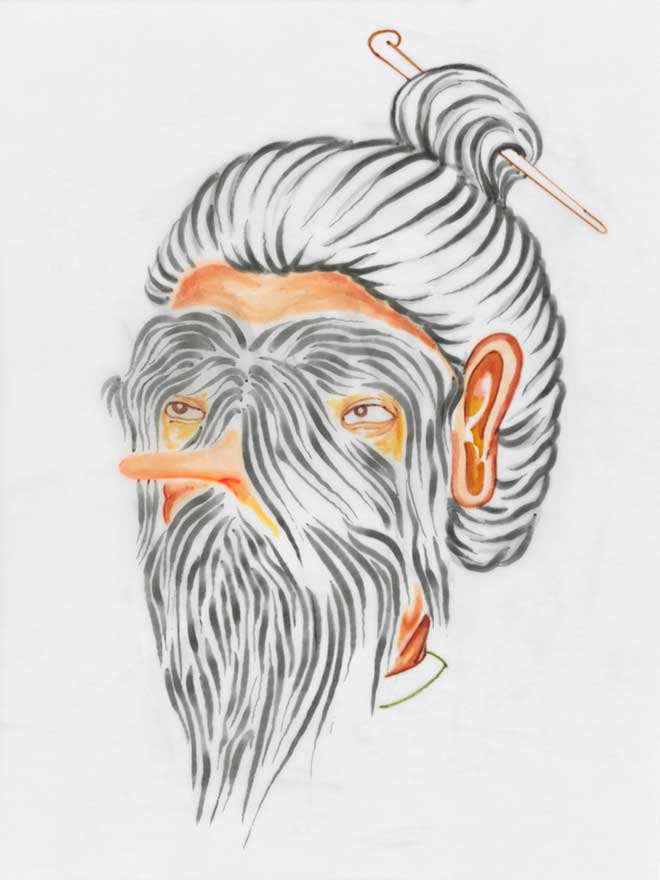

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Howie Tsui, Retainers of Anarchy, 2017. Animation key frame drawing, 5-channel HD video installation, 4-channel audio. Photo: Maegan Hill-Carroll, Vancouver Art Gallery.