This spring, Julie Crooks, assistant curator of photography at the Art Gallery of Ontario, put together “Free Black North,” an exhibition of photographs of Black Ontarians dating back to the mid-19th century. At a related public talk, Crooks, along with interdisciplinary artist Deanna Bowen, poet and scholar Afua Cooper and dance artist and scholar Seika Boye, described a recurring challenge of doing archival research on Black life in Canada. Three of the four women shared similar experiences of being turned away by librarians, archivists and other gatekeepers of historical artifacts, who patiently explained that the materials they sought did not exist. After some persistence, each woman found that this was in fact not true: they exist, in dusty boxes, public-record offices and library storerooms. An assortment of documents hidden in plain sight holds traces of Black Canadian history.

In the circuit of museums, galleries and artist-run centres in Canada, Black women curators like Crooks are rare. Not much has been written about them. One reason is that Black women are simply not hired. Two online studies commissioned by this publication lay a delicate statistical assault on any lingering art-world myth of professional meritocracy. In 2015, Canadian Art found that, overall, the representation of white men in solo gallery shows was disproportionately high. Two years later, a study of directorial and curatorial positions determined that “visible-minority and Indigenous gallery administrative staff is severely underrepresented” and that “gallery management is whiter than Canadian artists in particular, and the Canadian public in general.” Our national art community is structurally calibrated to privilege white men, making the remembering of the contributions of Black women in the field even more crucial.

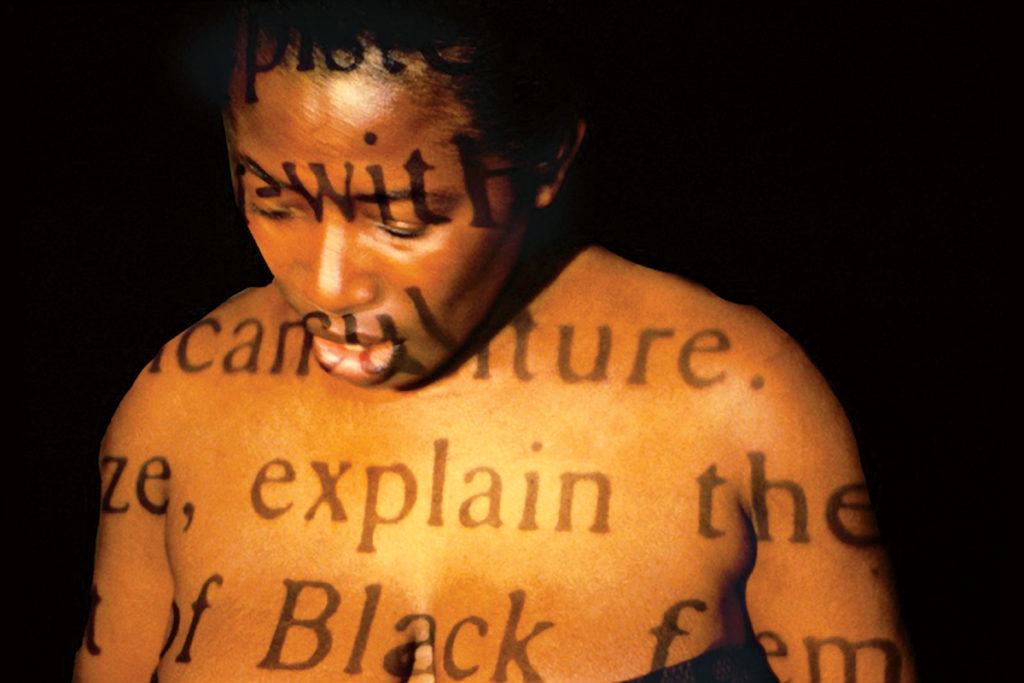

Jérôme Havre, Six Degrees of Separation, 2013. Textile, cotton, iron wire, copper, ink-jet prints, sound track, acrylic and chalk, dimensions variable. Courtesy Thames Art Gallery. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

Jérôme Havre, Six Degrees of Separation, 2013. Textile, cotton, iron wire, copper, ink-jet prints, sound track, acrylic and chalk, dimensions variable. Courtesy Thames Art Gallery. Photo: Frank Piccolo.

According to art historian Alice Ming Wai Jim, the 1989 travelling exhibition “Black Wimmin: When and Where We Enter” was the first Canadian exhibition to be curated by, and to feature, Black women artists. Organized by Buseje Bailey and Grace Channer, the show toured museums, galleries and artist-run centres across the country.

“Bringing forward issues of historicity and spatiality,” Jim wrote in a 2004 essay, “the exhibition presented itself as a challenge to dominant, traditional Eurocentric politics of aesthetics and representation and its various undercurrents existing in the Canadian art arena, which, in its denial of difference in the name of multiculturalist liberalism, habitually ignored the contributions of artists of colour.” Jim describes how the works dealt explicitly with Black Canadian experiences, as well as issues of representation and resistance. These same concerns have reemerged in many of the exhibitions organized by Black women curators since.

Pamela Edmonds, now curator at Thames Art Gallery in Chatham, Ontario, has been curating since the late 1990s. Edmonds describes being influenced by Bailey’s work as an artist, organizer and curator. While in her early 30s in Halifax, she began approaching galleries and artist-run centres to curate exhibitions that would counter the lack of representation of Black artists in her community. “At the time there weren’t a lot of curators, so to speak, who would call themselves curators,” she says. “It was at the very beginning stages of professional curatorial practice. There weren’t any degree programs then.” Edmonds learned to balance the interests of the artists and the institutions, and eventually developed a subversive approach to the latter’s diversity mandates.

“I felt at the time a sort of resistance, in a broad sense, to what a curator does,” says Edmonds. “It was seen as a position that was going to restrict the artist. I was very cognizant of this, of trying to not be someone who was positioning myself within a hierarchical relationship.” As a result, Edmonds learned to negotiate multiple perspectives in her curatorial practice. “A curator is a facilitator between the institution and the artist and the public. As a woman of colour, I think we are used to doing that, to always negotiating and interpreting these voices [and interests].”

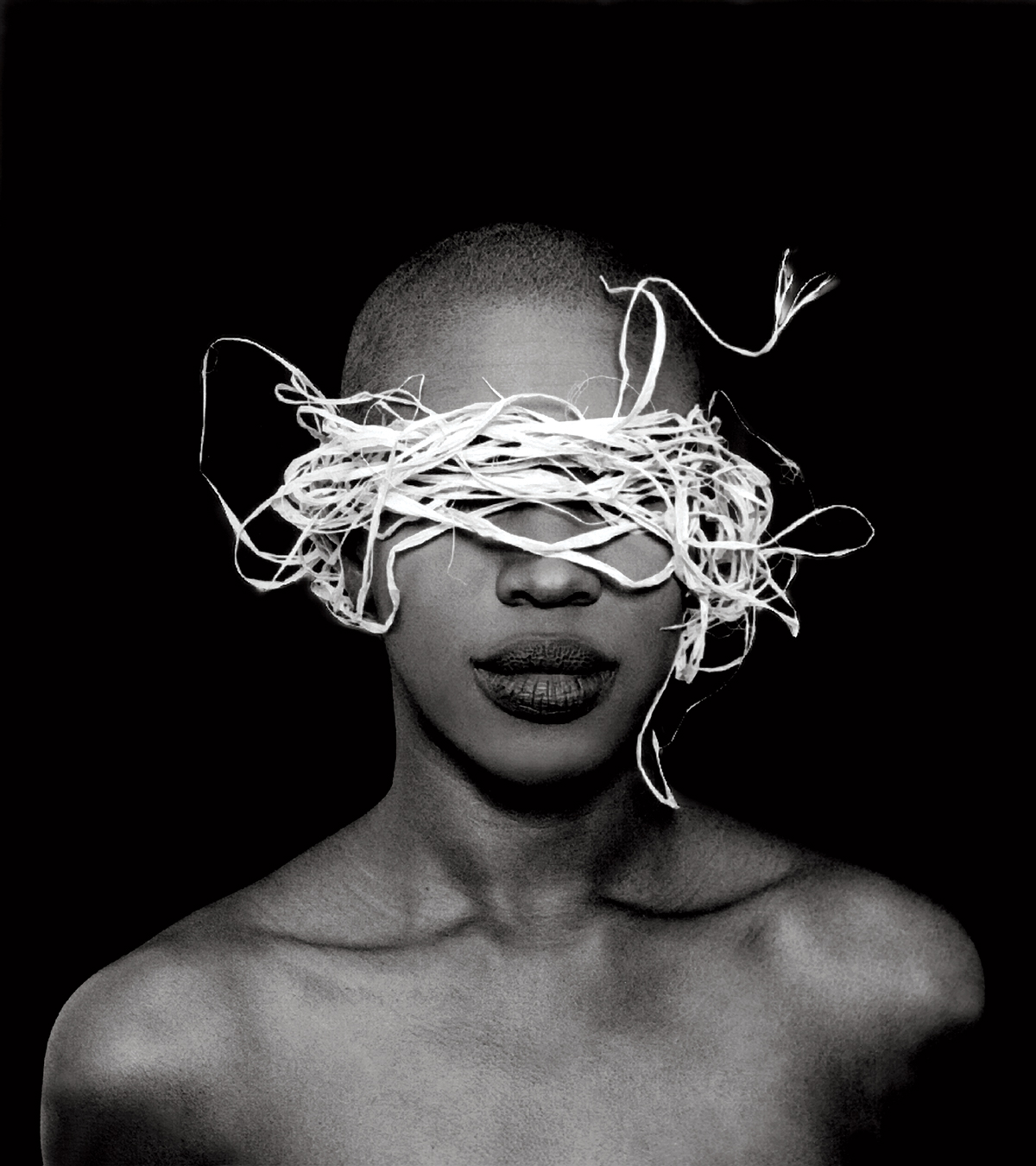

Michael Chambers, Blinders, 1994. Silver gelatin print, 81 x 71.1 cm.

Michael Chambers, Blinders, 1994. Silver gelatin print, 81 x 71.1 cm.

Even if it hasn’t always been strictly in a curatorial role, Black women in Canada have organized and presented many exhibitions since “Black Wimmin.” In 1997, Bailey returned to her initial curatorial premise with “Women’s Work: Black Women in the Visual Arts” at YYZ Artists’ Outlet in Toronto. In 2000, Edmonds worked with the Sister Visions collective to organize “Through Our Eyes” at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax. The show’s significance to the local Black community was exemplified in a collaborative piece made of found materials from what was once Africville, which claimed space in an institution that had existed for more than 150 years without ever hosting an exhibition by Black contemporary artists.

Edmonds later curated “Black Body: Race, Resistance, Response” at the Dalhousie Art Gallery in Halifax in 2001. Meanwhile, Gaëtane Verna curated “Epistrophe: wall paintings” by Denyse Thomasos in 2004 at the Foreman Art Gallery of Bishop’s University in Sherbrooke, Quebec. In 2017, “We are the Griots” was curated by Jade Byard Peek at the Anna Leonowens Gallery in Halifax.

Over time, the thematic focus of these curators’ exhibitions has expanded beyond representation to include considerations of how colonialism, imperialism and capitalism affect us all in unique ways. In 2007, curator and researcher Andrea Fatona collaborated with Bowen to curate the touring group exhibition “Reading the Images: Poetics of the Black Diaspora,” in which several artists created new visual vocabularies to explore the Canadian nation state’s relationships to Black diasporas.

In 2014, Fatona and Katherine Dennis curated the “Land Marks” exhibition, which toured to three galleries in southern Ontario. “In Another Place, And Here,” curated by Michelle Jacques and Toby Lawrence in 2015 at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, asked Black, Indigenous, white and POC artists to closely examine the relationship between where they lived and worked, emphasizing intersections of identity and place.

Dawit L. Petros, Barella and Landscape, No. 3, Osbourne, Kansas, 2012. Archival digital print, 76.2 x 101.6 cm.

Dawit L. Petros, Barella and Landscape, No. 3, Osbourne, Kansas, 2012. Archival digital print, 76.2 x 101.6 cm.

Political trends in the art world have shifted in recent years from identity and representation to diversity and inclusion. Eunice Bélidor, emerging curator and programming coordinator at Articule Gallery in Montreal, is a part of a younger generation of Black women curators for whom the Internet has served as a vehicle for research and social exploration. Bélidor describes a general self-awareness among her colleagues and peers that things aren’t quite right—that marginalized people are often the ones who end up doing the extra work of outreach and systemic adjustment.

Everyone can and should be doing this work, Bélidor argues: “You don’t have to be a person of colour to understand people-of-colour issues,” she says, “or to want to bring their perspectives into your centres.” Regarding inclusion, Bélidor suggests: “You don’t have to only have one of them, and you also need to make sure that’s its not just POC visual representation: you have to include them in your internal structure as well.”

The continued work of Black women curators in Canada shapes a distinct conversation responsive to settler-colonial histories and the unique experiences of the Black diaspora. Black curators, scholars, critics and artists are getting together more frequently, learning about each other’s practices, and creating projects for the future. Fatona’s 2014 conference at OCAD University, The State of Blackness: From Production to Presentation, was one such major event. In 2015, curators Verna, Edmonds, Fatona and Crooks joined curators Dominique Fontaine, Sally Frater, artist Camille Turner and critic and scholar Rinaldo Walcott to attend the 56th Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor, as a Canadian delegation.

Trips such as this, part of the continued organizing of Black women curators, make their work known abroad, while allowing them to continue their important contributions at home. Bélidor puts it best: “I really want to just see Black subjects or subjects of colour being repeatedly in the programming. Not because we have to have one each year, but because they actually do great stuff.”

This post is adapted from an article in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art.