Taylor, I’ve returned to bell hooks’s essay “Being the Subject of Art” from Art on My Mind. I want to spend time with her notion of transgression. There is translation, or the refusal of such, and there is also transgression. hooks writes: “To transgress I must move past boundaries, I must push against to go forward. Nothing changes in the world if no one is willing to make this movement.” We have not yet lived a long, full life, but I am beginning to understand more deeply what it means to transgress. When I say this, what I mean is that we are learning what it means to cross boundaries.

Through our work we find ourselves in the centre of art worlds that do not always know how to care for blackness. At times, I have entered into a gallery or a museum or some non-profit organization and have made myself small. I immediately think: this does not feel right. I should not have to shrink in order to be here.

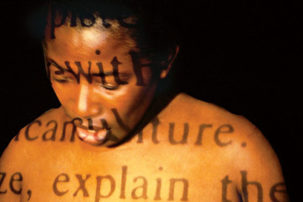

When I returned to this essay by hooks (it has been a decade since I last read it) I was reminded that when we cross boundaries, we also declare new relationships to our bodies. That as critics and curators and art workers, we navigate Du Bois’s double consciousness and that negotiation—personal and political—is also physical.

The exhaustion of “otherness” lives on our bodies.

In our line of work, the assumption is that there is something transcendent about Art. Perhaps there is truth in this. And yet, it feels imperative to question why it often feels that the environments in which we have laboured—what we do to pay our bills—do not have the capacity to really take care of us. So when hooks says that to transgress we must return to the body, I say to myself that I must be deliberate not only in how I show up, but where I show up.

You recently shared with me a movement score for pleasure and gratitude. When I enact it, I am charged with calling to mind that which brings me pleasure. This is done through a keen attention to my body.

Feel the weight of your body standing on the ground.

On this earth.

Let all of your weight sink into the ground.

Feel the gravity in your body.

Let it fall.

Since receiving this from you, I have begun every morning this way in my own attempt to articulate what is coming next for me. This feels like a transgression. I want my work, as someone who grapples with the tensions of cultural production, to be a practice imbued with pleasure and gratitude. Even if it is hard. Even if there are times when my fatigue and disappointment and anger seek to resist this effort. I want my work to be embodied with a deep, deep sense of joy. I want my body to be well, to not be made to feel small. I want to cross a new threshold and to do that, it means I will leave the sites in which I cannot be well, in which I cannot be whole.

I am firm in this declaration.

Jessica, I recently read “Art Won’t Save Us” by Anna Khachiyan who explains, “as long as art remains a prestige economy of the free market—a glitzy barnacle on the side of global finance—it cannot be an effective tool for political change.” I am no nihilist, but I share this sentiment. I cannot expect for an industry that has traditions of colonialist preservation to care for me—a Black queer woman. I was naive to ever think so. Khachiyan solidifies the paradox that is the art world: an industry that wants to be transgressive through art while capitalizing on such transgressions.

Your focus, though, on the subjective/embodied transgression is more hopeful. As we cross boundaries and engage with the histories and contemporaneity of the art industry we must consider the ontological implications of race, gender and sexuality within an art institution.

This afternoon a friend sent me this text: Having one of those days where the whiteness is overwhelming and I feel unseen, unheard and just like…‘what the fuck am I doing here.’ My friend works at an art institution. And though she did not inform me of any specific situation that prompted this testimony, I knew exactly what she was feeling and what caused it. Because I have felt this way too. In these moments, I urgently try to facilitate care for my friend as if I am in triage. (There is a certain protocol that I have become familiar with in these cases.) I know what to do, because other Black women working in institutions have done it for me.

I know exactly how you feel. What do you need? Do you need to talk? Want to get away for lunch? I will check on you later.

I have been consulting with the universe lately. As I traverse boundaries, I have relied on the power of intuition and the interconnectedness of our world(s). This requires a certain slowing down, and a praxis of being present. For some reason or another this notion of pleasure keeps finding its way to me—quite serendipitously—in a book of theory, through a friend, in a therapy session. Pleasure, and not just sexual pleasure, but all types of pleasure, has been top of mind. The score that I sent to you came out of this rumination on pleasure and the act of being present. My dear friend and artist Jennifer Harge utilizes the score as a way to identify and locate pleasure within our own bodies. The score is often a somatic activity. It is the ultimate form of embodiment.

While doing this activity, I have realized how foreign this act is to my body and consciousness. I innately resist it: who am I to prioritize pleasure? There is work to be done… After which I realize this is the work. For me, my commitment to prioritizing pleasure is not just a practice, but an act of resistance. It is revolutionary.

I’ve found pleasure in understanding that I am not alone. There is a collective of us transgressing day to day, while simultaneously and unapologetically prioritizing pleasure. To code-switch like this is no small feat. Oh, but could you imagine a world where we could be our whole selves any and everywhere? Where we wouldn’t have to make ourselves small for the sake of anyone?

Taylor, you are right to acknowledge that transgressions can be collective movements. We do not have to be alone as we find or build or imagine new worlds. Care, then, is a strategy. I don’t say this to imply that loving one another must be an overly analytical act; it too must be steeped in imagination. However, care must be deliberate. We must set our intentions and act on them.

Here, in New York, I am watching Black women refuse the act of simple translation in service of intentional illegibility as care. That is, we are refusing to bare ourselves, burn ourselves out, in service of that which does not serve us. I want to propose then, after considering what I have written earlier, that the refusal to translate is in fact transgression. I want to propose then that to transgress is also to love; it is an embodied love steeped in rigour and pleasure and imagination.

I am reminded of these words from adrienne maree brown: “We are each other’s medicine.”

Jessica, this week has been a tough one for me at work. As I always do, I leaned on my close ones. They provided medicine for me. I got up this morning with a new outlook, but still exhausted. I practice grace when faced with institutional microaggressions and toxicity, as we both know the optics of a white woman’s madness and distress are more acceptable than those of a Black woman’s. But I am also reminded of Audre Lorde’s call to break silence:

I was going to die, if not sooner then later, whether or not I had ever spoken myself. My silences had not protected me. Your silence will not protect you. But for every real word spoken, for every attempt I had ever made to speak those truths for which I am still seeking, I had made contact with other women while we examined the words to fit a world in which we all believed, bridging our differences. And it was the concern and caring of all those women which gave me strength and enabled me to scrutinize the essentials of my living.

I consider the collective, the other Black women who are experiencing microaggressions in institutions, those who probably feel alone. I want to assert labour toward encouraging care for one another as we matriculate through these spaces, or even out of them.

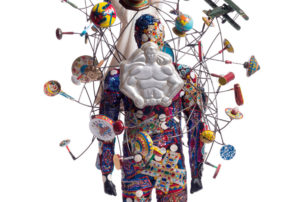

Last night, I saw Jennifer Harge’s latest performance—which was carried out by her dance company Harge Dance Stories—titled FEDS WATCHING (2018). The piece presented a series of body movements performed by four Black women dancers who explored methods of subverting surveillance within a Black femme embodiment. The piece incorporated elements of clandestine ritual, metaphors of endurance and the glitching of movement that transpires as one commits to persistent acts of survival, even when everything else around desires to destroy them. Ultimately, the piece emboldened us to break silence, disregard the watchers and commit to a future way of living that does not require the shrinking of the body to appease or make comfortable the privileged onlookers.

I found pleasure in exploring this type of imagination.