My introduction to Aruna D’Souza’s work was through her incisive posts calling out Dana Schutz in a Facebook group for BIPOC in the art world that she founded. There and on her personal page, D’Souza’s posts were at the forefront of rapid-fire discussion around the 2017 Whitney Biennial controversy, the centre of which was the white artist Dana Schutz’s depiction of lynched Black teen Emmet Till’s open casket. To top it off, D’Souza had been consulting for the Whitney’s education department in 2016 and 2017, conducting a monthly reading seminar to discuss questions of racial diversity and inclusion, and creating strategies for the Whitney to engage audiences of colour.

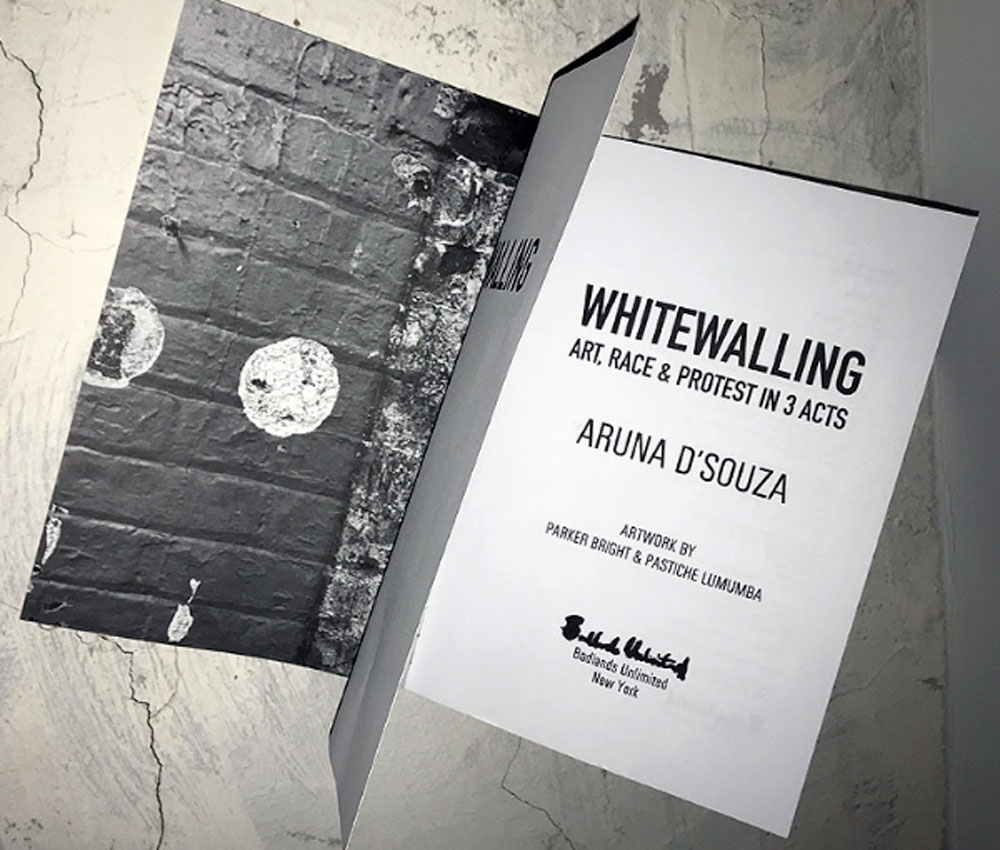

D’Souza’s new book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts takes the IRL and URL protests against and in defense of Schutz as the starting point for two historical precedents that also expose the white privilege of the defense of free speech at the expense—and dismissal—of Black pain and protest, and the limitations and hypocrisies of the critical and institutional responses to these protests. The second example in the three-part book is “The Nigger Drawings,” a 1979 exhibition by a white artist, and the third one is a 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called “Harlem on My Mind” that didn’t feature a single Black artist.

By drawing uncanny similarities between the culture wars that erupted in response to each, D’Souza reveals that the art world hasn’t progressed as much as we like to say it has. Whitewalling issues an urgent call to action for allies and for institutions, especially following a concentrated year of art-world controversies—think Jimmie Durham, Sam Durant, Joseph Boyden, and on and on—that brought to the fore many unsettled questions: Can white artists depict the stories of marginalized peoples? What comes after the call-out? What are the responsibilities of so-called, self-declared allies towards marginalized peoples? How can the institutions in question move past panicked, disingenuous apologies and towards sustained and sustainable systemic change?

These questions echo throughout D’Souza’s critical writing practice and social-media presence. Before turning to writing about contemporary art, race, intersectional feminisms and politics only a year and a half ago, D’Souza was a long-time 19th-century art historian. Her frustration with the limitations of academic writing made her quit academia six years ago.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s seminal essay “The Case for Reparations” informed the ethos of her foray back into art writing. “I started to think about what a reparative model of art criticism would be for me, and I decided that my reparative gesture would be [through] attention,” she told me, and for D’Souza, that involves asking herself: “Who does my writing serve? Is it useful to the people I feel have been left out of many conversations? For me, a lot of what the book is about is the question of how to be an ally and how that has broken down in these various situations. It’s an exercise for me as a non-Black writer of colour: How can I write about Black protest? And what’s my role to centre the arguments of Black artists?”

D’Souza was born in Edmonton, raised in Flin Flon and Lethbridge, and is now based in Williamstown. Her reviews have covered work by Black artists like Latoya Ruby Frazier, Kara Walker, Toyin Ojih Odutola, and many others, and much of her analysis calls out art-world anti-blackness, in publications such as MOMUS, CNN and at 4Columns, where she’s an editorial advisory board member. D’Souza also writes a food blog called Kitchen Flânerie, and she’s editing a forthcoming anthology of her long-time mentor and friend Linda Nochlin’s writing.

As part of the Canadian Art Encounters series, I will be in conversation with D’Souza on May 10, after a reading. She will also sign books, which will be available for purchase on-site from Art Metropole. Tickets are available now.

An Excerpt from Aruna D’Souza’s Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts:

When I set out in the summer of 2017 to write a book about art, race, and protest, there was already more than enough to grapple with. Major controversies had erupted during the previous ten months, spilling over from the relatively small and bounded space of the “art world” (an already amorphous network of artists, critics, art historians, gallerists, museum types, and other interested parties) into a set of much larger conversations in the porous space of social media. In September 2016, residents had expressed anger at an exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis—just miles from the site of the Ferguson protests two years prior—of Kelley Walker’s work, which deploys images of black bodies in equivocal, even outright abject, ways. The following May, Sam Durant’s Scaffold, a large outdoor structure that included representations of the gallows used to hang thirty-eight Dakota men in 1862, on which visitors to the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis could climb, was accused by Native activists of trivializing the largest mass execution in US history and a signal event in the long process of US genocide of indigenous populations. In June, long-standing challenges by Native art historians’ and artists’ to the artist Jimmie Durham’s claims of Cherokee heritage gained traction as a major retrospective of his work traveled to the embattled Walker. In September, animal-rights activists started a petition that has by now garnered over eight hundred thousand signatures, demanding that the Guggenheim remove works that were deemed abusive to animals from their upcoming survey of Chinese contemporary art. Even as I was writing the final words of this book in December 2017, amid the intensity of the #MeToo movement targeting sexual abusers and in the wake of revelations that Roy Moore, a GOP candidate in the Alabama Senate race, had sexually abused a number of young girls, a petition circulated asking the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to reconsider their display of a notorious painting by the French artist Balthus that thematizes pedophiliac desire.

And, of course, there was the controversy to end all controversies, the decision of the curators of the 2017 Whitney Biennial, one of the most-watched events in the US art world, to include a painting by the white artist Dana Schutz depicting the brutally lynched body of the young Emmett Till in his coffin.

There was no end of examples to include. But even more urgently, the issues being raised in the debates around each of these cases were entwined in a much larger set of conversations—although conversations seems like too polite a term—about some of the most fundamental pieties and values of liberal thought. How to discuss questions of cultural appropriation (in other words, the questions of what histories to engage, how to engage them, and who is best to engage them) and of free speech, without also talking about whether Milo Yiannopoulos or Richard Spencer, notorious white supremacists, should be allowed to speak on college campuses; or whether the mass-produced statues of Confederate “heroes” installed during the Jim Crow era in the South should now, finally, be taken down? How to think about these issues without also thinking about contemporary violence being visited on black and brown bodies, the possibilities and limits of protest, and whether it’s okay to punch a Nazi? How to approach the question of what art institutions hang on their walls without asking about the responsibilities of institutions—all manner of institutions—to make space for everyone, or at least to be honest about whom they are built to serve? How to talk about any of these cases without seeing them as manifestations of the activism around Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, and #MeToo?

To complicate matters further, the form of many of these protests vastly exceeded any physical gathering of people—they were happening through Facebook debates, Instagram posts, Twitter flame wars, viral memes, and articles with inflammatory titles that often went unread in their entirety, and so on. It has become easy for people to lament the degradation of discourse due to social media, especially in the wake of the 2016 US presidential election, when we discovered how fake news could be taken for real and how algorithms could generate outrage and unwavering belief by turns. And to be sure, social media’s usefulness as a space of protest is fraught—encouraging “clicktivism” and easily expressed solidarity or condemnation that need never be tested in one’s off-line interactions. But it is also a space in which thoughts first become visible, in which people who might never otherwise have the opportunity or interest in forming an opinion on a given topic—especially on questions of art’s place in political discourse—are encouraged to do so, if only because all those social media platforms coerce us to participate by their very structure. I have no doubt that for the vast majority of people who weighed in on any one of these controversies, it was the first time they had ever expressed a judgment about what art should be able to do or say. That itself seems like something to think about further.

But while everything about these various art-centric protests seems perfectly keyed to our moment—to the present—none of this is new. What many are calling our new culture war is imagined to be a reiteration of those that came before—the outrage stirred up by then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani against Chris Ofili’s painting The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) when it was shown at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999, or the early 1990s attack by right-wing politicians like Jesse Helms against the “immoral” art being supported by the National Endowment for the Arts—with the same whiffs of a reactionary and stifling puritanism that went along with both.

But to see our current culture war as a mere repetition of previous ones is to misrecognize how they are alike and how they are emphatically different. What all of these events do have in common is that they were moments of reckoning. Institutions of public culture were being forced to rethink how they conceive of their publics: who they represent, whose interests they serve. The crucial difference is that the first type of culture war is a war on culture by those who exploit the financial and legislative power of the state to demonize art, attack artists, and defund institutions for political gain. The second type is a war to expand the terms of culture by those who are largely artists, and who want to participate fully in the art world even as they challenge its terms. We make a grave mistake, it seems to me, by conflating the two.

[…]

[The] title for this book—Whitewalling—[is] a neologism that expands in many directions: the literal site of contention, i.e., the white walls of the gallery; the idea of “blackballing” or excluding someone; the notion of “whitewashing,” or covering over that which we prefer to ignore or suppress; the idea of putting a wall around whiteness, of fencing it off, of defending it against incursions. The title acts as a signpost to the assumptions that guide the three narratives in the following pages. In each of these stories, the protests arose from a clash between three roughly-drawn factions: black people and their allies who recognized that the institutions involved were working to reinforce and center whiteness; those who insisted, often invoking the values of free speech, artistic freedom, civility in discourse, and anti-censorship, that the protests themselves were the “real” problem; and the institutions themselves, which found themselves forced to reckon in real time with who they are and who they are meant to serve.

Mine is not, at root, an aesthetic argument. It is a book about protest, and the way such protest grapples with art in order to lay bare the ways in which the art world is part of a much larger world.