This spring, the National Gallery of Canada launched “Gauguin: Portraits,” the world’s first exhibition dedicated to portraits by the famous 19th-century French painter. Ottawa is the only North American city to host the exhibition, which brings together roughly 70 paintings, sculptures, prints and drawings from Paris’s Musée d’Orsay, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among other international museums. There are high-tech elements too—like a 3D-printed version of a Gauguin sculpture visitors can touch, and an ultra-HD screen for zooming in on details from the paintings.

A lot has been promised for “Gauguin: Portraits,” including, as guest curator Cornelia Homburg put it, evidence that the artist “came up with a truly new vision about what portraiture could mean.” Homburg, who is based in France, worked on the show for four years. It follows her 2012 NGC exhibition, “Van Gogh: Up Close,” which was the gallery’s most visited show in two decades—a blockbuster, to be sure. The National Gallery, London, and its Canadian-born curator Christopher Riopelle helped develop “Gauguin: Portraits” and will host it in the UK this fall.

But there’s something missing from “Gauguin: Portraits” in today’s Canadian context, where many museums are actively working on Truth and Reconciliation report recommendations—including the NGC itself, which recently integrated its Indigenous and Canadian collections and is launching the next edition of its international Indigenous quinquennial in November.

What’s missing from “Gauguin: Portraits”—at least from my perspective as a white settler Canadian arts writer reporting on our museum sector—are programs and contexts that include perspectives from the Indigenous Pacific peoples Gauguin depicted, or that critically address the problematic issue of Gauguin’s relationships with Tahitian girls as young as 13 years old. All this is especially necessary given that Gauguin’s paintings, and his legacy in European art history, have had an outsized impact in defining the Pacific region and its people to outsiders.

“I feel, in the absence of perspectives from Tahiti, from Samoa, from Hawaii, that these are the main images people will see [of that region],” says Léuli Eshrāghi, a Montreal-based Australian curator, critic and writer of Samoan, Persian and other ancestries. “They’re a problematic painter’s vision and exoticization and simplification and abstraction of who we never were. I feel like that’s a really dangerous thing.”

The National Gallery of Canada’s new CEO Sasha Suda, who is white settler Canadian and formerly a curator of European art, agrees that more should have been done to consider Indigenous perspectives in the exhibition.

“For me, being new here, it’s a missed opportunity not to explore the broader discourse as it connects to our really important Indigenous and Canadian initiatives,” says Suda when asked about this problem. “It’s an important learning for us right now.” Following the opening, Suda and her team changed some of wall texts, and added new ones, to address the Eurocentric biases in the exhibition. But there is still much to be done.

The interior to the entrance of the “Gauguin: Portraits” exhibition features two Indigenous figures from Gauguin’s painting Barbarian Tales (1902). The European man also pictured in the painting is cropped out. Photo: Leah Sandals.

The interior to the entrance of the “Gauguin: Portraits” exhibition features two Indigenous figures from Gauguin’s painting Barbarian Tales (1902). The European man also pictured in the painting is cropped out. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Above the entrance to “Gauguin: Portraits” is a large banner featuring an Indigenous figure from Merahi metua no Tehamana (1893). Gauguin’s images of Indigenous women predominate in the National Gallery of Canada’s advertising of the exhibition. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Above the entrance to “Gauguin: Portraits” is a large banner featuring an Indigenous figure from Merahi metua no Tehamana (1893). Gauguin’s images of Indigenous women predominate in the National Gallery of Canada’s advertising of the exhibition. Photo: Leah Sandals.

A still from First Impressions: Paul Gauguin (2018) by Yuki Kihara. Five-part episodic talk-show series, HD video, 13 min. Commissioned by the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen and Milford Galleries Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand.

A still from First Impressions: Paul Gauguin (2018) by Yuki Kihara. Five-part episodic talk-show series, HD video, 13 min. Commissioned by the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. Courtesy of Yuki Kihara, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen and Milford Galleries Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand.

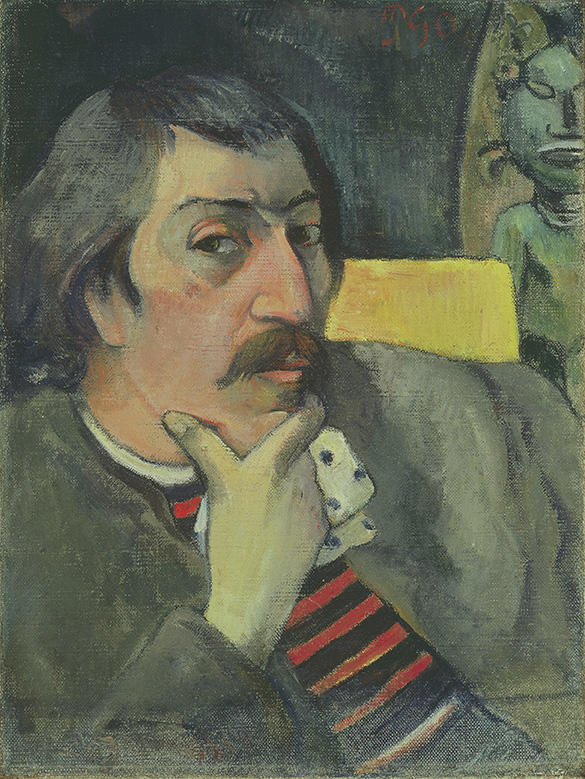

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Idol, c. 1893. Oil on canvas, 43.8 × 32.7 cm. McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas. Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay (1950.46).

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait with Idol, c. 1893. Oil on canvas, 43.8 × 32.7 cm. McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, Texas. Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay (1950.46).

Paul Gauguin, Woman of the Mango (Vahine no te vi), 1892. Oil on canvas, 73 × 45.1 cm. Baltimore Museum of Art. The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland (BMA 1950.213). Photo: Mitro Hood.

Paul Gauguin, Woman of the Mango (Vahine no te vi), 1892. Oil on canvas, 73 × 45.1 cm. Baltimore Museum of Art. The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland (BMA 1950.213). Photo: Mitro Hood.

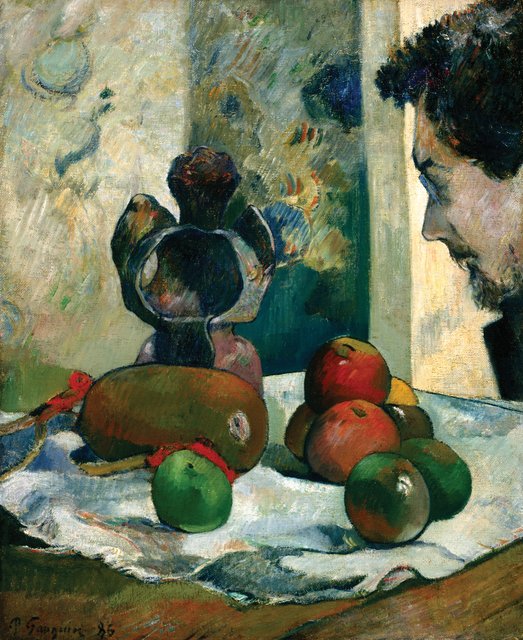

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Profile of Laval, 1886. Oil on canvas, 46 × 38 cm. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Gift of Mrs. Julian Bobbs in memory of William Ray Adams, 46.22, DiscoverNewfields.org (1998.167).

Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Profile of Laval, 1886. Oil on canvas, 46 × 38 cm. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. Gift of Mrs. Julian Bobbs in memory of William Ray Adams, 46.22, DiscoverNewfields.org (1998.167).

Paul Gauguin, Portrait of Meijer de Haan, 1889–90. Waxed distemper paint and metallic oil paint on oak, 58.4 × 29.8 × 22.8 cm. National Gallery of Canada. Purchased 1968 (15310) Photo: NGC.

Paul Gauguin, Portrait of Meijer de Haan, 1889–90. Waxed distemper paint and metallic oil paint on oak, 58.4 × 29.8 × 22.8 cm. National Gallery of Canada. Purchased 1968 (15310) Photo: NGC.