“Àbadakone” showed me that if there is one thing that Indigenous people are good at, it’s elevating materials some consider tacky, simple or poor quality into luxe and elegant forms of fine art. Think Dolly Parton’s Backwoods Barbie, but Indigenous (so maybe think Buffy Sainte-Marie?). Because, after all, isn’t being a little bit country what makes us Indigenous? We are the original rhinestone cowboys. There is inherent racism in the construction of a “lowbrow” aesthetic (which denegrates the aesthetics of camp) because Indigenous peoples, Black peoples and people of colour are the ones producing camp culture (see also: how racism and homophobia killed disco). Camp versions of weaving and fibre arts appear throughout “Àbadakone” as a reminder that Indigenous people were doing fibre works long before white artists caught onto its subversiveness. Navajo artist Melissa Cody blends traditional Navajo techniques with references to the pixelization of 1980s video games in her wool weaving World Traveler (2014). Haida artist Lisa Hageman Yajulanaas’s Raining Gold (2012–17) is a beautifully woven robe made from sheep wool and gold leaf that meditates upon the artist’s contemporary aesthetics and how their practice is simultaneously influenced by ancestral Haida design. Weavings by Cody and Hageman Yahgulanaas, blending ancestral techniques with new forms of story and knowledge production, are a reminder that Indigenous people were the original camp—a kind of pre-camp, if you will.

Weaving, for the artists of “Àbadakone,” is a powerful contemporary method for imaging futurist, utopian ethics. Mi’kmaq artist Ursula Johnson’s series Mi’kwite’tmn (Do You Remember?) (2014–)—wherein the artist hand-etched diagrams of baskets made by her great-grandmother into acrylic vitrines with birch-face plinths, thereby subverting the idea of a sterile, deadened museum artifact—asks audiences to not mistake the use of weaving as pure nostalgia. Hlubi artist Siwa Mgoboza’s The Ultrabeam (2017) is made from isiShweshwe fabric, glass beads, tulle and cotton thread, and imagines a utopian world called “Africadia.” The immersive rooms in “Àbadakone” also expose an Indigenous futurist ethics generated through the use of traditional knowledge—featuring exaggerated materials by Algonquin-French artist Caroline Monnet and a shadow-projecting glass light box by Dzawada’enuxw artist Marianne Nicolson—by acting as portals to Indigenous worlds.

The focus on universal textiles and weaving throughout “Àbadakone” is a conscious grounding of the feminine circles that sustain Indigenous communities. Eternity Kap Kanin (2012) by Sámi artist Inger Blix Kvammen, for instance, is a wearable neckpiece incorporating the intensive labour practice of Nenets women of the Russian Arctic with photographs documenting them. Anishinaabe artist Maria Hupfield’s installation Electric Prop and Hum Freestyle Variations (2017–18), comprised of plywood, a protest banner, lights, and objects made of felt, is a depiction of the politics of being an NDN grrrl activist today, and all the contemporary materials that Indigenous feminists transfer love of things onto. Hupfield’s protest signs wrap around the gallery walls and read “Land and, and, and…,” as a reference to urban Indigenous protests. Anger makes me a modern girl, as Sleater-Kinney would say. Found materials industriously used as protest objects also appear in Javanese artist Eko Nugroho’s What Else? (2008–18), the banner images embroidered over textile.

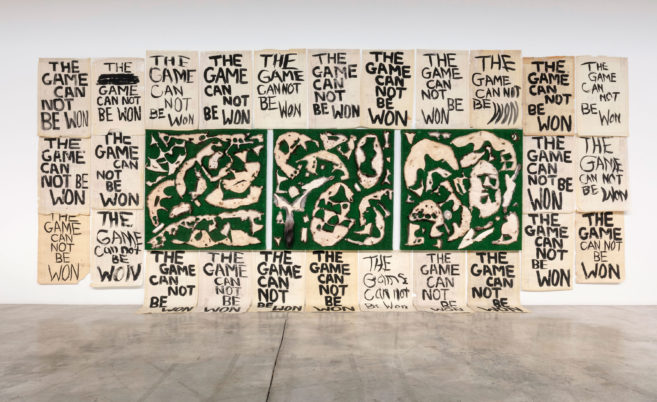

Mata Aho Collective, AKA, 2019. Installed at the National Gallery of Canada. Collection of the Collective. © Mata Aho Collective. Photo: NGC

Mata Aho Collective, AKA, 2019. Installed at the National Gallery of Canada. Collection of the Collective. © Mata Aho Collective. Photo: NGC