Many objects in the collections of major Canadian museums were acquired in the 19th and early 20th centuries—before the abolition of slavery, before the Civil Rights Movement, before the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—and were named by people from that time. As a result, many titles and descriptions still bear traces of terminology that is now considered racist, colonialist and offensive.

Over the last year, museums in Denmark and the Netherlands have committed to an update. In December 2015, the New York Times reported on the launch of a project at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam that will remove outdated, derogatory terminology from titles and descriptions in the museum’s holdings. Words being revised included “negro”; “Hottentot,” an insulting term meaning “stutterer” in Dutch, applied to South Africa’s Khoi people; and “Mohammedan,’’ an outdated word for a Muslim; as well as “Indian,” “dwarf” and others.

The Rijksmuseum met with some criticism for being “so politically correct,” according to the Times. But other museums followed suit. In June 2016, Hyperallergic reported that the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen, inspired by the Rijksmuseum’s project, took similar steps. The gallery updated 14 works that were previously titled “negro” and “Hottentot” with the word “African.”

Outside of galleries and museums, people in Canada are also seeking to rename features of their everyday landscape. In Ottawa in the 1990s, the Assembly of First Nations acted to relocate the Indian Scout statue, originally created in 1918 to kneel subserviently next to the statue of Samuel de Champlain, and in 2013 a group campaigned to give the scout a name of his own. In Quebec last year, more than 600 people signed a petition to “change the names of 11 geographic sites in the province that include the N-word or the word Nègre.” At Yale University in July of this year, at Calhoun College, named for an advocate of slavery, an offended employee took matters into his own hands, smashing a stained-glass panel depicting slaves carrying bales of cotton. “It’s 2016,” the employee told the New Haven Independent. “I shouldn’t have to come to work and see things like that.”

Reading these articles, I wondered how museums in Canada, a country whose colonial legacy is a direct continuation of the empire-building projects initiated by Denmark, the Netherlands and other European countries, treated the inevitable appearance of such terminology in their collections.

“We have a duty to be historically accurate—but we also have a duty to humanism”

A quick online search of the digitized items in the National Gallery of Canada’s collections reveals that the words “Eskimo” (685 entries), “Indian” (2080 entries), “primitive” (23 entries), “savage” (630 entries) and “negro” (116 entries) are all present in artwork titles.

Some of these numbers are misleading. “Savage,” for example, is a common surname so old that it was the first recorded in the Domesday book, but the word also appears in inarguably offensive usage—see Orpheus Instructing a Savage People in Theology and the Arts of Social Life (1791) by British engraver James Barry, or a lithograph by Honoré Daumier featuring his satirical “noble savage” character, Bineau, titled The Savage Bineau Having … at Last Found a Use for his Club (ca. 1850).

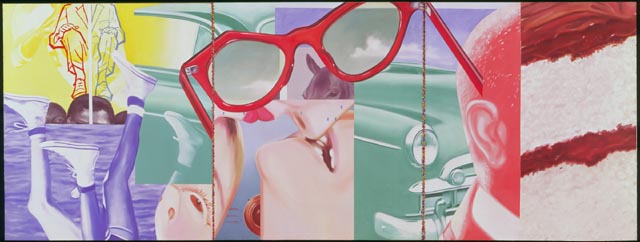

James Rosenquist’s Painting for the American Negro (1962), in the National Gallery’s collection, was made during the Civil Rights Movement in the US, and, though he’s been criticized for his decision, Rosenquist named his painting very deliberately. Replacing the offensive word in question would fundamentally alter the reading of the work. But it would be difficult to make the same argument for renaming Housing of a Primitive People in a Rainy Climate. Sudanese Negroes. A Sennar Hut (ca. 1852–61), also in the collection.

I spoke to Paul Lang, deputy director and chief curator at the National Gallery of Canada, over the phone, to inquire about the gallery’s policies and process in regards to this matter.

“Very few works have original documented titles,” Lang told me. “We inherit descriptive titles for artworks that were often written in the 19th century, and now of course we have greater sensitivity toward these subjects. The titles are often provided by collectors, curators, journalists, art critics and others. The only time we wouldn’t change a title is if it was the original title given by the artist, but that often isn’t the case.”

Indeed, many well-known artworks were not named by those who created them. Giorgio Vasari named Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting Mona Lisa, and Michelangelo’s David was named The Giant at the time it was made. Until a friend of his renamed it, Manet’s Olympia lived its first two years as Nude with a Black Cat (a rather unimaginative name that came from Charles Baudelaire). The somewhat lacklustre title James McNeill Whistler gave his famous 1871 portrait of his mother was Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1.

Lang feels it’s important to retain the original terms, even if they are offensive, because, “They are part of the history of the work. We have a duty to be historically accurate—but we also have a duty to humanism. We treat each work on a case-by-case basis, and always include the correction in the extended label.”

In the early 2000s, when Lang was chief curator at the Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève in Switzerland, a pastel came in by Rococo portraitist Maurice Quentin de La Tour. “It was very rare. The original title was included in the integrated label, which was part of the original frame, and it was Portrait de nègre. In the end, we decided to keep the original title, but added an explanation as to why in the extended label.”

When asked if there was any official policy in place for handling changes when new acquisitions come in at the National Gallery, Lang responded, “It’s just part of our DNA. It’s professionalism and our duty as humanists.”

National Gallery of Canada (no. 4735)

In the case of Negro Girl (1916) by A. Curtis Williamson, which is not currently on view, Lang told me that if they were to exhibit the work, they would change the title. “I doubt that is the original title,” says Lang, “and if it is not, we would change it. I think we would just call it Girl. After all, if the girl was white, we wouldn’t title the work White Girl.”

A full digitization of the National Gallery’s collection is in progress, and Lang estimates that more than half is currently digitized, although not all are available online. This process will make it easier to find and update titles that include outdated and offensive terminology.

The National Gallery is also currently undergoing an ambitious and significant change in how its collections are organized: by May 2017, the Canadian and Indigenous galleries, previously separate, will merge. The new galleries will present the interwoven and overlapping chronologies of art produced by Indigenous and settler communities, will put contemporary artwork next to historical art and artifacts, and works will be accompanied by signage in English, French and the language spoken by the creators of the objects.

“I have simply refused to use the word squaw on a label”

At the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, I spoke to communications and marketing officer Camille Dubois Crôteau, who told me over email that the curatorial team there likewise “works on a case-by-case basis,” but while they “don’t officially have a protocol or policy in place for this,” they have been, in recent months, “working on building something that can be applied to our approach moving forward.”

“In the meantime,” said Crôteau, “we are very aware of the need to treat these kinds of scenarios with sensitivity and integrity.”

While no official policy yet exists, Dianne O’Neill, associate curator of historical prints and drawings at the AGNS, remains firm in the approach she has taken for decades. “In the 20 years I have been preparing exhibitions of historical Canadian prints and drawings here,” she told me over email, “I have simply refused to use the word squaw on a label, even if it appears on the print, arbitrarily substituting woman.”

“When I used the print from Canadian Illustrated News for 14 December 1878 titled Negroes Bringing in Evergreens for the Arches,” she said, “on the label it appeared as Bringing in Evergreens for the Arches.”

Together, the AGNS’s curatorial team provided me with some examples of the sorts of situations that might arise as they catalogue artwork and plan exhibitions. They have been considering this matter in more detail as the collection is made readily available to the public with their new collection-management system. At present, they tell me that they manage it on a fairly consistent basis internally without a specific policy in place.

The first example they gave me was from their current exhibition, “Return to Nova Scotia.” The curatorial team encountered a historical print that included a visible racist term: a watercolour with the title Nova Scotia Squaw. Halifax, North America written on it in ink.

After consulting with Roger Lewis, curator of ethnology with the Nova Scotia Museum, who in turn worked with Dr. Bernie Francis, a member of the Mi’kmaq Membertou First Nation, the curatorial team elected to address the term in the extended label, explaining how it came about and how it evolved to become a disrespectful term. “We used the opportunity to identify the term and create more awareness about it both in the historical and contemporary contexts,” they explained to me over email.

The label reads:

Barnard

Act. 1815

Nova Scotia Squaw. Halifax, North America, 1815

Watercolour, ink and ink wash on paper

19.2 x 12.5 cm S.E.M.

Nova Scotia Museum Ethnology Collection. Acquired through the generous support of John Risley, John Bragg, the Nova Scotia Museum Board of Governors and the Canadian Maritime Heritage Foundation.

2015.13.7

A rare representation of a Mi’kmaw woman in traditional dress at the time of the War of 1812, possibly conducting commerce in a colonial store or the pantry of a colonial home in Halifax. The early nineteenth century was one of transition for Mi’kmaw culture and life, when traditional ways of life mixed with new colonial influences and industrialisation, but before the later establishment of a Reserve system. Note the crucifix worn around her neck, reflecting the conversion of many Mi’kmaw from traditional spirituality to Roman Catholicism, a process which had occurred throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The term squaw came about when the first European settlers heard the suffix skw at the end of Mi’kmaw words related to the female species, and often appears in historical documents and art. At that time skw was closer to skwa in enunciation. Eventually it became over-enunciated to squaw, a term which evolved over time from its original form to be disrespectful, but not necessarily abhorrent.*

*Linguistic interpretation courtesy of Dr. Bernie Francis.

The AGNS team says they are currently discussing a similar approach to be used in descriptions for other works in the collection.

When considering an artwork that contains offensive terminology made by an artist who is still alive, the AGNS team will consult them about modifying the title. They say the artists are usually amenable to this. If the artist is dead, they make a decision internally as to how they will modify the title, and will discuss with members of communities that might potentially be affected.

Like the NGC, the AGNS will keep track of the old title for reference purposes, but replaces all labels and publicly visible work with the new title. If there is an educational benefit in including an explanation as to why a word was modified, the curatorial team will include one, but certain changes are made without ceremony, such as updating to preferred spellings. O’Neill told me, “I don’t know I’ve been entirely consistent over the years, but usually I will substitute Mi’kmaq for Micmac (or the uglier, Mic Mac).”

“Portrait of a Haitian Woman does not tell the whole story—an enriched label is required to describe the reality of slavery.”

At the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, I spoke to Jacques Des Rochers, curator of Quebec and Canadian art (before 1945). He told me that there was no official policy in place for handling cases of offensive terminology in artwork titles, but provided me with some examples where the situation has come up, and the various ways it has been dealt with.

In a print by Inuit artist Niviaksiak titled Eskimo Summer Tent (1959), the decision was made to retain the word “Eskimo,” because editions of the print exist at other institutions, including the Winnipeg Art Gallery, and changing the title would cause complications when trying to trace the other editions of the work.

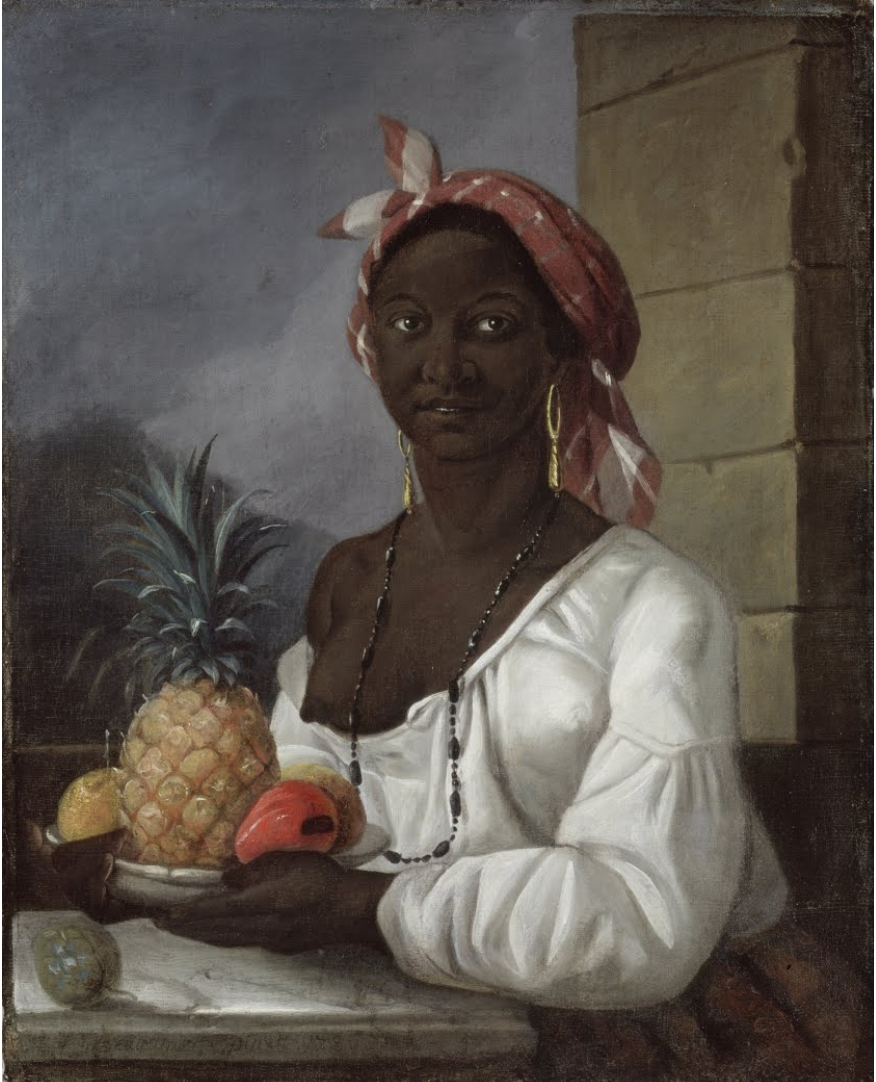

1786. Gift of Mr. David Ross McCord, M12067. © McCord Museum

An oil-on-canvas portrait currently on view at the MMFA, painted by François Malepart de Beaucourt in 1786, is the oldest-known portrait of a black slave in Canadian painting. Originally titled The Negress, the title was later changed to Portrait of a Black Slave by the McCord Museum, which owns the painting, and then Portrait of a Haitian Woman. Des Rochers felt it was absolutely necessary to include an enriched label next to the painting that acknowledged the reality of slavery at the time the painting was made. It explains that Beaucourt was a slaveowner and that the woman depicted was possibly 15-year-old Marie-Thérèse Zémire, a person listed as property in the will of Beaucourt’s widow.

1833. Gift of Keith Alison Handyside. Courtesy Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

A painting titled Mrs. Colin Robertson, née Theresa Chalifoux (1833) by James Bowman is on display in the same gallery. Des Rochers included a label with this work to explain the “history of the portrait and the origins of the sitter.”

The label reads:

James Bowman

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania 1793 – Rochester, New York, 1842

Mrs. Colin Robertson, née Theresa Chalifoux

1833

Oil on canvas

Gift of Keith Alison Handyside, inv. 1944.1255

Colin Robertson was an influential figure in the fur trade and became a chief factor for the Hudson’s Bay Company. In 1833, when he tried to introduce his Metis wife, Theresa Chalifoux, into the rudimentary society of the Red River Colony in Manitoba, the company’s bigoted governor, George Simpson, entered the following note in his famous Character Book: “Robertson brought his bit of Brown wt. Him to the Settlement this Spring in hopes that She would pick up a few English manners before visiting the civilized World…I told him distinctly that the thing was impossible which mortified him exceedingly.”

Back in Montreal, Robertson had James Bowman paint both his and his wife’s portrait in 1833. Mrs. Robertson is represented according to the precepts of white “polite society,” with all trace of her origin expunged.

“I’m not really comfortable with the idea of ‘world cultures,’ because in itself it’s a colonialist way of packaging.”

I also spoke to Laura Vigo, curator of Asian art. Vigo is the first curator of art from that region appointed in the history of the museum; before her, the museum employed consultants. Asian art is part of the so-called World Cultures department at the MMFA.

“I’m not really very comfortable with the idea of ‘world cultures,'” Vigo told me, “because in itself it’s kind of a colonialist way of packaging—you know, ‘the rest’ of the world—and it also make cultures sound like confined environments, rather than things with porous boundaries.”

“But before I came here,” she continued, “it wasn’t even called ‘World Cultures.’ It was ‘Ancient Cultures,’ which was even worse, because that’s a way of controlling a culture, by designating it as dead.”

There are plans to create a new space for the objects in the World Cultures collections on the fourth floor of the museum. Vigo’s curatorial vision is not to present the collection as a full and complete historical picture of these regions. On the contrary: “I want to show the fact that our collection is very minimal, but reflects ideas of China and Japan that were shaped and commodified for the Western market in the early 20th century. So as far as I am concerned our new display is about that: the ages of collecting. How the Canadian industrialists who built the collection, such as William Van Horne, were influenced by other trends, mostly in Europe. It provides a kind of time capsule, a historic reflection.”

“To me, what is important is to show the story of the collection,” Vigo told me. “How did these artifacts get here and what did they represent? We tend to forget that this was a very selective way of defining a culture—it’s the way colonialists, connoisseurs in the 19th and 20th centuries, thought about other cultures that were completely obscure to them.”

Even when an offensive term is not visible in the artwork or its given title, there are indelible traces of outdated, colonialist thinking present in the objects simply because of the history of their acquisition.

Increasingly, museums need to manage a careful balancing act between acknowledging difficult histories, yet avoid endorsing or replicating their damaging legacies. In this sense, the naming of objects is part of a wider reconsideration of the many different ways that histories can be told.

James Barry, Orpheus Instructing a Savage People in Theology and the Arts of Social Life, May 1 1791. Purchased 1975. National Gallery of Canada (no. 18351.1).

James Barry, Orpheus Instructing a Savage People in Theology and the Arts of Social Life, May 1 1791. Purchased 1975. National Gallery of Canada (no. 18351.1).