Of all the senses, smell is the most elusive. It’s invisible, often hovering just outside our awareness, and when it does seep through the crack of perception, we invariably let it drift back out of grasp as we lazily grope for the right descriptive words. Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer invented the word “ear lids” to draw attention to the immersive ubiquity of sounds in our lives. Well, perhaps there is also a place for nostril lids, since smelling—linked to breathing, to life—is even more pervasive. Ever present but usually only wobbling around the periphery of our attention, smells can send us, irrespective of our will, on great Proustian whooshes across space and time.

We become accustomed to the familiar, which explains why we seldom notice our own immediate smellscape. We notice smell when it is new, to log it, but more often smelling is remembering. The fabric-conditioner note found in the fragrance that artist Aleesa Cohene created as part of her immersive video installation Like, Like (2009) allows for a type of remembering that is simultaneously specifically personal and comfortingly generic. The bespoke scent, which also contains amber musk, bergamot, juniper bark and black pepper, among other ingredients, is diffused through the gallery space while a two-channel video shows clips of lovelorn women from Hollywood films.

To map smell is really to map our relationships with the world, and the people in it. To use smell in art, or to talk about how art smells, then, is not as niche as it might seem; it is a way of experiencing art that we have all at some point felt, if not acknowledged.

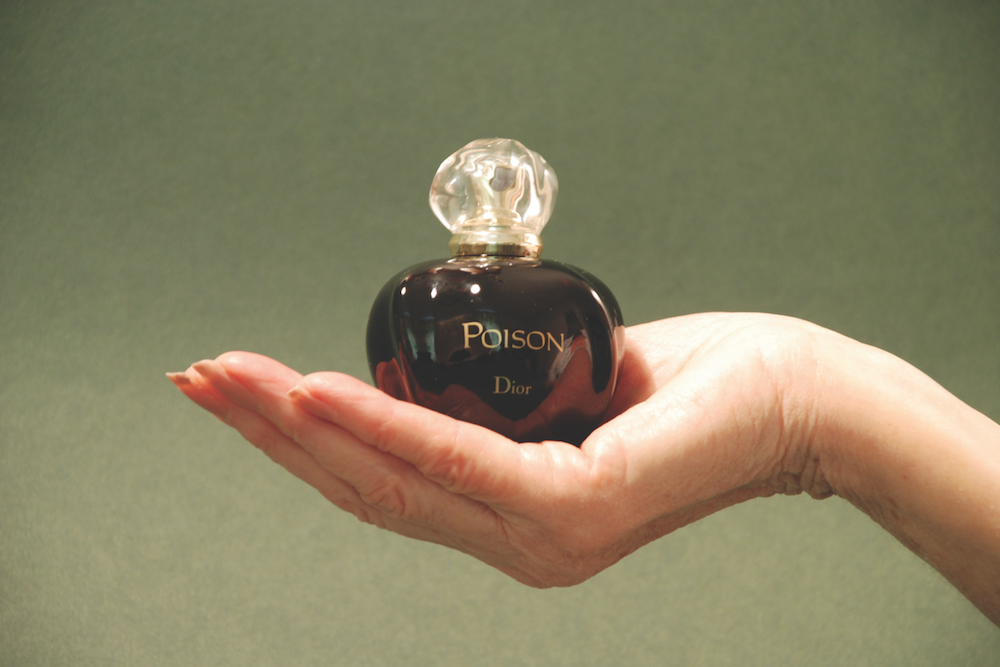

Art smells different to everyone because art is different to everyone. A publicist friend of mine described the smell of art as “beer, Botox and bullshit.” Two of these may not be smells, but the scene the description conjures is legitimately evocative. In 2013, Glasgow-based Canadian artist Clara Ursitti staged Poison Ladies, a gallery intervention, by sending 28 women wearing the Christian Dior perfume Poison to an exhibition opening. Most aged older than 60, the women comprised a demographic sometimes considered invisible, but because of the aroma they carried into the room, they became visible—impossible to ignore.

There is another perfume, Molecule 01, that since its release in 2006 has come to represent, for me, the smell of the art world. It disperses a cloud of familiarity with a form and force not dissimilar to Ursitti’s artwork. This expensive and addictive scent comes with its own stories, which are as powerful and appealing as its aroma: “It smells different on everybody” and “it’s made of pheromones” are untruths repeated by those wearing it, wafting their way around galleries on preview night.

But art is more than a social circuit, and the white cube does not smell of nothing. It smells of paint, carpet, air conditioning and dust, even before you put anything in it. And then there is the stuff art is made out of, the material elements—from paint, wood and metal to stranger things with stranger smells. The smell of art is most often a glorious mishmash of synthetic and natural worlds: turpentine, linseed and more sinisterly derived glues and gums, not to mention the myriad fluorescent pigments that come from minerals, roots and creatures, but glow with the association of less wholesome chemicals. Part of being an artist is being able to control the combination or transformation of materials, and to understand these things is, in part, to smell them.

I was once tasked by a composer to find a smell with no cultural point of reference—something that would bring with it no recollection of grandmothers, lost love or childhood trauma. The composer wanted a note, a colour—something that felt like the reverb or bass in music. It was to be felt, not smelled. The heavy, sonorous musk we selected worked wonderfully for the task at hand, but in another way we failed. Though all but a select few perfumers and flavourists would notice, the molecule, Iso E Super, is actually one of the most abundant aroma chemicals found in good-smelling things—it’s in both shampoo and cigarettes—and is the single component of that perfume so adored by much of the art world. It was only by using one of the most common, though exceptionally subtle, smells in our world that we could create the illusion of a smell with no connection to it.

Smelling is a very pure form of attention. As Susan Sontag reminded us in the year before she died, “It’s all about paying attention. It’s all about taking in as much of what’s out there as you can…. Attention is vitality. It connects you with others.”

Jo Barratt is a UK-based multisensory-design consultant and radio producer. He currently works for non-profit network Open Knowledge International, and co-hosts Life in Scents, a podcast about smell.

This article appears in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

Clara Ursitti Poison Ladies (performance documentation), 2013. Scent Intervention.

Clara Ursitti Poison Ladies (performance documentation), 2013. Scent Intervention.