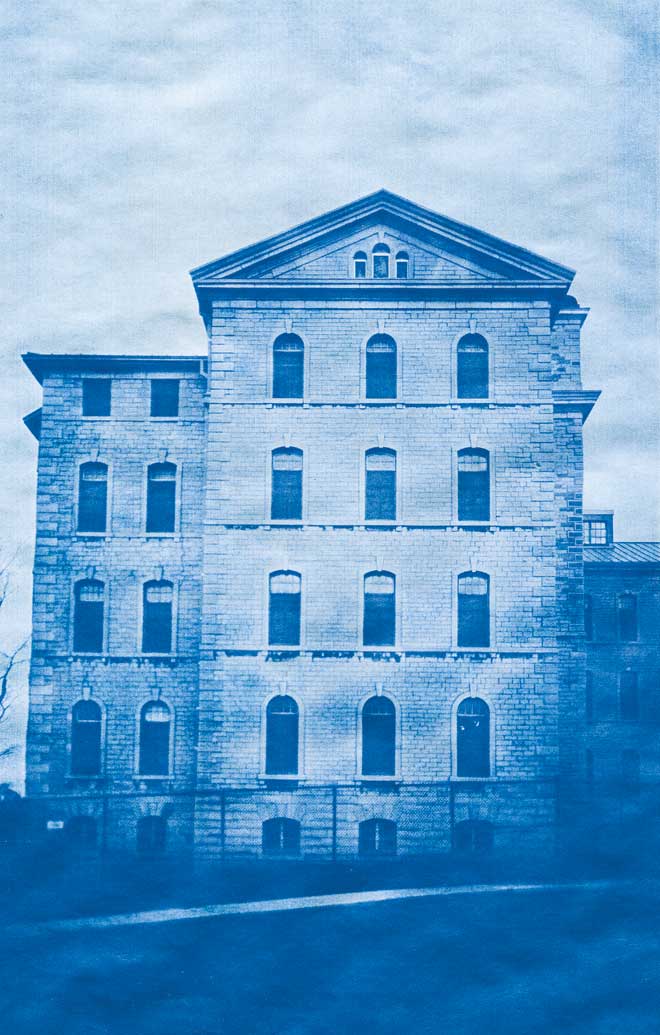

In 1859, construction of the Rockwood Asylum for the criminally insane began in Portsmouth, just west of the Kingston Penitentiary, in what is now known as Eastern Ontario. Built over nine years by penitentiary labourers, it was first established, in 1856, to house a class of criminal that disturbed the social order of both asylums and penitentiaries. The criminally insane included people who pleaded insanity at their trials, and convicts who had become insane while imprisoned.

Audible Songs from Rockwood, released April 21, is a collaboration between real musician Fiver and invented song collector Simone Carver. It compiles imagined songs from women held at Rockwood between 1856 and 1881. An excerpt from their conversation about the process is transcribed below.

Fiver: When you approached me to arrange these Audible Songs from Rockwood, I was compelled by the possibility of new narrative voices in traditional North American folk music. I love the genre, its melody and form, but often feel the songs sung from women’s perspectives occupy a narrow subject matter: woman as murder victim, woman as devil, woman wed to the devil.

While I deeply value the traditionalists’ approach to preserving song, I do not personally feel that these are emancipatory visions to repeat constantly. They impact the psyche. So, your proposal to broaden the scope of those voices was welcome. Songwriting is a refuge for those overactive and musically compelled minds dealing with trauma and crisis. They’re landlines for those of us communing with something indecipherable to our cohabitants. How did you go about collecting these songs from Rockwood?

Simone Carver: Most folk listeners are familiar with song collection by way of field recordings, like Alan Lomax’s recordings of Muddy Waters. Less popular was the methodology of ethnomusicologists like Paul Clayton. In 1950–51, Clayton travelled to Britain, collecting broadsides of traditional ballads. He then made recordings of himself playing them for release on Folkways Records, accompanied by deeply detailed liner notes describing the origins of the songs.

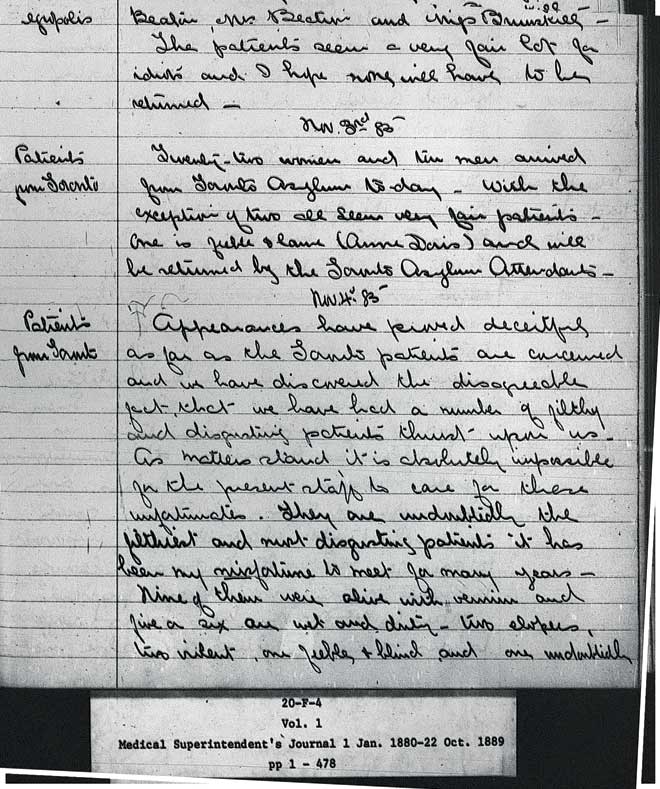

Our process of retroactive reconstruction is similar, with marked differences to deal with the inaccessibility of the inmates at Rockwood due to the temporal rift of 150 years. I’d access the case files of Rockwood’s inmates through the Archives of Ontario, throw on the white gloves, then flip through the brittle pages, reading the intake forms and ledgers, superintendents’ diaries, reports to the Dominion of Canada, inspectors’ memoranda, etc. From these I could find characters and, from them, I sometimes heard song.

F: Of the songs you handed me, there were definitely some I was incapable of singing. Does calling the album Audible Songs from Rockwood infer that some songs are inaudible?

SC: Yes. Some songs I simply couldn’t hear. Some case files read like a string of blanks—just two sentences for an entire human. I expected to find peculiar drama, but more often than not, these women committed crimes of poverty. Many were injured. They’d met obsolescence in the economy and wound up “vagrant” or committing larceny, and became unruly in whatever local jail.

“Haldimand County” belongs to a Scottish migrant who expected wealth on her arrival in the colony, and is instead used as cheap domestic labour, shuffled around the Haldimand tract as a squatter in the process of dispossession of land from the Six Nations. “Blue Fog” comes from the Irish immigrant who survived the famine, the ship and typhus, only to serve her oppressor, the British Loyalist. “Waltz for One” is the song of a 16-year-old whose father forces her to take an herbal abortive and sues her lover under the tort of seduction. Most of what I can know of these women is through records written by male cops, judges and doctors. These lead to maps and ledgers and newspaper articles also written by mostly British men.

F: It’s surprising how many of these songs were dreams, lies or metaphors that obscure fact. Songs of withholding. Then again, what kind of truth does a cop or a doctor usually know?

SC: Often the one that suits his purpose. I should admit I’m not a trained historian. If I was, maybe I wouldn’t have been so surprised at the ways the archive expressed itself as an apparatus of colonial power. Finding the words for these songs took a lot of secondary research.

F: So what you’re saying is that you invented these songs?

SC: No more than you invented me. No more than the psychiatrist invented insanity.

F: Go on.

“They are undoubtedly the filthiest and most disgusting patients it has been my misfortune to meet for many years—nine of them were alive with vermin and five or six are wet and dirty, two elopers, two violent, one feeble + blind, and one undoubtedly the champion ‘dirt-monger’ of Canada.” Journal entry by Rockwood medical superintendent William George Metcalf, November 4, 1883.

“They are undoubtedly the filthiest and most disgusting patients it has been my misfortune to meet for many years—nine of them were alive with vermin and five or six are wet and dirty, two elopers, two violent, one feeble + blind, and one undoubtedly the champion ‘dirt-monger’ of Canada.” Journal entry by Rockwood medical superintendent William George Metcalf, November 4, 1883.

SC: I got the distinct sense, looking at Rockwood’s history through its primary documents, that the asylum was invented for the purposes of the people running it. It was one of several places settler-colonial society could stow its casualties. John Palmer Litchfield, Rockwood’s first medical superintendent, wasn’t even a trained doctor. He’d been a medical journalist in London, England, versed well enough in medical jargon to convince the Australian colonists to fund an asylum there.

On discovering he was a fraud, they retracted his funding and threw him in a debtor’s prison, after which he eventually made his way to Montreal and befriended John A. Macdonald, who was none the wiser. And so he got the job running Rockwood. Picture that: his penmanship marking “Suffers delusions” on the women’s files. He thought it wise to seclude dozens of women in horse stables for the 11 years it took for the edifice proper to be planned and built—while male inmates were housed in a villa.

Under Litchfield, inmates were regularly blood-let and restrained, kept from human contact, treated with alcohol in the day and sedatives at night. He was also a teacher of medicine at the University of Queen’s College, and would have influenced patients all over the country.

F: Very shifty, to move around the world misrepresenting yourself with the intention to impose, and profit from, one’s design of the social order.

SC: Imperialist impulse, yes. To be clear, even though he was a fraud by his peers’ standards, those were also suspect. Throughout the mid-19th century, British doctors were claiming authority over medical practices in the colony. The midwives, who’d always attended births, and much of the homemade herbal medicine taught to settlers by Indigenous people, were delegitimized through licensing bodies that regulated medical education and pharmacies.

F: And Indigenous people? Where do they figure?

SC: In another one of the archive’s gaping blanks. The most I came across was in an article that mentions Rockwood in the Journal of Mental Science of 1869: “Among the so-called criminals in this asylum are two of the Aborigines, perhaps the only recognized instances of insanity occurring in the North American Indian…. The entire race appears free from hereditary taint.”

F: As I understand, there were already Methodist, Anglican and Roman Catholic initiatives for the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples—precursors to residential schools. I’ll admit that this was part of what made me question the importance of the material—it seems like on the state’s 150th birthday, to record the history of an asylum and once again centre the voices of settlers is not as important as imparting Indigenous history.

SC: I have two responses. First, that you’re right. But I don’t think songs from those histories are best relayed by a settler voice.

F: Yeah.

SC: Second, lodged deep in the thinking of many settlers is an epistemological racism learned partly from the way Canadian history is told. Canadian medical and legal systems are construed as fair and rational and legitimate, as institutions that brought about progress.

And yet, to hear from these women who were pathologized for showing the wounds of migration and patriarchy, only to be abused at the hands of a profiteering imposter, might shake the confidence people have in the root logic of settler society. Perhaps these stories can relieve us of the pride that muffles the question of decolonization.

Simone E. Schmidt is a songwriter born and raised in Toronto, who performs under the names Fiver and the Highest Order. Audible Songs from Rockwood is available on Idée Fixe Records.

This article appears in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. To get every issue of our magazine delivered to your mailbox before it hits newsstands, visit canadianart.ca/subscribe.

Jeff Bierk, Rockwood Cyanotype , 2015–16. Cyanotype, 30 x 20 cm.

Jeff Bierk, Rockwood Cyanotype , 2015–16. Cyanotype, 30 x 20 cm.

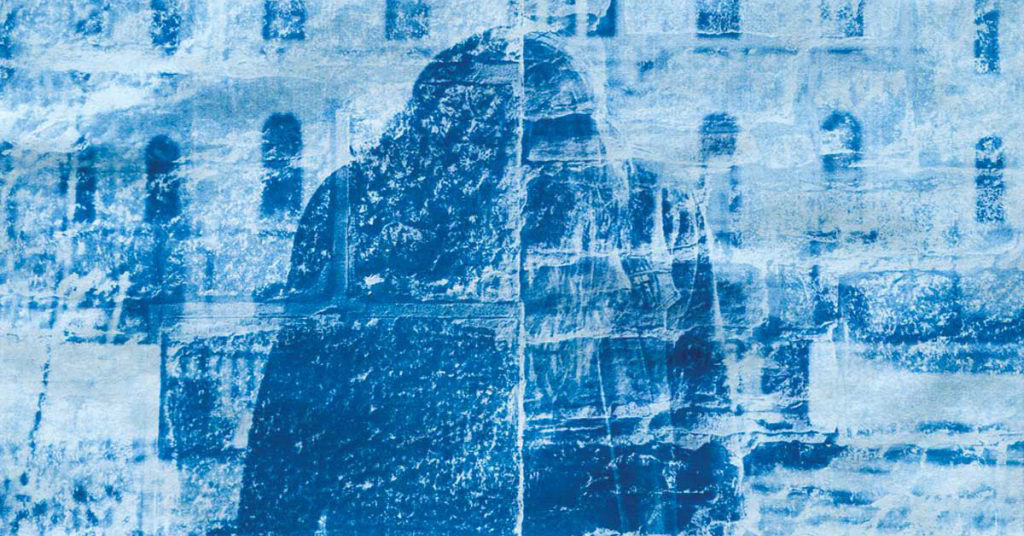

Jeff Bierk, Rockwood Cyanotype (Simone) (detail), 2015–16. Cyanotype.

Jeff Bierk, Rockwood Cyanotype (Simone) (detail), 2015–16. Cyanotype.