“Insurgence/Resurgence,” mâmawipaýiwin-winipêkohk ana.

Julie Nagam, mâmawinâtomew. Jaimie Isaac, mâmawinâtomew.

Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), wawêsîhcikêwinwikamik ana.

wâhkôhtowinwikamik ana. otâpasinahikewak nêki,

niwâhkomâkanak ôki. nîki-piskwatâw nîtisânak winipêkohk.

kikî-âkayâsîmonaw ayisk. kikî-wanisininaw. kinohtê-kîwânaw.

kinôhtê-mâci-nihta-kînêhiyawânaw. waniskâtân nîtisânitik.

“Insurgence/Resurgence,” this is a Winnipeg gathering. Julie

Nagam, she calls them together for the gathering. Jaimie Isaac,

she calls them together for the gathering. Winnipeg Art Gallery

(WAG), that is a building that holds decoration. That is a building

that holds relationships. Those artists over there, they are my

relatives. I spoke to my friends in Winnipeg. All of us spoke English

because we live in Canada. We were lost. We want to go home.

We want to begin becoming good at speaking Cree (here meant

as “our languages”). Rise up, my honoured friends.

I wish I could write this whole introduction in Plains Cree, one of my Indigenous languages. I can’t. My brain has been rewired by a foreign language that invaded my head, like an earworm in a Katy Perry song. I think in an English way now. I don’t know how to express the things I want to say or even if they are translatable because Cree ways of knowing are so radically different from English ways. Cree words express subject relationships—actions, verbs, doing— whereas English expresses object relations and relies on nouns, naming and claiming. My English-mindedness influences the ways I conceptually move through the world and how I describe my relationships, relations and actions.

“Insurgence/Resurgence” and its programming brought Indigenous people together from the farthest reaches of Turtle Island. Indigenous presence enlivened the WAG’s brick and mortar, colonial infrastructure and reminded me that Indigenous languages, and the art and curatorial projects they inspire, are activated through intimacy and togetherness. Language is shared over kitchen tables, taught by grandmas, aunties and cousins who passed on the relational teachings encoded in our descriptive language to one another over tea, beading and gossip. Because Indigenous languages are verb-based, the values and intentions they contain are action-based, meant to be activated within one’s relationships and in community, alongside kin. Indigenous languages are alive.

Indigenous language reclamation is integrated throughout “Insurgence/Resurgence.” Though I’m not certain reclamation is the right word. Reclamation feels like the child of an older generation intent on having their languages recognized and revitalized in the face of extinction. The artists in “Insurgence/Resurgence” express their languages as continually living, growing, evolving and surging in their minds and hearts.

For this sampling of Indigenous makers, doers and creators, language is an embodied practice, miyowawaynamowin (good creation), which allows Indigenous artists to communicate in ways that don’t always translate to English, or to written or spoken language, for that matter.

Giniw, onzaami-mindidod o’omaa akiing, gii-ozhaawashko-waabishkopizod zenibaang

okaading zhigwa oningwiiganaang.

Aabiding gii-agoozi waasiganeyaabiing, bengishid, egoojing ishpimakamig.

Ayagopizod wenizhishinid zenibaa’.

Giitwaam, giitwaam, giitwaam.

Gibichiimagak odaabaan gemaa bejiseg, ningoji ningaabiiwanong, bemiseg, nabakamigong.

Geyaabi gagwe-gidiskiid giniw. Gezika gichi-miikanaang, agaami-ashkaawi-waabizaawag

mishawaya’ii.

Mezhakwag ningiizhigom, aapiji gweyetamaan.

Mezhakwag ningiizhigom, aapiji gweyetamaan.

Mezhakwag ningiizhigom, aapiji gweyetamaan.

(eni-ishpishkaawaad), nawach gii-ani-gizhiiwe animikii. Mii-sa gezika daabishkoo

baakishkaag miinawaa gibishkaag, mii dash aanakwad ayizhi’aamagak. Mii dash I’imaa

gaa-ayaawaad gichi-bineshiwag, niizh bineshiiyensag gaye, daabishkoo odaminwaadeg

ishkode doodooskaabewaad weshkinawewaad wayaabamaawaad. Maagizhaa niizhing

dasing aanzinaamosiwang, mii minik gaa-waabamaawaad; mii miinawaa gii-gibo-aanakwag.

—Excerpts from Animikiikaa 10-97, Partial text excerpt from Mary Syrette from Ojibwa Texts Vol. 2 (1910), Contemporary translation by Roger Roulette (Winnipeg).

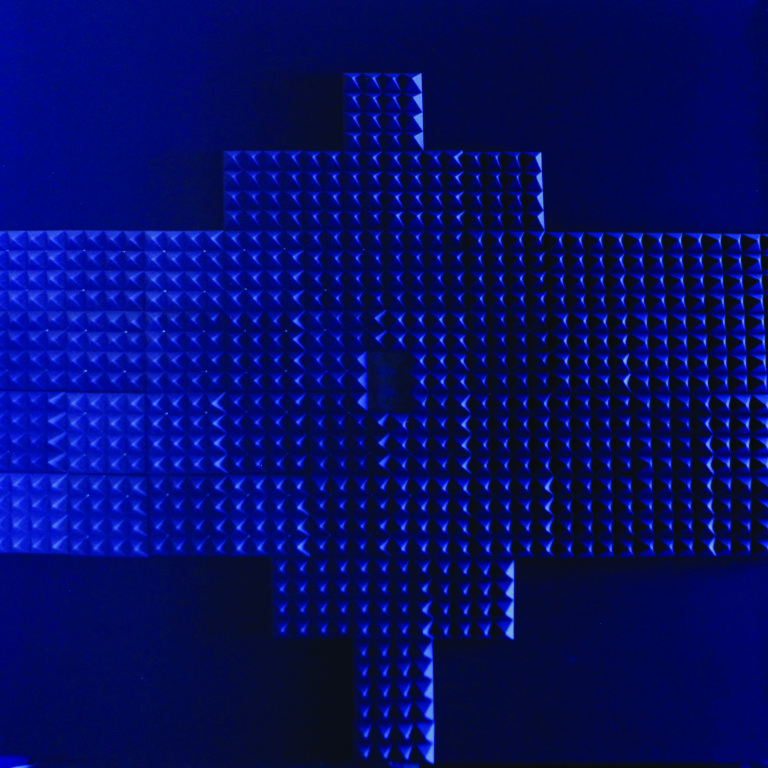

Scott Benesiinaabandan, Animikiikaa 10-97, 2017. 2.1-channel audio, acoustic

foam and installation materials, 3.04 m x 3.04 m x 60.9 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Scott Benesiinaabandan, Animikiikaa 10-97, 2017. 2.1-channel audio, acoustic

foam and installation materials, 3.04 m x 3.04 m x 60.9 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Scott Benesiinaabandan

Animikiikaa 10-97 (2017)

In What Now?: The Politics of Listening, Kade L. Twist of arts collective Postcommodity outlines what they call “transdisciplinary learning or listening.” Says Twist, “facilitating community epiphanies through collaborative processes driven by shared intentions…lead[s] to the production of co-defined metaphors that advance community self-determination.” An immersive soundscape that totally encompasses the listener in the dark (and because, as I know from being in a sweat lodge, we are all the same in the dark), Animikiikaa 10-97 can only be described as an epiphany. An open structure surrounds the visitor. In the darkness, voices speaking Anishinaabemowin are heard from all sides: we are forced to listen. Benesiinaabandan’s installation envelops us in Indigenous ways of knowing, in cosmologies that transcend those expressed in the English language— from dream worlds to a collective subconscious.

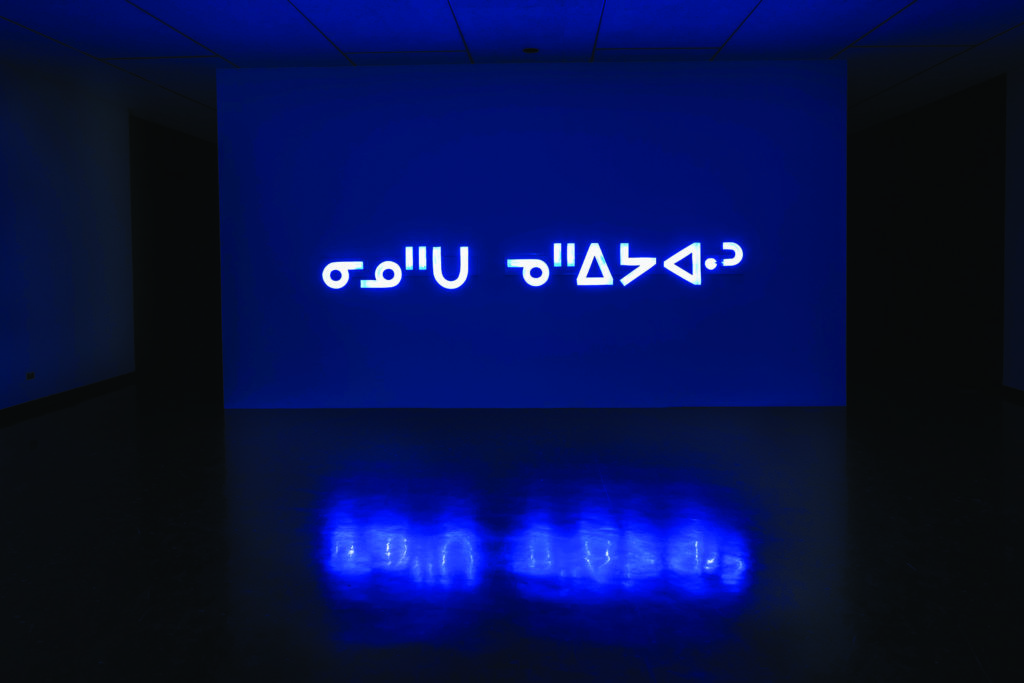

Joi T. Arcand, ᐁᑳᐏᔭ ᐋᑲᔮᓰᒧ e¯ka¯wiya a¯kaya¯s¯imo “Don’t speak English” (detail), 2017.

Vinyl, dimensions variable. Commissioned by Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo Scott Benesiinaabandan

Joi T. Arcand, ᐁᑳᐏᔭ ᐋᑲᔮᓰᒧ e¯ka¯wiya a¯kaya¯s¯imo “Don’t speak English” (detail), 2017.

Vinyl, dimensions variable. Commissioned by Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo Scott Benesiinaabandan

Joi T. Arcand

ᐁᑳᐃᐧᔭ ᐋᑲᔮᓰᒧ e¯ka¯wiya a¯kaya¯si¯mo “Don’t speak English” (2017)

Residential schools stole the words from the ancestors’ hearts, minds and tongues, and along with them, their spirits. During Arcand’s research, Darryl Chamakese, her frequent collaborator and translator, told her “syllabics” in Plains Cree is cahkipêhikana, translating to “marks representing the spirits of sound.” To me, Arcand’s work is land and spirit medicine (maskihki), taking up space and commanding presence in materiality, form and location. Arcand honours the Indigenous grandparents—who had their languages taken and cultural continuity severed from future bloodlines— by marking the space for Cree speakers and shifting the balance of power in colonial structures. Arcand marked the floor of the stairs leading up to the exhibition with Cree syllabics so they reclaim the ground, the land, for Cree peoples, and simultaneously refuse settler readings of the space. Cree speakers are now the ones chiding settlers for speaking out of turn, just as settlers used to punish our ancestors in residential schools: êkâwiya âkayâsîmo. Don’t speak English. Never forget you’re on Cree land, invader.

Jordan Bennett and Dee Barsy, Mawpile’n (Tie It Together) (details), 2017. Collaborative mural, acrylic on Dibond panel and vinyl reproduction, 2.4 m

diameter. Commission partnership between Wall–to–Wall Festival/ Synonym Art Consultation/Winnipeg Art Gallery Photo Joseph Visser.

Jordan Bennett and Dee Barsy, Mawpile’n (Tie It Together) (details), 2017. Collaborative mural, acrylic on Dibond panel and vinyl reproduction, 2.4 m

diameter. Commission partnership between Wall–to–Wall Festival/ Synonym Art Consultation/Winnipeg Art Gallery Photo Joseph Visser.

Jordan Bennett and Dee Barsy

Mawpile’n (Tie It Together) (2017)

There is a visual language to the quillwork of the Mi’kmaq, a stable ontology, the meanings of which are sleeping. The Mi’kmaq have been contending with colonial imposition for centuries—because their territories and homelands are on the East Coast—and the visual signifiers embedded into Mi’kmaq quillwork now lie dormant, waiting to be woken by Mi’kmaq peoples. Jordan Bennett visited Mi’kmaq quillwork in museums, in one instance alongside Roger Lewis, a Mi’kmaq curator, who cares for the quillwork at the Nova Scotia Museum. In doing so, Bennett sought to learn from the visualities of Mi’kmaq quillwork, utilizing what patterns are known and looking to relative nations that share a common language, to piece together what Mi’kmaq visual languages could have meant to his ancestors. But Mi’kmaq symbols, patterns, colouring and motifs are also revived to tell Bennett’s own stories, and the stories of the communities he works with, in the contemporary. Barsy’s paintings are intuitively informed and often feature bright, vivid colours, and geometric compositions and forms. Complex and layered, merging yet somehow still breaking apart, Barsy’s work is a visual articulation of her relationships. In the case of My Four Grandmothers, another of Barsy’s works featured in “Insurgence/Resurgence,” abstract figures containing a spectrum of saturated colours represent the diversity of Barsy’s four grandmothers. The figures are fixed on the canvas but denote movement— representing a visual language, beyond space and time, that seeps into relational ways of knowing physicality and Creation. In Mawpile’n (Tie It Together), Barsy and Bennett respond to each other’s work using visual languages grounded in their own unique aesthetics. While Bennett speaks from inside Mi’kmaq language, Barsy converses in aesthetics. Both transcend what some audiences might consider to constitute conventional communication and spoken language. Tie it together, they are saying—our languages, our lands and our love.

Joi T. Arcand, ᓂᓄᐦᑌ ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐘᐣ (ninohte¯- ne¯hiyawa¯n), 2017. LED and neon lights,

45.72 cm x 4.27 m x 25.4 cm. Collection Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Scott Benesiinaabandan.

Joi T. Arcand, ᓂᓄᐦᑌ ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐘᐣ (ninohte¯- ne¯hiyawa¯n), 2017. LED and neon lights,

45.72 cm x 4.27 m x 25.4 cm. Collection Winnipeg Art Gallery. Photo: Scott Benesiinaabandan.