Zinnia Naqvi

Public installation, Canada Line, April 2 to September 30

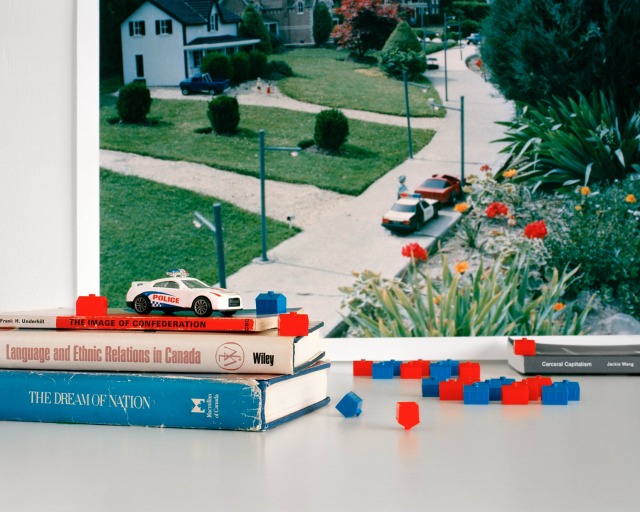

Each image from Zinnia Naqvi’s Yours to Discover series is a dense tapestry of meaning. Naqvi stages the immigrant dream—a washed-out, middle-class suburban bliss—and unravels it at once, illuminating the threads between nostalgia and colonization. A self-aware critic, Naqvi has a humour that gets punchier the more it is taken seriously: manicured nails and lawns, stacks of heavy-hitting titles on race, toy cop cars and Monopoly houses. Installed at the Broadway–City Hall Skytrain station, a literal cog in the facilitation of movement and economy, Yours to Discover is cheeky yet incisive, inviting us to think critically about our attachment to place. —Coco Zhou, editorial resident

Will Kwan, Endemic #3 (Having a field day), 2021. Détourned press photo (David Rodriguez/The Salinas Californian), laminated inkjet print.

Will Kwan, Endemic #3 (Having a field day), 2021. Détourned press photo (David Rodriguez/The Salinas Californian), laminated inkjet print.

Will Kwan

Centre A, continues to May 29

“There are more important things than living.” So said Texas lieutenant governor Dan Patrick in April 2020, opining for an end to pandemic lockdown. Will Kwan détournes this phrase in Death Cult #1 (There are more important things than living) (2021), a black granite slab etched with Patrick’s visage and quote. In “Exclusion Acts” Kwan showcases this and other sharp reflections on pandemic, capitalism and white supremacy. Kwan is a thinker and maker who has been critiquing colonialism, racism and commercialism for 20 years; to witness him going to work again, subverting these phenomena in link to a grievous and heightened moment, feels vital. —Leah Sandals, content editor

Jordan Bennett, al’taqiaq: it spirals, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

Jordan Bennett, al’taqiaq: it spirals, 2020. Courtesy the artist.

Jordan Bennett

Public installation, Dal Grauer Substation, April 2 to March 1, 2022

Artist’s talk, April 25, via Zoom

Mi’kmaq artist Jordan Bennett is giving a free artist talk on his photo mural al’taqiaq: it spirals, which features a moose skull gifted to the artist by a family friend. Bennett painted the skull in bright patterns reminiscent of the patterns found on traditional Mi’kmaq quillwork. In his talk, Bennett will discuss his practice and explore the visual cultures of the Mi’kmaq and Beothuk peoples of his home, Ktaqamkuk. —Ossie Michelin, editor-at-large

Vivek Shraya, Coming Out Clown, 2019. Inkjet print, 106.5 x 122 cm. Courtesy of the Artist

Vivek Shraya, Coming Out Clown, 2019. Inkjet print, 106.5 x 122 cm. Courtesy of the Artist

Vivek Shraya

SUM Gallery, April 1 to July 1

Artist’s talk, April 3, via Zoom

Multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shraya merges tragedy and humour seamlessly into her playful yet compelling photo exhibition “Trauma Clown.” The artist poses as said “trauma clown,” accentuating the contentious desire by audiences to consume her pain as her success grows. Shraya performs her trauma in order to keep up with the insatiable demand for her anguish, which presents a dynamic and powerful message in her solo exhibition. —Adrienne Huard, editor-at-large

Erika DeFreitas, at the very point where words fail us; (the old word foi, “faith”), 2016. Digital inkjet print, 67.73 x 43.04 cm.

Erika DeFreitas, at the very point where words fail us; (the old word foi, “faith”), 2016. Digital inkjet print, 67.73 x 43.04 cm.

Erika DeFreitas

Art Gallery at Evergreen, February 13 to April 25

The clarity of Erika DeFreitas’s gestures and objects in the photo frame, ever in acts of searching, is a slow-burn kind of magic. These sharp edges of fragments—whether of performance, writing, still-lifes or research processes—can appear like collages or mise-en-scènes of unanswered questions. Sometimes the search is for who and what is lost from canonical art histories, or about relations marked by hands and bodies. In “close magic” many of the works drawn from the past five years also feature DeFreitas’s mother and show the two together, giving spatial form to quietly monumental intimacies. —Joy Xiang, assistant editor

Zinnia Naqvi, The Border Guards Were Friendly, 2019. Courtesy the artist.

Zinnia Naqvi, The Border Guards Were Friendly, 2019. Courtesy the artist.