In his 1990 book Le Contrat Naturel, philosopher Michel Serres called for a new type of politics in the face of catastrophic environmental change that has only escalated in our own time. Serres referred not only to a reimagining of the polis, the human-built city-state, but also the rejoining of the social and natural worlds in contract: an acknowledgment of the forces that have always bound humans to their environments.

Now, a new public artwork by Duane Linklater in Toronto’s Don River Valley aims to operate on this scale, inviting us to de-naturalize and re-naturalize what cities are made of, and how they came into being.

Linklater’s work for the Don Valley, due to be unveiled in September, comprises cast concrete sculptures—reconstructed copies of the gargoyles and grotesques that watch Toronto’s denizens from atop the city’s historic architecture. The artist’s replicas will be tucked into what is formally known as the Don River Valley Park, a hinge space connecting Toronto’s downtown core to its east end. The first of several planned works curated by Kari Cwynar, these will be part of an art trail and revitalization program organized by non-profit organization Evergreen in partnership with the City of Toronto.

Introducing quotations of historic architecture into the valley promises to reorient us to the material origins of Toronto—its “substrate,” as the artist calls it. The valley’s rich clay deposits were once the source of bricks that laid the city’s foundations. After the project’s launch, trail-goers will come upon Linklater’s fragments as eight standalone sculptures. In a clearing just north of the Bloor Viaduct, they are intended to provoke an uncanny recognition of their sources.

Ordinarily policing the borders between a building’s interior and exterior spaces, the gargoyles will become the sentinels of another threshold: the urban ecological park. But the park improvements are only the most recent events in the Don Valley’s storied past.

Recorded as both Nechenquakekonk and Wonscotonach in Algonquin language, the river was part of an ancient Indigenous trail network connecting Lake Ontario to the upper great lakes, and it was prized by the Wendat, Haudenosaunee and Anishnaabek Confederacies as a seasonal, resource-rich terrain.

These resources made the river and its surrounds an ideal asset for Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe’s nearby colonial settlement of York, where he could also project his memories of the River Don in South Yorkshire, England. Starting in the 1700s, the valley became a ground for farms, mills and factories.

By the late 1800s, the river’s flow could not keep pace with unchecked industry, and the polluted Don was straightened. The river bent to the desires of industrialists, a fitting metaphor for the ways that Indigenous landscapes are reshaped by colonial imperatives.

Photographer unknown, Don Valley Brick Works, circa 1891. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 1128, series 379, Item 1160.

Photographer unknown, Don Valley Brick Works, circa 1891. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 1128, series 379, Item 1160.

Linklater, who is Omaskêko Cree from Moose Cree First Nation, sees his practice as connected to these longstanding and embedded histories of the site.

“Colonization is not this historical thing that happened in the past,” he explains. “It’s an ongoing, evolving project that’s happening right now. Even though the extraction of this clay happened 200 years ago, they’ve moved on to something else. It’s oil, or it’s gas. It’s still resource extraction and it still requires the violent removal of Indigenous people off the land to complete that extraction.”

Although Linklater’s body of work varies across materials and sources, much of it questions the Enlightenment categories that continue to govern settler-colonial logic. In his 2012 thesis work, the artist planted 12 blueberry bushes outside the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College, part of an investigation into Cree language structures that divide nouns along animate and inanimate lines (as opposed to romance languages that divide things between masculine and feminine). As they grew, the blueberry plants became animate agents outside the gallery walls, testing the natural and the artificial limits of the exhibition system.

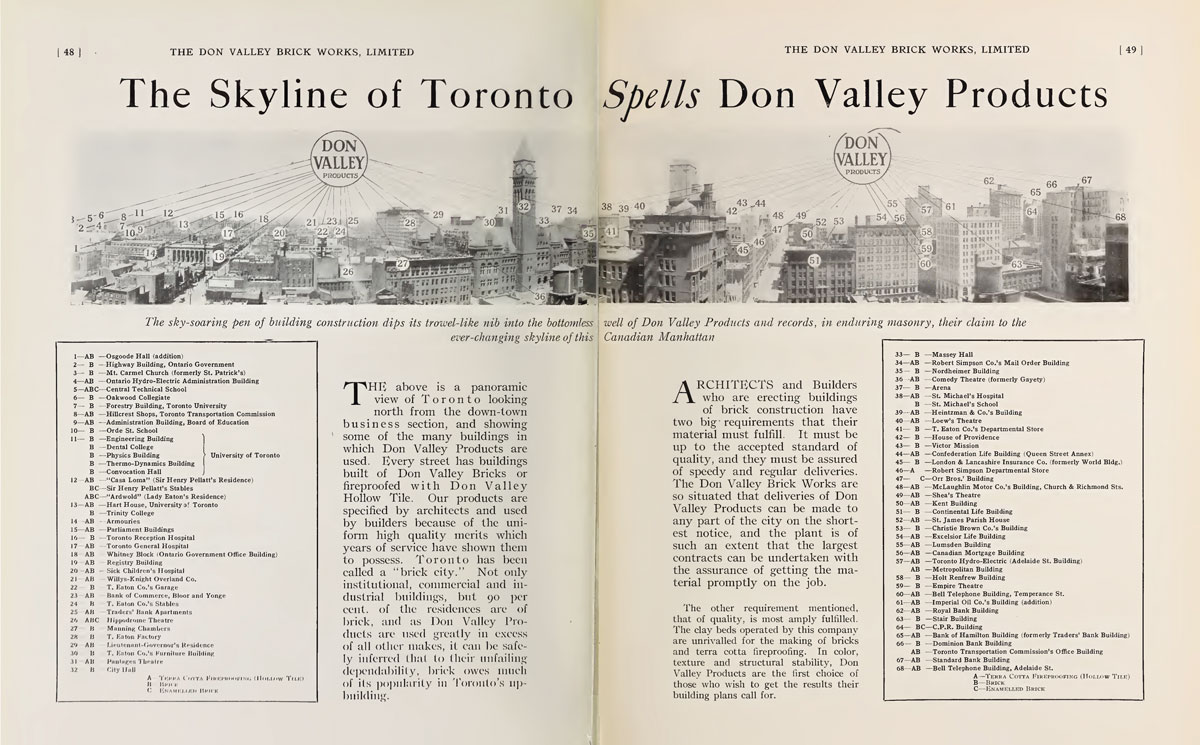

Spread from Beauty, Permanence and Individuality, published by the Don Valley Brick Works Limited in the early 1920s.

Spread from Beauty, Permanence and Individuality, published by the Don Valley Brick Works Limited in the early 1920s.

Whereas a monumental sculpture like his Mikikwan (to be unveiled in 2018 at Edmonton’s Indigenous Art Park) replicates a 9,000-year-old bone hide scraper in concrete, Linklater’s Evergreen commission turns its archaeology toward colonialism’s objects. Don Valley clay makes up the artifacts Torontonians move within, such as brick-clad restaurant interiors, red pressed-brick apartment blocks, edifices of higher learning and grand concert halls. Linklater wants the trail-goer to seek out the source of these copies around Toronto’s skyline. Roughly to-scale, the beasts will be brought up close to a new, ground-level visibility.

The stone-carved and terracotta grotesques on buildings like Old City Hall—designed by Edward James Lennox in 1887—functioned on multiple levels: to funnel rainwater away from the structure and as a means of retaining links to medieval, and even pagan, religious vocabularies within the realm of the secular. These features are not just remnants of Toronto’s oldest infrastructure, but also examples of a popular High Victorian Gothic and Romanesque Revival.

Photographer unknown, Old City Hall—gargoyle on tower, 1921. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 1, Item 478.

Photographer unknown, Old City Hall—gargoyle on tower, 1921. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 1, Item 478.

“At that particular time, the British empire was really disseminating itself through architecture,” remarks Linklater. On the one hand, it could be replicated in cities as diverse as London, Mumbai, Singapore and Sydney, but on the other, its specificity questions the willful blindness of Toronto’s place within this imperial network. In the present-day metropolitan financial centre, these gargoyles are testaments to the enduring legacy of the city’s fabric, the invisible labour of its craftsmen, and architecture’s self-perpetuating ideologies.

As a present-day urban borderland, the Don River Valley is caught between a highway and a rail corridor, with pockets of woodland persevering like islands in a sea of pavement. At its industrial channeling, vines, wildflowers and weedy undergrowth push up through the space between asphalt and rail spike. Deer, rabbits, cranes and coyotes share space with spandex-clad cyclists.

Soon joining these residents of Toronto will be creatures leaning and lying in state: antecedent ruins, part of Toronto’s ecological life cycle. It remains to be seen what role the Don Valley art trail, aspiring neither to a Manhattan High Line model nor a sculpture-park model, will play in the city’s cultural life. Linklater’s work signals that it won’t be a retreat from the city, as so many urban ecology projects promise, but will unearth Toronto’s hybrid—if not monstrous—nature.

This post is adapted from the article “Monsters of the Urban Unconscious,” first published in the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. This post was updated on June 8, 2017, as new information became available about delays the City of Toronto is experiencing in its work on the Don Valley; as a result, the installation is now due to launch in September, not July.

Photographer unknown, Old City Hall gargoyle, Terauley Street, 1920. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 1, Item 350.

Photographer unknown, Old City Hall gargoyle, Terauley Street, 1920. Courtesy City of Toronto Archives. Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 1, Item 350.