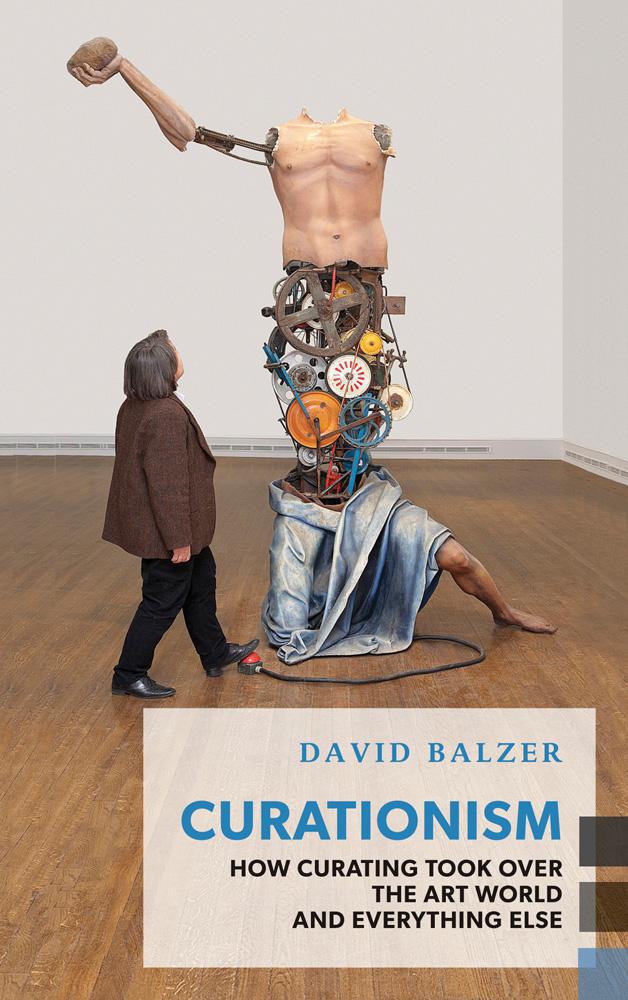

How did curating, once a term associated solely with the art world, attach itself to so many other spheres of life? This is a question Canadian Art associate editor David Balzer investigates in his new book Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, which Coach House Books will release across Canada on September 9. Find out more in this excerpt.

Miami’s South Beach is nothing like a white cube. On its easternmost side, along Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive, lies an impressive fleet of art deco hotels and, among them, the mansions of the resort neighbourhood’s current and erstwhile residents, from J. C. Penney to Gianni Versace, who was shot dead on his front steps in 1997. Everywhere is colour, traffic; life is instinctive, vulgar, dangerous, fun. The cacophony of capitalism defines the area, from these hotels, to the clustered, modest houses and apartment buildings lying slightly west of them (many, in their lingering decay, redolent of South Beach’s 1970s and 1980s depression—a period, with its cocaine dealers and crime, depicted in Brian de Palma’s 1983 film Scarface), to busy Lincoln Road, one of the U.S.’s first pedestrian malls, and its surrounding, riotously colourful surf stores.

December is tastefully warm in South Beach. The sun toasts rather than scorches. Historically, this has not been a big tourist time, but over the past decade or so that’s changed. I arrive in 2013 as a journalist, part of the hordes of mostly Europeans and Americans who have come to see Art Basel Miami Beach.

Art Basel typifies the ever-growing popularity of the fair in contemporary art, in which international commercial dealers converge in large cities at convention centres, piers, custom-built tents and hotels, securing high-priced booths in which to display and sell work from their stables of artists. Founded in Basel, Switzerland, Art Basel chose Miami Beach as an outpost more than a decade ago because of the wealthy Miami collectors who frequented its flagship event. Since then, around two dozen fairs have cropped up alongside Art Basel Miami Beach, most within walking distance—to say nothing of the myriad of parties, pop-up shops and ribbon cuttings that have come to comprise what is now Miami Art Week. South Beach is not transformed so much as intensified: more preening, more plastic surgery, more partying, more celebrities. Contemporary art seems put there by a production designer. Depending on how you see it, it’s either the best or worst kind of ambient noise.

Much has been written about Art-Basel-as-Wasteland. In a 2012 Slate piece entitled “The Eight Worst Things About the Art World,” fashion writer and Barneys New York “creative ambassador” Simon Doonan put Art Basel at the top of his list, snidely describing it as “overblown…[with] all that craven socializing and trendy posing.” There is a lot of art at Art Basel, to be sure, but what, implies Doonan, does it add up to? As if at a crowded, expensive party, works jockey noisily for attention, devoid of gravitas and thematic order. It is no museum or gallery, in other words. Curators, those trusted sybils of the contemporary art world, are conspicuously absent.

Or are they? Famously, advertisements for bars and events are towed by planes above South Beach’s long, populous white-sand beach. I go swimming one day, looking up from the crashing waves to see a different banner: “HANS ULRICH OBRIST HEAR US.” I laugh. It’s such an obscure plea—a knowing combination of unctuousness and plaintiveness. Hans Ulrich Obrist is one of the world’s top curators, and a few nights previous I had attended a panel discussion he had moderated between Kanye West and architect Jacques Herzog. (Obrist calls both, to varying degrees, friends.) Clearly, Obrist is here. But why?

The banner’s culprit was Canadian artist Bill Burns. Over recent years, Burns has made drawings, postcards, sculptures, watercolours and digital mock-ups addressing a variety of artworld authorities. The works express (and parody) the desperation and vulnerability felt by contemporary artists when fathoming the internationally known directors, curators and collectors who could make or break them. One Burns work is a proposal to affix a large sign to the roof of London’s Tate Modern reading “Hans Ulrich Obrist Priez Pour Nous” (in English, “Hans Ulrich Obrist Pray For Us”). In Miami, Burns hired airplane banners every day to make similar appeals, not just to Obrist, but to other power or star curators, like Hou Hanru and Beatrix Ruf.

It’s likely the beach crowd stared up in indifference at Burns’ banners. Outside of Obrist, is Burns certain anyone he had appealed to by name was actually present at Art Basel? “I have no clue,” he tells me. “The fairs are very big events, but they take a certain kind of personality to enjoy, like going shopping at Christmas.” What would a curator do at Art Basel Miami Beach? “It’s true that curators over the last two hundred years have been understood as taking on a kind of public service role. But now there’s a curious mixed economy in the art world. A curator’s job is often, at a fair, to cajole a collector into buying something for a museum—which I’m sure, for many, is not very pleasant. Artists, curators, collectors: we’re all part of a regime. I’m part of it as well. You are too.”

After seeing Burns’ banner, it occurred to me I was in eyeshot of the fuchsia tent of Untitled, one of Miami Art Week’s newest fairs, whose press materials emphasized its use of a curator, Brooklyn’s Omar Lopez-Chahoud. Lopez-Chahoud selected the galleries for Untitled, in some cases overseeing the arrangement of the fair’s booths and works. But Untitled’s gambit is not, in fact, novel. There’s Frieze London, and now Frieze New York, both of which rigorously jury their exhibitors, using curators to handle “special projects” such as sculpture parks on their tent grounds. And Frieze’s template is arguably Art Basel’s, whose former director, Samuel Keller, pushed curation to the forefront of the fair’s brand (in Switzerland and in Miami), collaborating with Obrist as early as 2000 to launch, at first, a series of talks at the Swiss fair.

Now, within the sterile, chaotic confines of the Miami Beach Convention Center, there are, for instance, curated sections for artist films and videos. Art Basel Miami Beach’s Nova and Positions sectors, the former meant for gallerists to display new works and the latter for gallerists to showcase the work of a single artist, do not have apparent curators, but suggest a “curatorial sensibility”: things judiciously selected and sleekly arranged, granting the fairgoer an experience much closer to that of a gallery or museum. When one considers Burns’ (correct) guess that curators also come to fairs to acquire art for their respective institutions (or, more frequently, to function as advisors for trustees and the like who hold those institutions’ purse strings), the fair becomes not anathema to curators, but specifically tailored to them. They occupy—and when not occupying, compellingly inform—both of the fair’s essential roles, those of buyer and arranger-facilitator.

If curation is everywhere, it is also both strangely embodied and disembodied. The curator is no longer just an art-world figure. Within the art world, a select number of curators like Hans Ulrich Obrist dominate their institutions but also transcend them, playing roles in media and culture. Outside the art world, curation is powerful but also diffuse. Celebrities act as curators not just for exhibitions, but for music festivals and boutiques. We “curate” in relation to ourselves, using the term to refer to any number of things we do and consume on a daily basis. Curators are visible in so many likely and unlikely ways. Are we witnessing their ultimate triumph, or a troubling, fascinating moment of their undoing?

Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, by Canadian Art associate editor David Balzer, will be released nationwide September 9, with related events in Montreal and Toronto through September and October—including an October 25 panel at Art Toronto as part of Canadian Art‘s 30th-anniversary Generation(s) series. For full details and to preorder the book, visit the Coach House website.