The most famous Medusa in art is by Caravaggio, a commission for the Cardinal del Monte painted on a ceremonial shield—and so an echo, in the manner of a stage prop, of the original Medusa’s-head “shield” Perseus carries in Greek myth to ward off his adversaries. Of course, Caravaggio’s painting doesn’t turn its viewers to stone, but it does force them to contemplate the violent implications of looking, while also acting as a brazen statement of purpose by the young artist. Its resemblance to the contemporaneous figure in Caravaggio’s Boy Bitten by a Lizard also suggests ambiguous gendering: according to art historian John L. Varriano, “the face may be a transgendered self-portrait.”

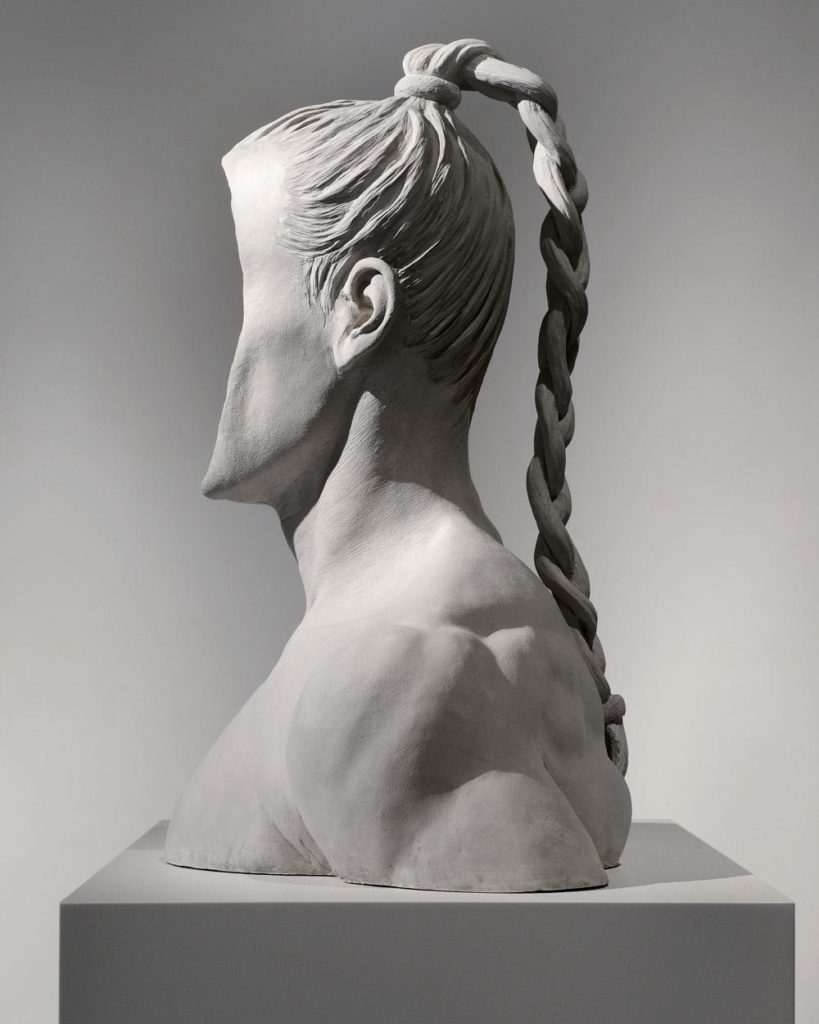

Chris Curreri’s current exhibition at Toronto’s Daniel Faria Gallery is called “Medusa” and cleverly rummages through such ambiguities. In the centre of the gallery is a cement bust with its face cut off. The model represented—a male bodybuilder—was featured in photos in Curreri’s previous exhibition with the gallery, but by virtue of the bust’s absent face, as well as its ponytail and rounded, overdeveloped pectoral muscles (which resemble breasts), it is, like Caravaggio’s Medusa, ambiguously gendered. If Mapplethorpe was evoked at Curreri’s last show, he is here as well, with the bust suggesting bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, whom Mapplethrope photographed, in addition to those male bodies of Mapplethorpe’s better-known work.

I was additionally reminded of Camille Paglia’s description of the Venus of Willendorf in Sexual Personae: “Her facelessness is the impersonality of primitive sex and religion….She stifles the eye. She is the cloud of archaic night.” Curreri’s bust is part Venus of Willendorf. Similarly absent of face, it is all body, but an edited, chiselled, aestheticized one, confusing civilization/nature and conscious/subconscious binaries. The sculpture’s lack of features prompts us to look for faces (or, rather, animus—that is, spirit) in non-facial forms.

The curving, bundled abstraction of musculature is also evoked by a corresponding suite of black-and-white photos of clay remnants of student projects from a class Curreri had taken at Toronto’s Gardiner Museum. What might be considered dead or ugly in these remains becomes living and beautiful in the photos. In some, Curreri adds a solarized effect, in which blacks and whites are reversed, and shadows or voids become bulbous, or vice versa. The clay remnants resemble the snakes of Medusa’s hair, and thus appear phallic, but seen piled together and awaiting reshaping into raw material for future use, they are mostly a glorious mess of openings and closings—of, perhaps, genitalia and erogenous zones. And in a nice touch, the photos are printed relatively small, matted by a large white space that invites the viewer to come and peer, and make the unassuming momentous.