As we shelter in place, scan for losses in our communities and dodge oncoming pedestrians we meet in the streets, we might remember the terror that Indigenous people in Canada faced when the sweeping epidemics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries left whole communities annihilated. Coming from Europe to “save souls” (and secure natural resources), settlers ended up claiming lives instead—by the tens of thousands. Families were torn asunder by the forced removal of children and adults to quarantine facilities.

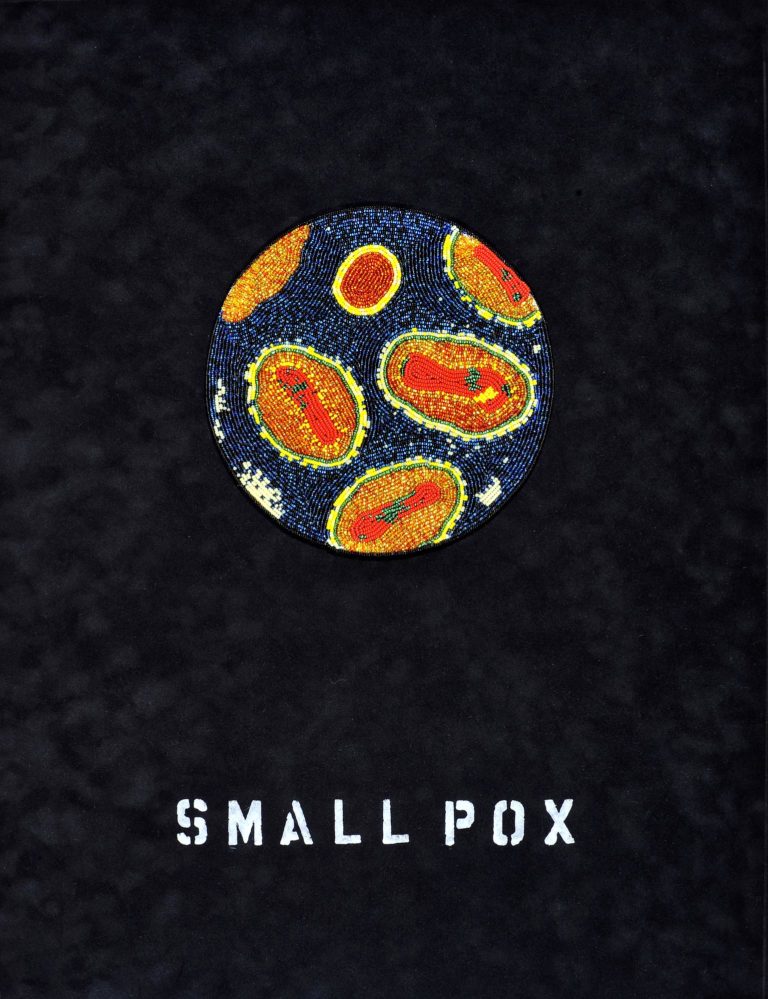

Ruth Cuthand, Smallpox, 2009. Beads and acrylic on suedeboard, 61 x 45.7 cm.

Ruth Cuthand, Smallpox, 2009. Beads and acrylic on suedeboard, 61 x 45.7 cm.

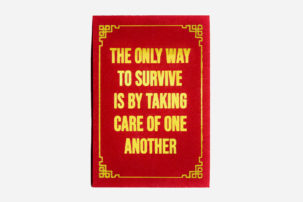

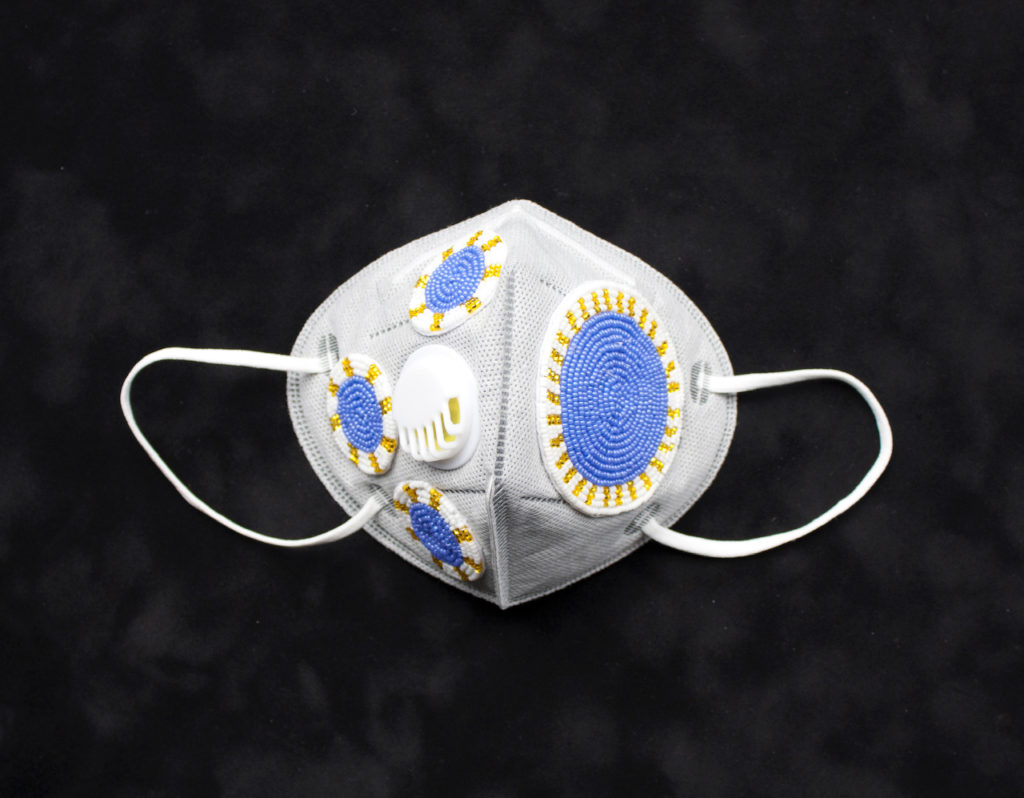

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, mask, thread and backing, 30.4 x 30.4 cm. Courtesy The Gallery/Art Placement Inc.

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, mask, thread and backing, 30.4 x 30.4 cm. Courtesy The Gallery/Art Placement Inc.

More than a decade ago, Ruth Cuthand, a Plains Cree artist born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, found a way to bear witness to these losses. Painstakingly, she beaded the viruses that had claimed so many lives, using as her material that tiny but captivating trade good at the heart of historic Indigenous/settler exchange. In recent weeks, Cuthand has revisited this series in light of the current pandemic and its potential to again decimate remote Indigenous communities. Her work invites us to consider the eerie design of the viral menace, and our human defencelessness before it, memorializing catastrophe and giving a face to a faceless foe.

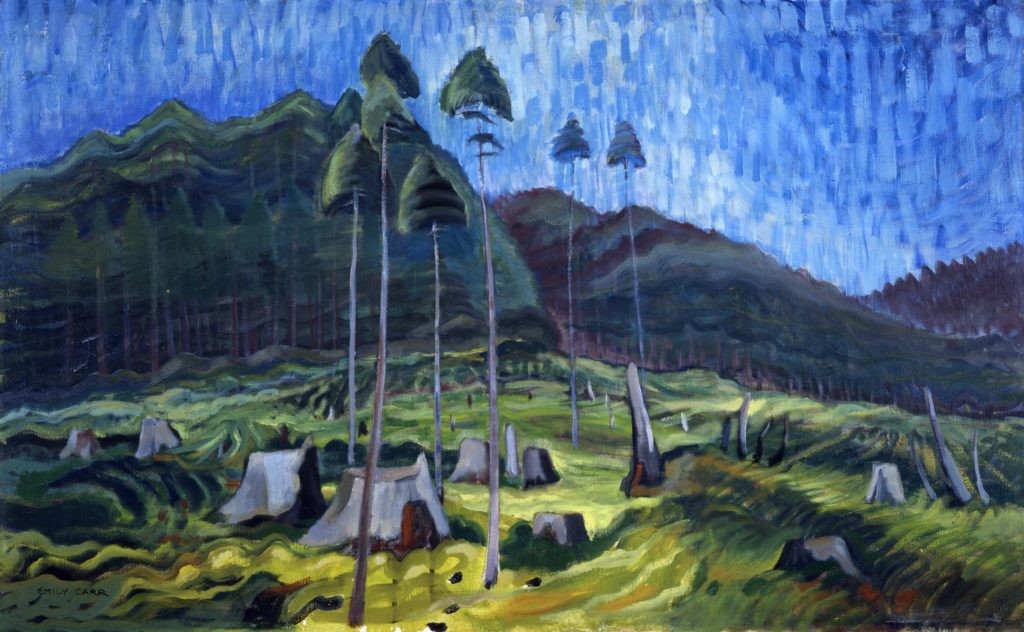

Emily Carr, Odds and Ends, 1939. Oil on canvas, 67 x 109 cm. Collection Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Emily Carr, Odds and Ends, 1939. Oil on canvas, 67 x 109 cm. Collection Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

One of the enduring subjects of Emily Carr’s later years was the cycle of life and death in the forest, with the artist often picturing the undergrowth surging back after the devastation of clearcutting. Sweeping skies and undulating forests show aging trees against a foreground of new growth. Carr, who was raised a Christian of the “All Things Bright and Beautiful” persuasion in Victoria, British Columbia, enjoyed a deep faith in the power of nature to renew itself, despite the onslaughts of humankind. These days, as we watch online videos of dolphins in Italian industrial harbours and wild goats roaming the streets of Welsh coastal villages, we can extract a thread of silver lining from the mayhem. In the silence and sudden vacancy created by quarantine, nature is taking back from us what has always been its due. In downtown Toronto, we can see stars at night.

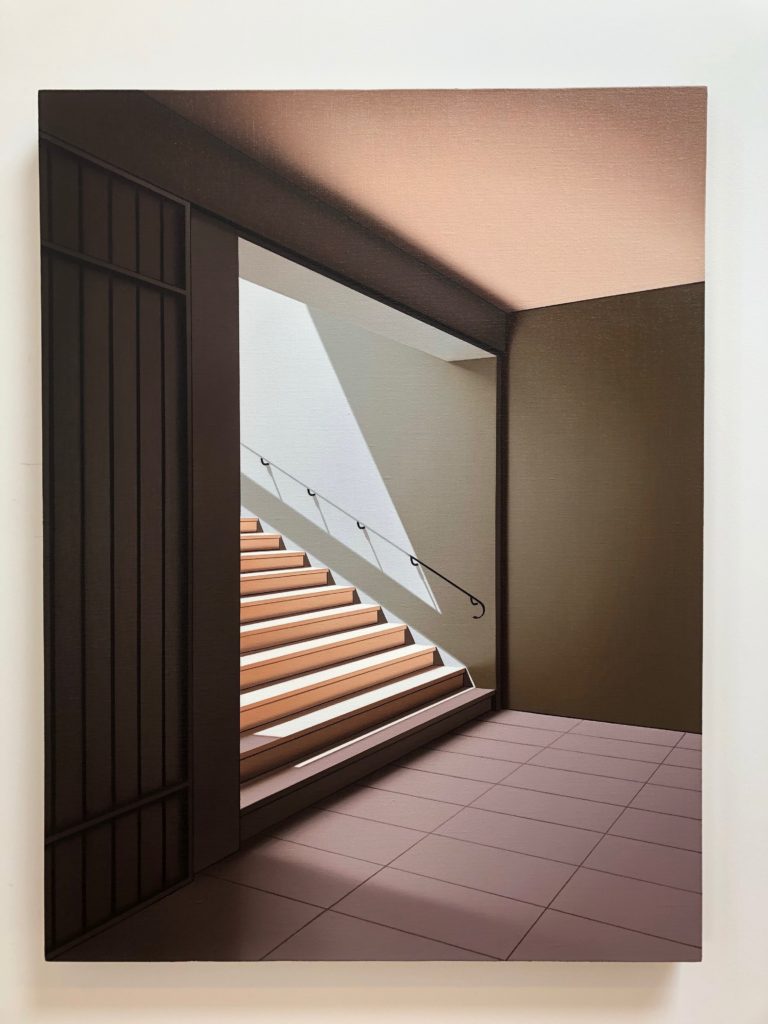

Pierre Dorion, Lisbonne III, 2020. Oil on linen canvas, 83.8 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy Galerie René Blouin.

Pierre Dorion, Lisbonne III, 2020. Oil on linen canvas, 83.8 x 63.5 cm. Courtesy Galerie René Blouin.

Like many people living in northern climates, Canadians are acutely sensitive to the shifting of the seasons; the return of light and warmth in the spring is usually the stuff of ecstatic celebration after so many months of cold and darkness. This spring, it is both light and dark, as we look out the window at the lightening of days, yet hold ourselves in check. This painting, from Ottawa-born, Montreal-based artist Pierre Dorion, with its exquisite depiction of light spilling down the empty stairwell of a Lisbon subway station, evokes a sense of pleasure deferred. We can see the light but we cannot yet feel it, or be in it. Fresh air and wind and other people are, for the most part, to be found elsewhere, just out of reach—at least for now.

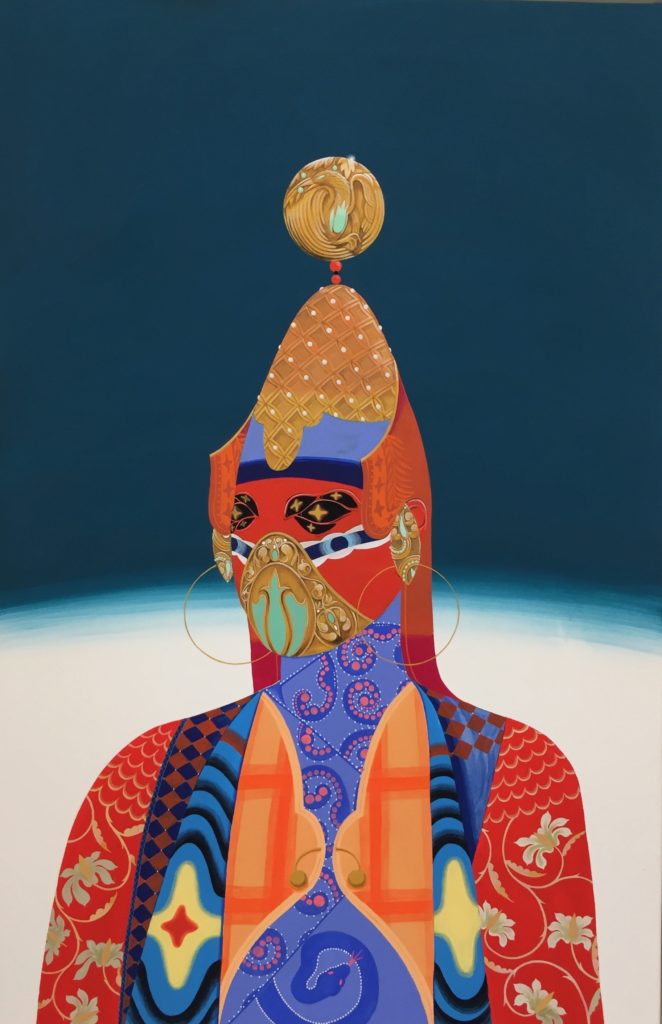

Rajni Perera, Traveller 1, 2018. Mixed media on stretched paper, 58.4 x 90 cm. Courtesy Patel Brown.

Rajni Perera, Traveller 1, 2018. Mixed media on stretched paper, 58.4 x 90 cm. Courtesy Patel Brown.

Toronto artist Rajni Perera has imagined the future, and it is female. Her goddesses are ready for any environmental inclemency. They have evolved multiple eyes, for heightened perception, as well as elaborate facial adornments the better to keep out toxic threat. Born in Sri Lanka, Perera came to Canada as a child, and she carries within her the rich decorative legacy of her family’s culture. But while her motifs recall the patterns of traditional textiles and adornment, her empowered female figures are bracing for the future, seeing it and adapting to it while the rest of us are just catching up.

Brenda Draney, Admitted, 2019. Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 63.5 cm.

Brenda Draney, Admitted, 2019. Oil on canvas, 50.8 x 63.5 cm.

Edmonton artist Brenda Draney, who is Cree from the Sawridge First Nation, knows a thing or two about hospitals. A few years back, her mother had quadruple bypass surgery. A year or so later, her partner was admitted to hospital for treatment of a kidney stone. In both instances, Draney was at their side. (Both her mother and her partner survived.) Reflecting on these experiences, she produced an exhibition of works titled “Smelling Salts.” Her painting Admitted, from this series, records her partner at the hospital. Today, this intimate connection with the afflicted looks like a luxury. Thousands are now unable to accompany their loved ones stricken by COVID-19 as they face their fates. “For so many hours you just memorize their face and their hands and their skin,” Draney told me, remembering her days spent at the bedside. “You say: that’s my loved one. You look for the changes. Their skin looks more sallow. They seem to have lost weight. They seem to have gained weight. You watch. What is painting but empathy with the artist’s hand.”

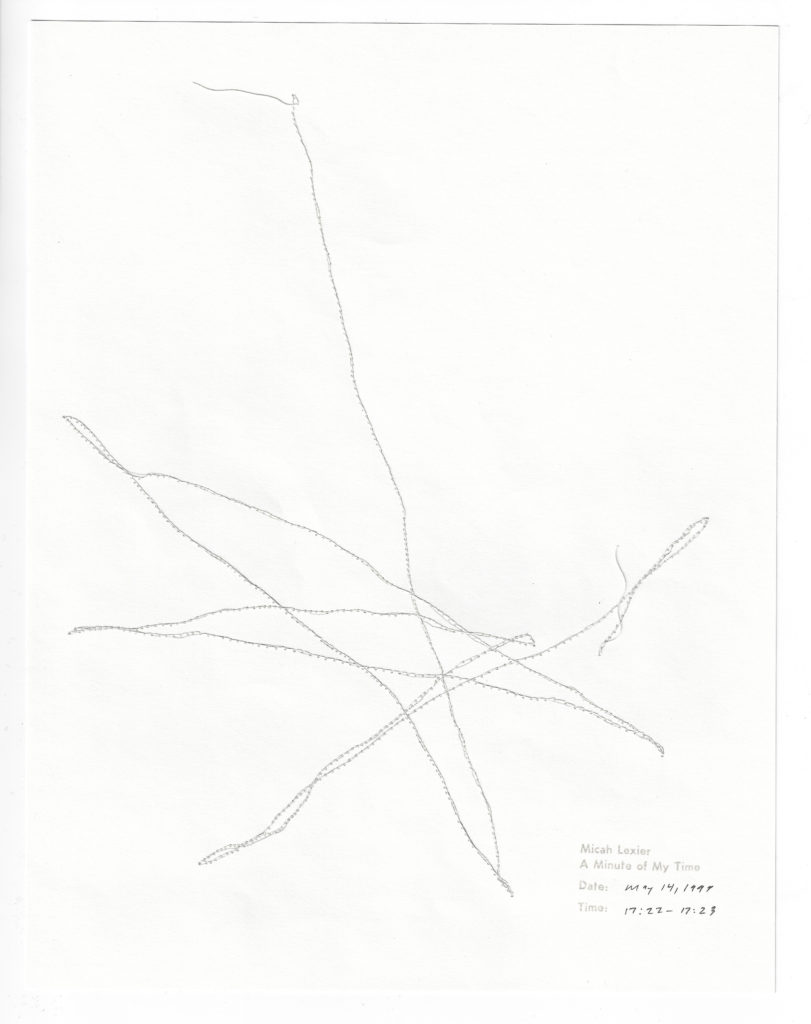

Micah Lexier, A Minute of My Time (May 14, 1999 17:22 – 17:23), 1999. Paper, thread, pencil and rubber stamped ink, 21.5 x 27.9 cm. Courtesy Birch Contemporary.

Micah Lexier, A Minute of My Time (May 14, 1999 17:22 – 17:23), 1999. Paper, thread, pencil and rubber stamped ink, 21.5 x 27.9 cm. Courtesy Birch Contemporary.

We work from home, we keep up with friends and family, we Zoom, we scan the news, but even after all that, many of us have more unscheduled time than we are used to. A phone call need not be so rushed. A walk with the dog can take a little longer. We can read the extra chapter before we turn off the light. Micah Lexier’s work has always paid homage to time, frequently focusing on that modest increment we call the minute. In one series of works, titled A Minute of My Time, Lexier—who was born in Winnipeg and has long lived in Toronto—made a series of scribble drawings that took precisely one minute to complete. Some works from the series exist as graphite drawings, some show the operations of a sewing machine and white thread on a sheet of paper, and others are flame-cut from a sheet of steel and presented in sculptural form. One thing unites them all: the honouring of the humble unit of time we so take for granted, and the rumination on what can best be done with it.

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, mask, thread and backing, 30.4 x 30.4 cm.

Courtesy The Gallery/Art Placement Inc.

Ruth Cuthand, Surviving: COVID-19, 2020. Glass beads, mask, thread and backing, 30.4 x 30.4 cm.

Courtesy The Gallery/Art Placement Inc.