In a 21st-century city, it is easy to feel simultaneously surrounded and alone. If it is impossible to find refuge—and it might be—we might also be able to make a little space. In much of the urban settings stamped with the label “global city,” square footage is expensive; that is something everybody knows because they live it. In midtown Manhattan, people flock from all over the world to work, to vacation, to go to a museum or a library, to shop, to beg for change.

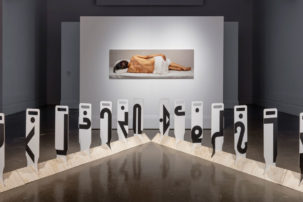

What do you call the emotional landscape of midtown, a place to which no one necessarily really belongs? At 36th Street and Madison Avenue—some call this east-side neighbourhood Murray Hill—is The Morgan Library and Museum, which recently showed “Speed of Life,” a travelling retrospective exhibition on the American photographer Peter Hujar. Previously shown in Barcelona and The Hague, the show will travel to the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

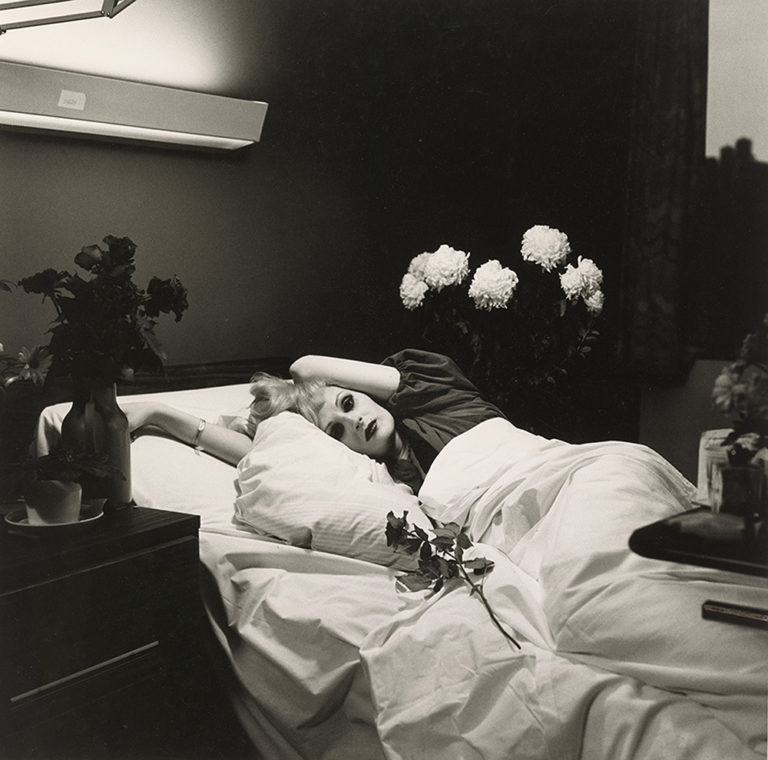

Hujar, Peter,Candy Darling on her Deathbed, 1973. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Collection Ronay and Richard Menschel. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Hujar, Peter,Candy Darling on her Deathbed, 1973. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Collection Ronay and Richard Menschel. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Hujar was born in 1934 in Trenton, New Jersey; he moved to Manhattan when he was 12, later became canonized alongside photographers Diane Arbus and Robert Mapplethorpe, and died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987. (Of course, the crisis era of HIV and AIDS would further historicize the date of his death.) Hujar said that his work encompassed “uncomplicated, direct photographs of complicated and difficult subjects.” When Hujar worked out of his East Village studio, downtown Manhattan was also a complicated and difficult space. It still is, albeit in different ways. Hujar’s photographs are thick—with history, and tone.

If the Morgan doesn’t exactly feel like a museum, that’s because, historically, it was not. It was a gift to the public: American executive J.P. Morgan Jr., who financed much of World War I, transformed the private library of rare items of his banker father, John Piermont Morgan Sr., into a museum institution. This monied history makes the palatial setting of the contemporary Morgan Library feel haunted. It’s beautiful, with a garden courtyard, and a three-tiered library with walnut bookshelves, a red study reminiscent of the textures in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and decorative ceilings. Much of the decor is styled in the bombastic patriotism of American Renaissance aesthetics.

Those who strain to tell the official history of the dispossessed, such as the exhibition’s curator Joel Smith, as well as the reviewer in The New York Times, emphasize the location of it all: Hujar’s studio in the Lower East Side/East Village. The first sentence of the wall text reads, “The life and art of Peter Hujar (1934–1987) were rooted in downtown New York.” Still, sometimes, in the heat of it all, we forget that New York has insides, that space has an interior life amid its architecture and urban planning schemes. For Hujar, the interior is not a metaphor for private life. Instead, insides denote a terrible beauty, an impossibility that must be documented.

When you enter the exhibition, that difficult and complicated space of Manhattan is put on pause by the roomy grandeur of The Morgan’s architecture. Hujar’s portraits themselves threaten to slow down the frenetic speed of midtown Manhattan, evoking a community of strangers through averted gazes, long stares and stunted lives.

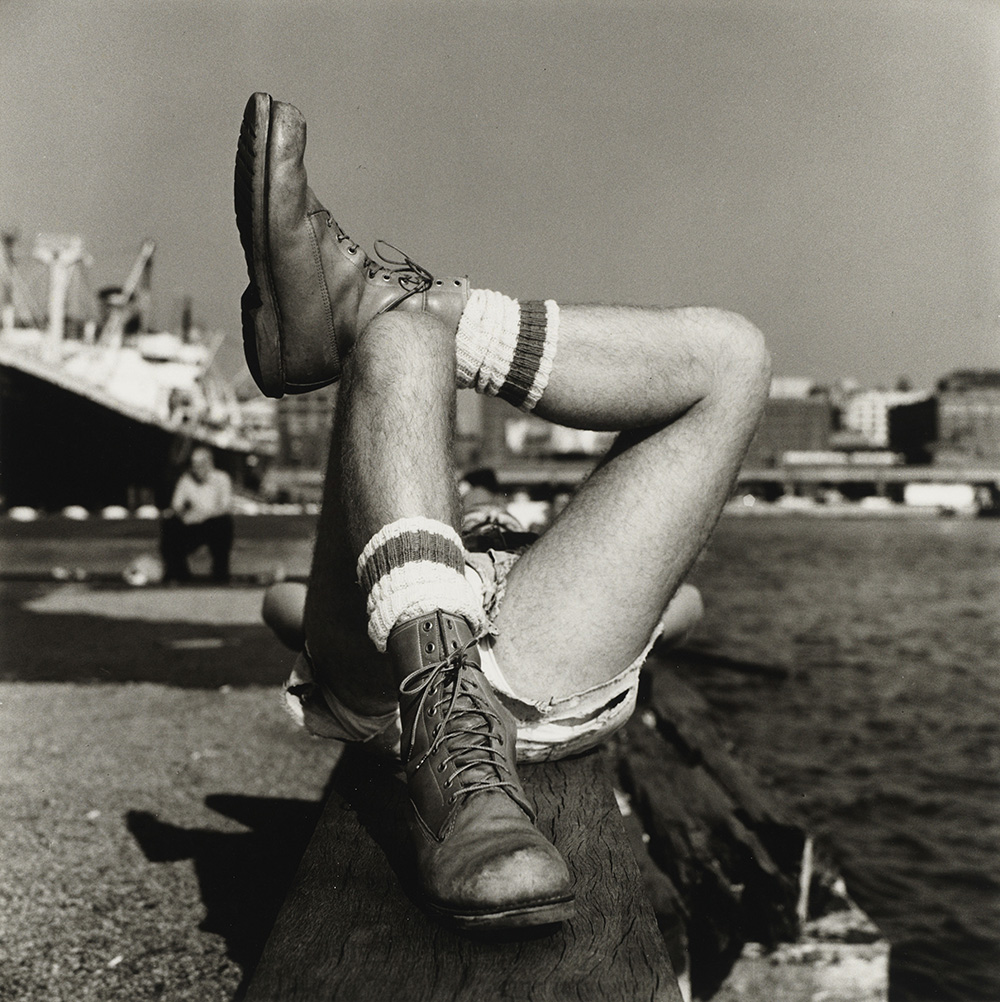

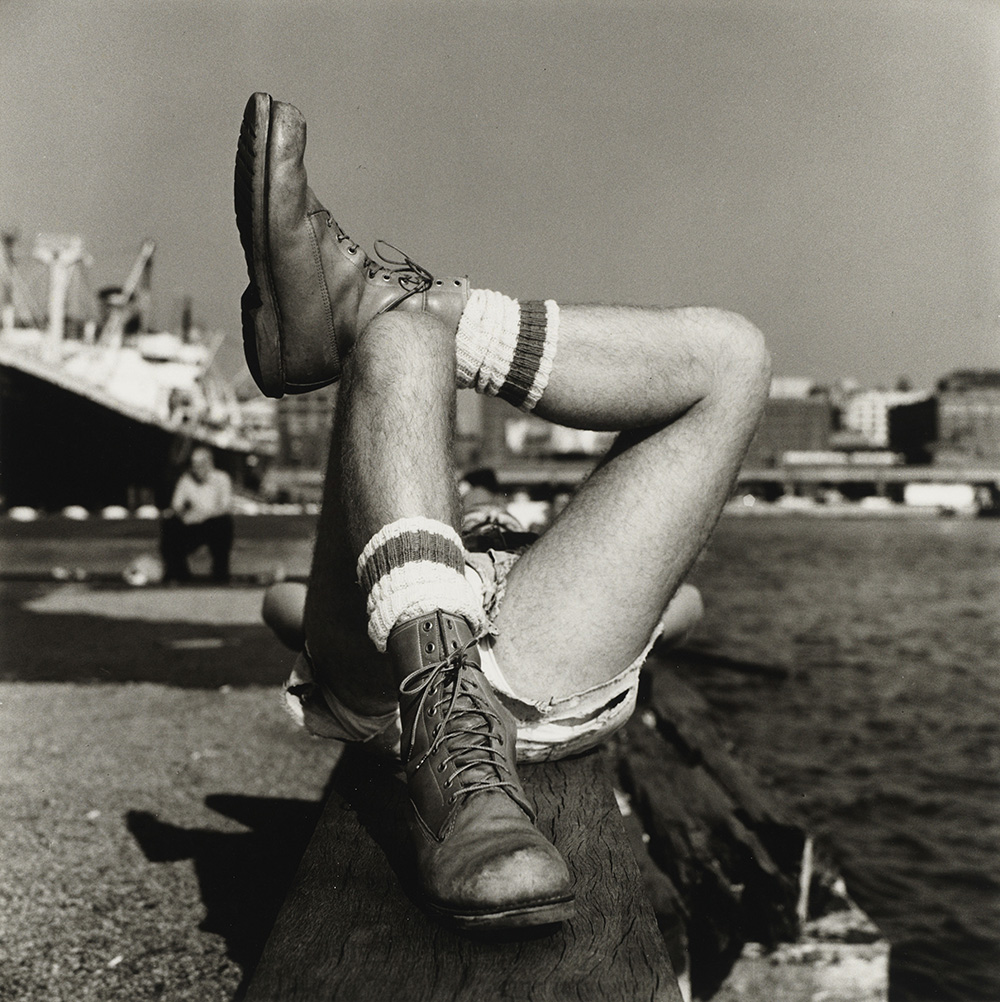

The room that houses “Speed of Life” overflows with Hujar’s photographs, inscribing itself on the many locations in which Hujar shot. In a sense there are more photographs than area. In this show, there are 164, to be exact. And each black-and-white portrait, what Hujar was known for, references some interior of life and space. While some of the photographs capture the outdoors—a garden in Sicily; cows in a field; a Gay Liberation Front march; an anonymized surf; the Christopher Street piers; the World Trade Center at nightfall—it is inside where it hurts.

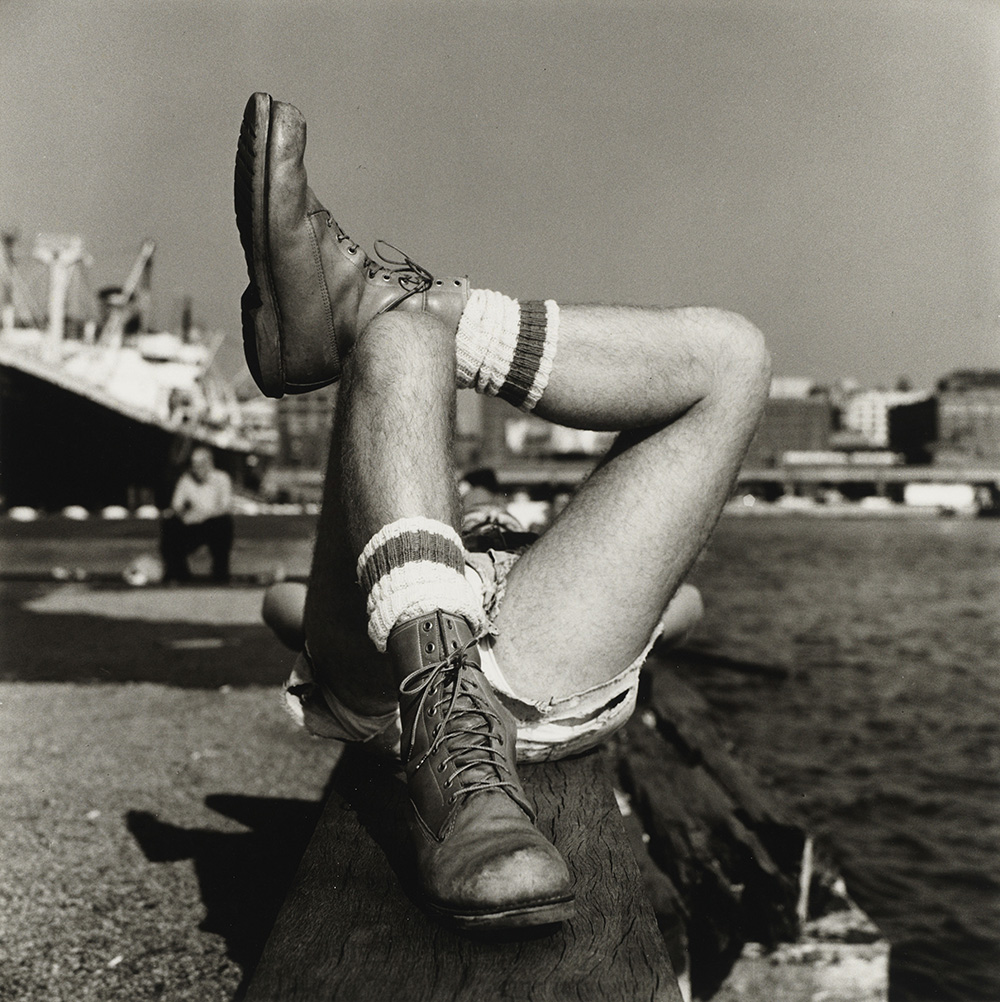

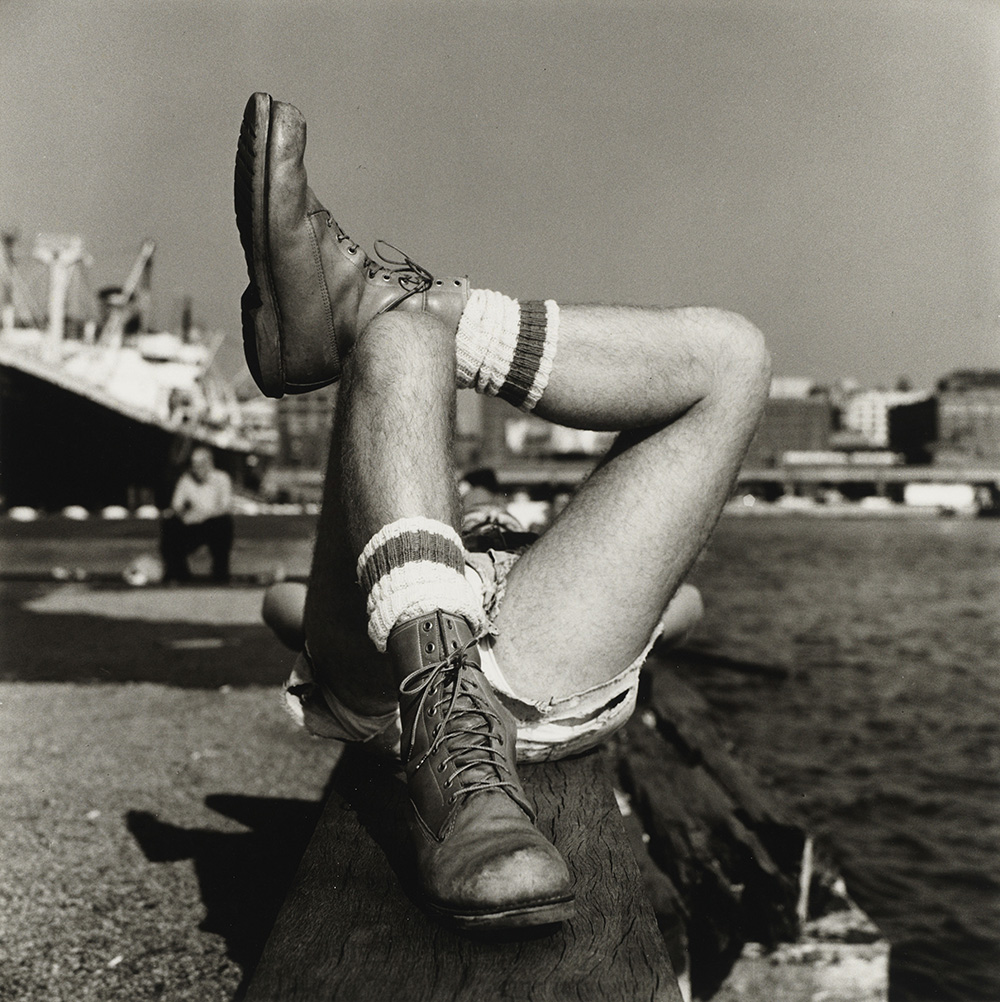

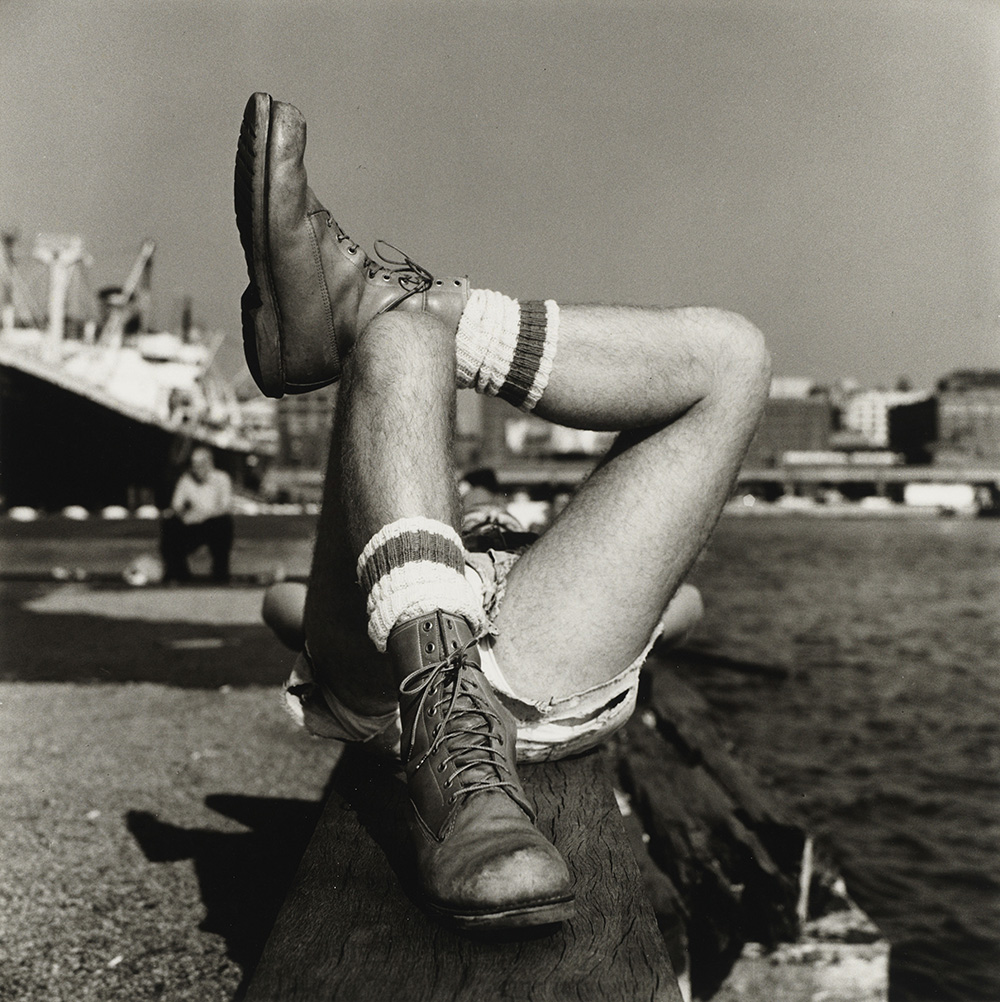

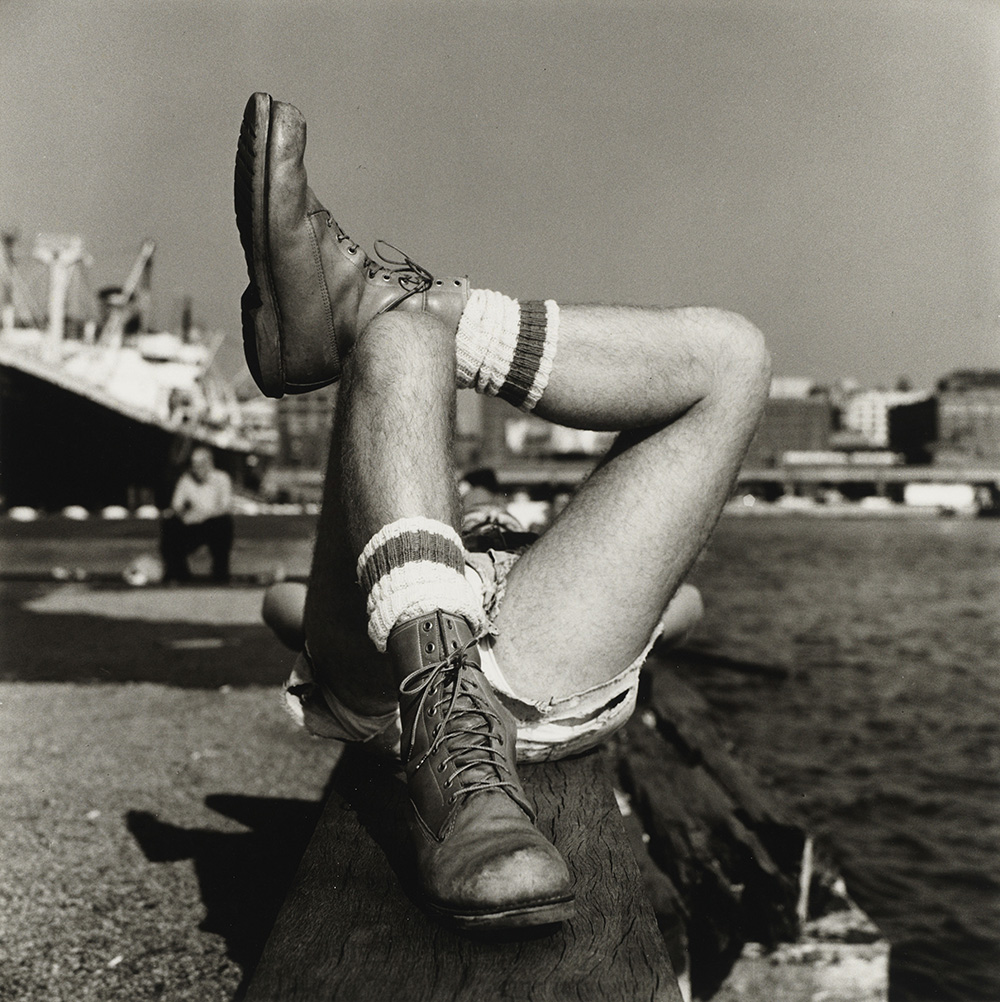

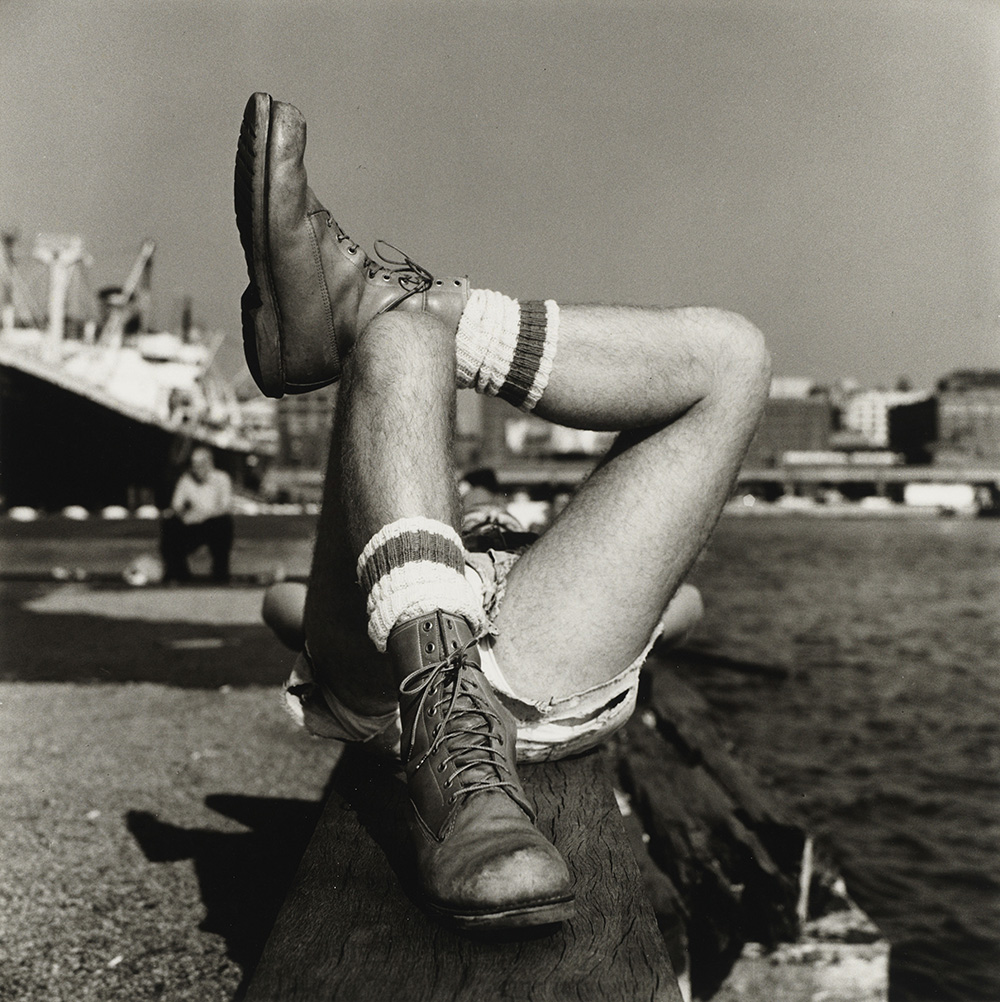

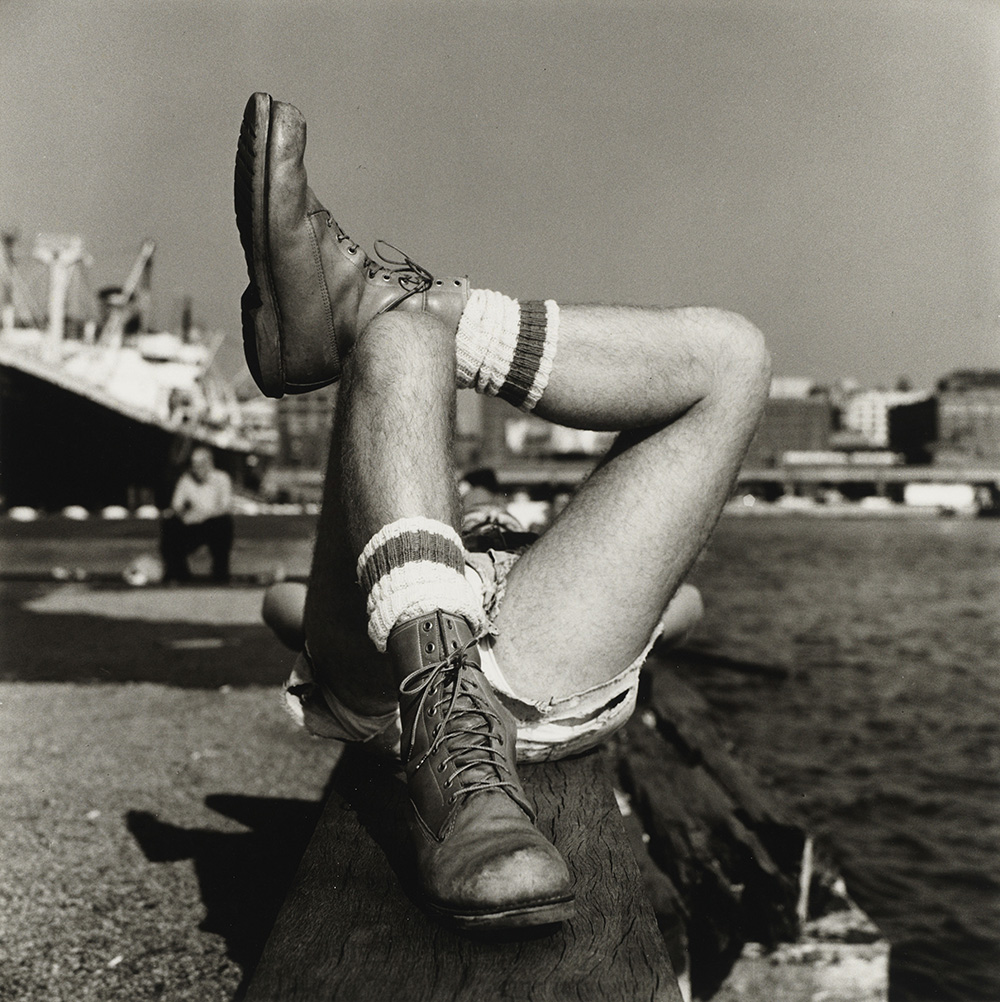

Hujar, Peter, Christopher Street Pier, 1976. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Hujar, Peter, Hudson River, 1975. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Peter Hujar, Horse in West Virginia Mountains, 1969. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Collection of Ronay and Richard Menschel. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Susan Sontag, 1975. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Gay Liberation Front Poster Image, 1969. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Greer Lankton, 1983. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Gary Indiana Veiled, 1981. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Gary Schneider in Contortion, 1979. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Ethyl Eichelberger as Minnie the Maid, 1981. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Peter Hujar, Daisy Aldan, June 19, 1955. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

Peter Hujar, Boy on Raft, 1978. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. ©Peter Hujar Archive, LLC.

In a piece in Harper’s, the director of Hujar’s archive, Stephen Koch, recently wrote something that is hard to forget: “The camera was Peter’s instrument of intimacy. Its lens gave him something he could not otherwise achieve and could not live without: an equilibrium between closeness and distance. He also believed that the camera could reveal things that were invisible to the naked eye. It could show the evidence of people’s inner lives on their bodies and faces, and how they lived in the moment, how they were or were not fully themselves.”

What about a city’s inner lives?

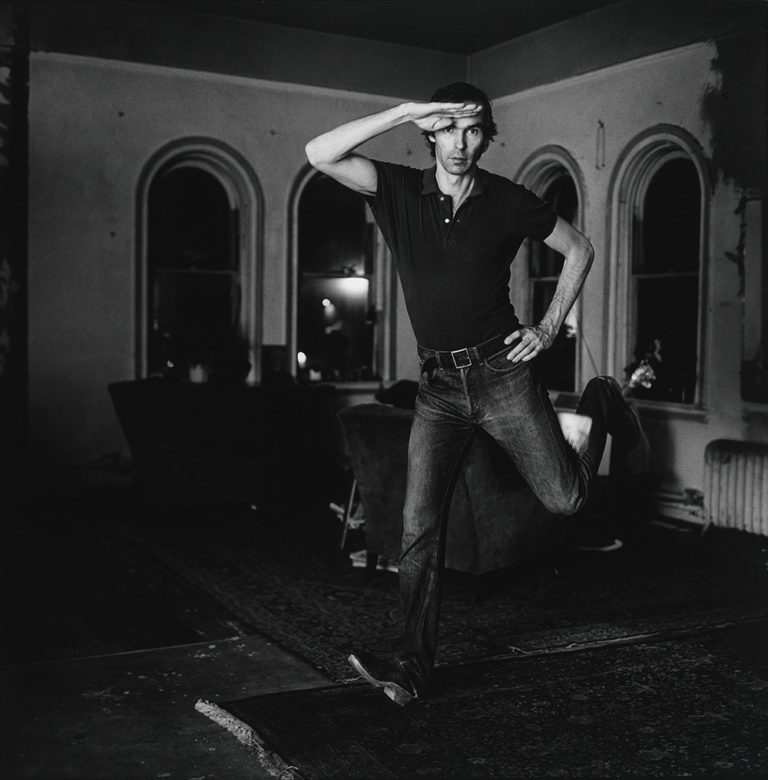

Peter Hujar, Self-Portrait Jumping, 1974. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Peter Hujar, Self-Portrait Jumping, 1974. Gelatin silver print. Purchased on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum, 2013. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Portraits compel us to focus on great people—the Candy Darlings and Susan Sontags of the world, as if there could be a plural—but portraits can’t represent their supposed foregrounds, the figure, without representing their backgrounds. In an early 1957 portrait, Paul Thek, Coral Gables, Florida, the eponymous artist and friend of Hujar’s takes up at most a third of the image: he is seated in a chair, his head positioned in profile, with a stern gaze, a rested arm, a crossed leg. The rest is light and dark: a whited-out window punctuated by a tall, leafy plant that hangs over Thek’s head like rain.

The same year: Cat on Cash Register. In pounce position, a cat looks straight at the camera, encircled by bottles of wine and liquor. The interior here feels like ripped-out guts—an internal necessity that has showed up in entirely the wrong place.

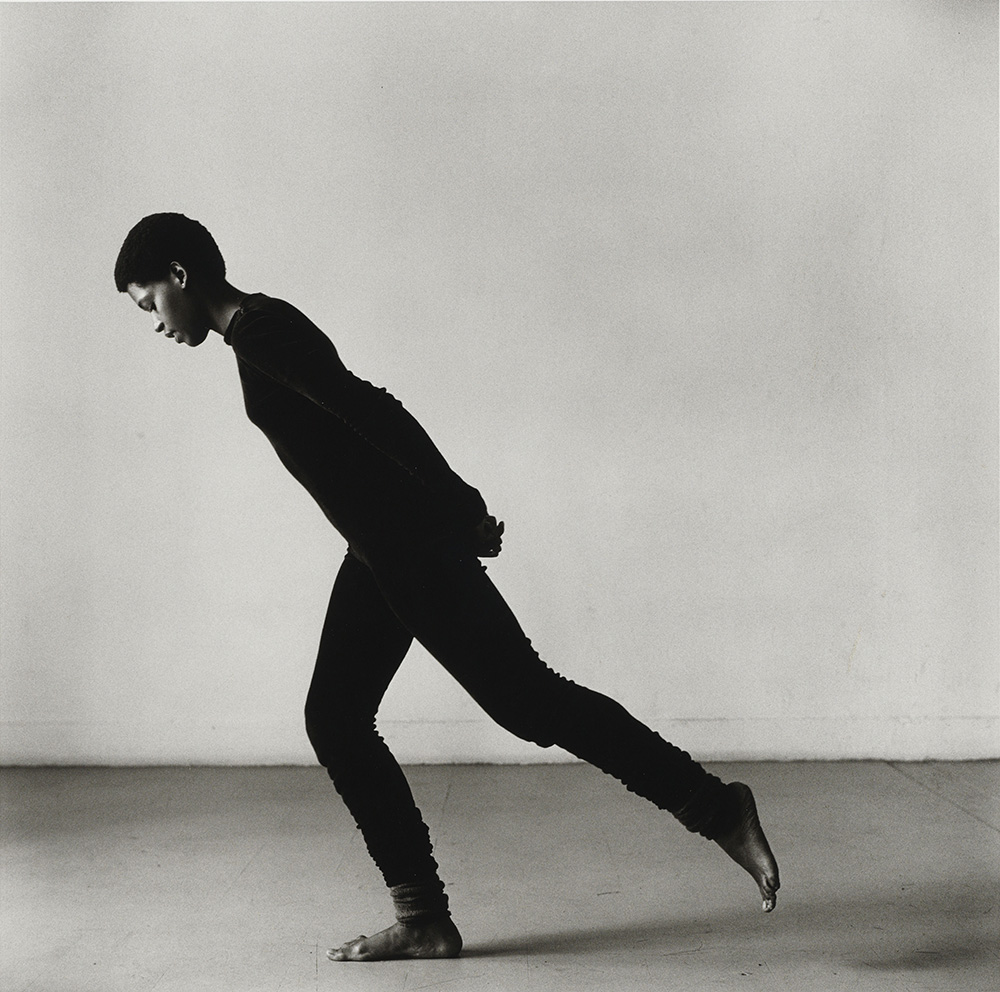

Then there are the canonized shapes Hujar marked. There are the diagonal compositions, which the curators group together in a quartet—Stromboli (1963); Bouche Walker (Reggie’s Dog) (1981); Dana Reitz’s Legs, Walking (1979), Sheryl Sutton (1977)—and in which, as told by the didactic panel, “a line guides the eye from the top left to the bottom right of the frame.” Or the reclining portraits, of Susan Sontag, or Candy Darling glamorized on her deathbed, or the famous one of Fran Lebowitz in bed at her home in Morristown, New Jersey in 1974.

In the 1980s, the shadows get darker, the contrasts deeper. There’s Ethyl Eichelberger Applying Makeup (1982) or Hall, Canal Street Pier (1983), a photograph of a dilapidated hallway gesturing to a place where people—squatters—came together. This is an image set against the backdrop of the AIDS crisis, and its landscape of neglect.

Hujar himself never liked to interpret his own work. In an interview with David Wojnarowicz from the early 1980s, he famously said, “One thing I won’t answer is anything about why I do what I do.” Hujar knew intimately that interpretation often seizes the object it attempts to give meaning to.

Peter Hujar, Sheryl Sutton, 1977. Gelatin silver print. Purchased

on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar

Archive, LLC.

Peter Hujar, Sheryl Sutton, 1977. Gelatin silver print. Purchased

on the Charina Endowment Fund, the Morgan Library and Museum. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York/Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. © Peter Hujar

Archive, LLC.