What do Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur have in common? They both appear in an artwork by the late Panchal Mansaram, a Canadian artist born in India and an Indian artist who spent most of his life in Canada. P.Mansaram (he liked to write his name without a space) defied the hyphenated ways we understand the work and experiences of diasporic artists. Indeed, hyphens have never sufficed to reflect the lives of artists who have crossed borders. Literal movement has always been matched by conceptual movement, metaphorical movement, emotional movement and psychological movement. This was certainly the case with P.Mansaram, an artist whose diasporic experiences were reflected not only in what he made art about, but also how he approached medium, technique and form.

P.Mansaram passed away in December 2020 at 86 years old from natural causes, just as his work was gaining recognition among a wider Canadian contemporary art audience. This late recognition is largely thanks to the exhibition “The Medium is the Medium is the Medium,” curated by Indu Vashist and Toleen Touq of the South Asian Visual Arts Centre (SAVAC), at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in 2019 and the Art Gallery of Burlington in 2020. Over the years, he had solo exhibitions at the Art Gallery of Mississauga, Ed Video Media Arts Centre in Guelph, the Art Gallery of Hamilton and the South Asian Gallery of Art in Oakville, to name only a few that I saw personally in the past 15 years. And yet these other shows didn’t quite achieve the same profile. Is this because they were in suburban locations? Or is it because an awakening to P.Mansaram’s work can be attributed to an art scene that seems more open now? Maybe it’s a bit of both; but what seems clear is that for a long time, artists living and exhibiting outside of downtown cores—who have largely been artists of colour—did not have the same visibility as those in urban centres. These systemic barriers have created certain patterns of visibility and invisibility that, it seems, have only recently started to shift. Nonetheless, what I do know is that P.Mansaram is receiving recognition now not because he has finally caught up to the art world, but because we have finally caught up with him.

P.Mansaram, Ravana in a snowy backyard, 1986. Xerox cut-out on gelatin silver print, 28 x 35.5 cm. ROM 2015.75.30. Gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Ravana in a snowy backyard, 1986. Xerox cut-out on gelatin silver print, 28 x 35.5 cm. ROM 2015.75.30. Gift of the artist.

I met P.Mansaram soon after joining the Royal Ontario Museum as a curator in 2002. He reached out to me, and soon enough I was making periodic trips to Burlington, where he lived, to see the recent art he had made, talk about the Indian art world and enjoy the company and cooking of his wife, Tarunika, who was also an artist. He could talk, and he had many stories of the artists he interacted with, the different periods in his life and how his trust in the divine would take care of his path forward. I am grateful now for this time and the opportunity to interview him formally and informally. During that time, I acquired his work for the Royal Ontario Museum’s collection and, from 2014 to 2017, brought in more than 700 artworks (including boxes of archival material that we are still processing) representing every period in his artistic practice. What attracted me to the work and his story was how it offered something unique about both the way diasporic artists speak many visual languages and the new ways we can understand global modernism from a Canadian perspective. P.Mansaram was a stickler for accuracy, so this essay is an attempt to put down some markers about his art practice, confirmed by him through successive conversations, so that others may explore his work.

P.Mansaram was born in 1934 in Mount Abu, Rajasthan, on the western side of India, during a time when parts of India were a British colony. Mount Abu was an old pilgrimage town, known for its syncretic culture and ornate marble temples dating back a thousand years. According to P.Mansaram, it was also a colonial town, and his father looked after some of the newer buildings. It had wide roads and was one of the first places in British India to have filtered water piped into homes. P.Mansaram didn’t remember being aware as a child of the Partition of 1947, which marked independence from colonial rule and also the displacement of millions of people from their homes due to the violence that accompanied the births of Pakistan and India. But what he did remember from this time was losing much of his immediate family to an epidemic of typhoid, an experience that led him to seek comfort in nature and the cinema.

P.Mansaram, Sequence of Life, from the series Impressions of Nepal, 1959. Acrylic on paper, 65 x 49 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Sequence of Life, from the series Impressions of Nepal, 1959. Acrylic on paper, 65 x 49 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

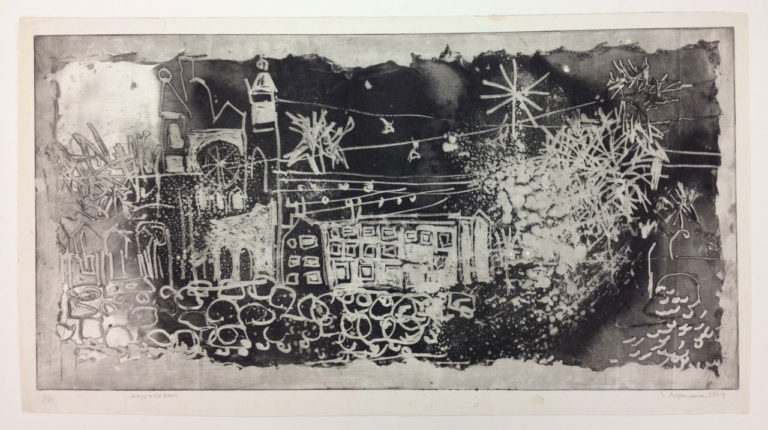

P.Mansaram, Amsterdam, 1964. Etching, 40 x 72.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Amsterdam, 1964. Etching, 40 x 72.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

His father was not happy when P.Mansaram, the eldest surviving son in the family, announced he wanted to study art, but he was permitted to go if he made his own way. From 1954 to 1959, P.Mansaram attended the Sir J.J. School of Art, a colonial institution in Mumbai that became a generative space in the post-colony for a new crop of artists. There he took classes on life drawing alongside visits to Indian heritage sites. By the time he graduated, he had won several awards—including a gold medal he later sold for cash to support himself—and was hired by Pupul Jayakar and K.G. Subramanyan, leaders in the postcolonial revival of traditional arts, to work as a designer in the Weavers’ Service Centre in Kolkata. To support himself, he also worked as an illustrator for the Times of India, an experience that allowed him to travel on assignment and meet prominent artists like M.F. Hussain and the filmmaker Satyajit Ray. Art historian Geeta Kapur has explained, in When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (2000), that, unlike Western modernism that decisively broke with the past, Indian modernism was an anti-colonial gesture that embraced a pre-colonial past as a way to invent a new modern art. In this way, P.Mansaram was part of an art scene in the process of working through and identifying its own version of modern art.

From the 1960s onward, many Indian artists went abroad to study in art schools across Europe, experiencing what Simone Wille has called a “post-war artistic mobility” that shaped a “transcultural project of modernism.” Between 1963 and 1964, P.Mansaram studied in Amsterdam at the Rijksakademie on a Dutch government fellowship, where he learned printmaking. He also met members of COBRA (or CoBrA) who in their work embraced artistic experimentation, folkloric elements, bold colours and layering of images reminiscent of collage. In particular, the experimentation with printmaking that Mansaram engaged in there led to his interest in mechanical forms of reproduction. While abroad, he also travelled through Western Europe, Greece and Egypt, and was impressed by the mixture of text and image on the ancient art he saw there.

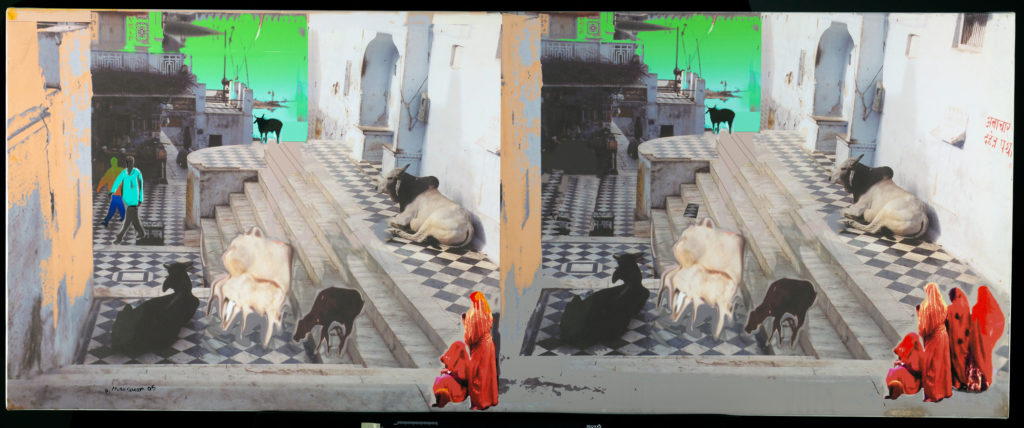

P.Mansaram, Pushkar, 2005. Mansamedia (acrylic enhanced giclée on canvas), 51 x 127 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Pushkar, 2005. Mansamedia (acrylic enhanced giclée on canvas), 51 x 127 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

In semiotics, any text or image is understood as a sign that is ascribed an arbitrary meaning (referent) until it is learned by a group of people and becomes a system of communication. Signs encountered by new groups of people are often “lost in translation” or illegible or simply not recognized as signs until the code is learned. P.Mansaram’s early experiences travelling around the world led him to learn different cultural codes, not as a way to reproduce them, but rather as a way to unmoor himself from any particular one. It is as though he was able to detach the sign from its referent, but still love it and work with it anyway. This is one of the reasons his work focuses on the medium and a practice of repetition, as Vashist and Touq have pointed out. His diasporic experience gave him a distanced eye to observe the world around him—at once inside and outside, local and global.

Back in Delhi, two important things happened. P.Mansaram met George Butcher, a young Oxford University student studying Indian modern and folk art who left his studies to become a dealer and art critic, later moving to Canada and who, P.Mansaram once told me, was involved in the Indian Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal. According to the Critical Collective (an online portal for the study of Indian art) and Asia Art Archive, Butcher spent 28 months in India “[putting] together works of Indian artists alongside folk art, popular material like hand-painted signs and traditional toys.” His gallery in Montreal was one of the gateways for Indian objects to enter a Canadian market, and his influence on the public/scholarly interest in the folk and modern art of India has still to be fully understood. The other thing was that the immigration arm of the Canadian Embassy moved a few doors down from P.Mansaram’s home in Delhi. He applied for a Canadian visa, and in July 1966 moved to Canada with his wife, Tarunika, and three-month-old daughter, Mila.

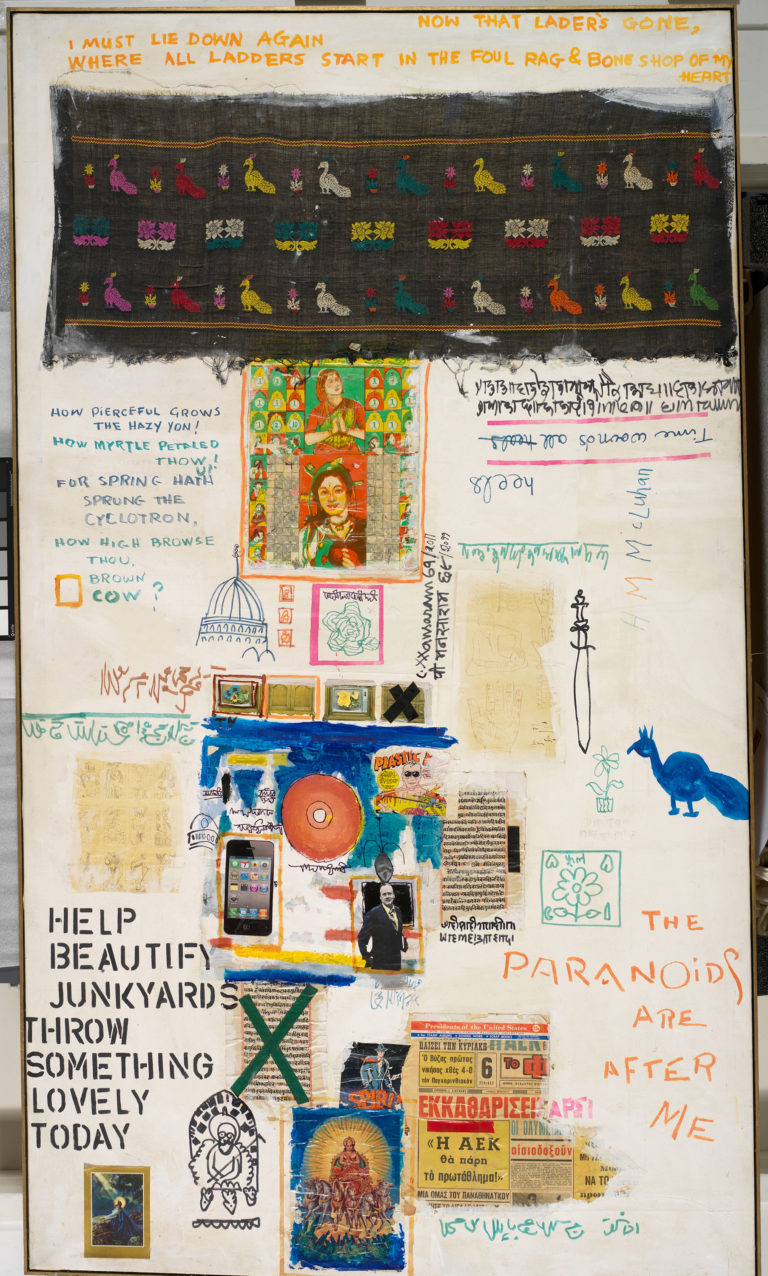

P.Mansaram in collaboration with Marshal McLuhan, Rear View Mirror #74, 1969/2011. Mixed-media collage with fabric, paper, marker and acrylic on board, 198 x 112 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection.

P.Mansaram in collaboration with Marshal McLuhan, Rear View Mirror #74, 1969/2011. Mixed-media collage with fabric, paper, marker and acrylic on board, 198 x 112 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection.

P.Mansaram, Kissing Movies (Rear View Mirror #59), c. 1973. Mixed-media collage with lenticular print on board, 61 x 61 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Kissing Movies (Rear View Mirror #59), c. 1973. Mixed-media collage with lenticular print on board, 61 x 61 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

Upon arrival in Canada, first in Montreal and then Toronto, Mansaram reached out to Marshall McLuhan, to whom he had previously written after being impressed by a LIFE magazine article about him. McLuhan (1911–1980) was a professor at the University of Toronto whose work has been a cornerstone for the study of media theory, and who coined the phrase “the medium is the message.” Mansaram and McLuhan forged a friendship based on a synergy of ideas that would last throughout their lives. They worked together on several projects, as Alexander Kuskis has written: P.Mansaram designed collage artwork that was reproduced on the covers of McLuhan’s two-volume anthology for high schools, titled Voices of Literature; McLuhan invited P.Mansaram to run workshops during his public Monday night seminars; and P.Mansaram collaborated with McLuhan on “East-West Intersect,” a “happening” and related film screening at Isaacs Gallery, a location which was at the forefront of the Toronto art scene from the 1950s through the 1980s. From the late 1960s onward, P.Mansaram produced a series of collage works called Rear View Mirror; these were inspired by McLuhan’s writings which likened the experience of being in a media-saturated culture with seeing the world through small fragments moving by, as one might through a rear-view mirror. Rear View Mirror #74 (1969/2011) was a collaborative work where P.Mansaram applied paint and images and McLuhan added text, commenting on popular culture and mass media. In 2011, P.Mansaram further modified the work by adding images of a CD-ROM and iPhone as a way to bring it up to the present day.

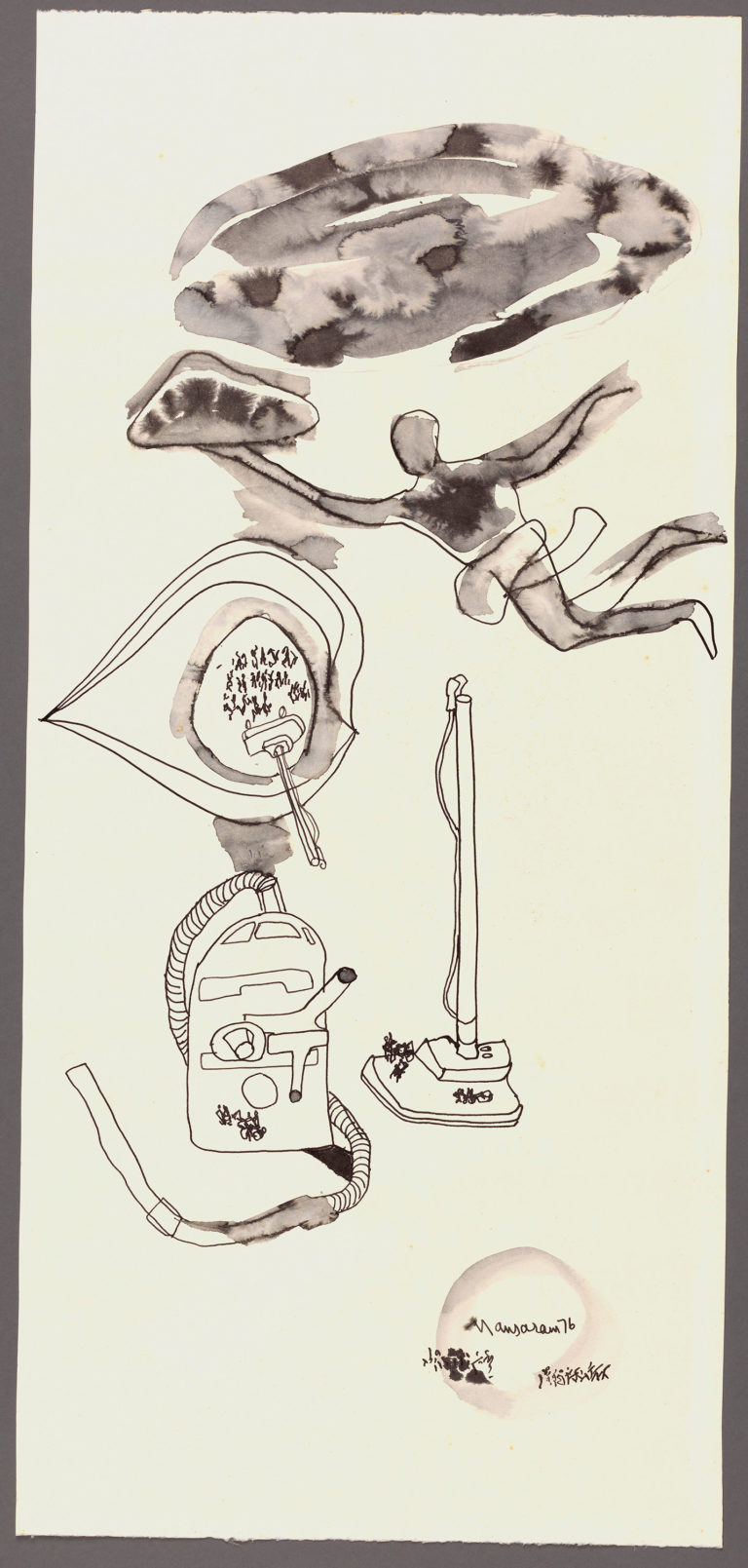

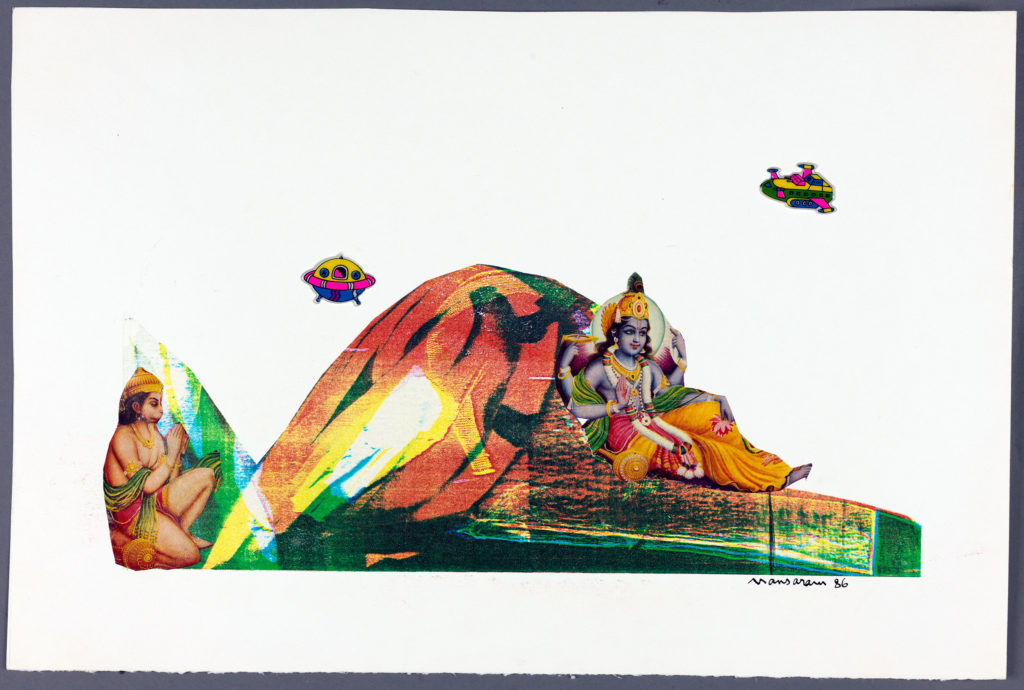

P.Mansaram considered everything collage—nature, media, life—and approached it as a form of documentation and play. Little puffy-sticker spaceships flying in a landscape with a figure of the Hindu god Vishnu cut out of a magazine or calendar. A small black and white photocopied print of the multi-headed Ravana glued to a photographic print of an Ontario winter landscape. He pasted doilies, plastic board-game pieces, newspaper ads and pages from a handwritten Sanskrit manuscript onto canvases brushed with acrylic paint. He was attracted to the magical in daily life, which he saw represented in the stories of Hindu gods that he had learned about as a child, and in the new technologies that had eased domestic life and sent people into outer space.

P.Mansaram, Untitled, 1976. Ink on paper, 66 x 30.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Untitled, 1976. Ink on paper, 66 x 30.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

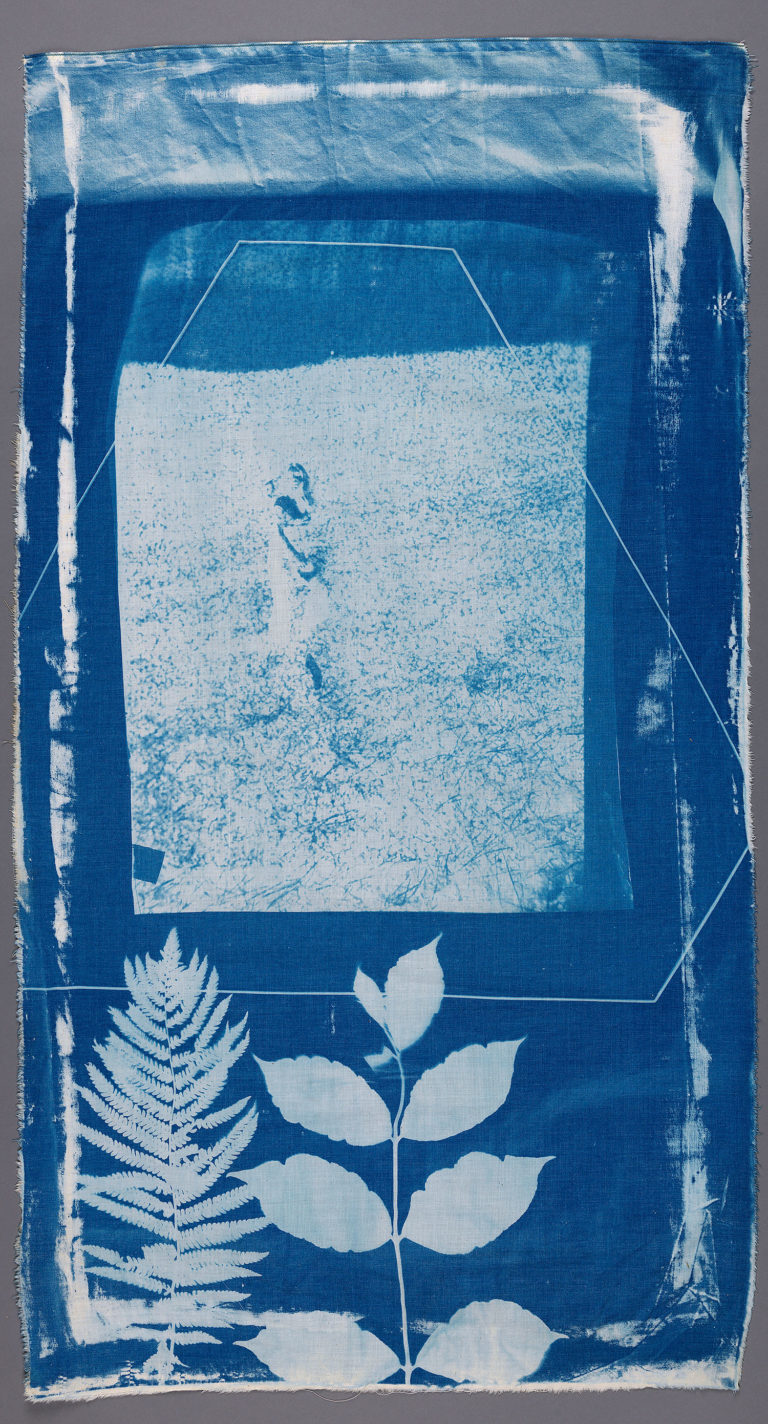

P.Mansaram, Untitled, 1976. Blue print on fabric, 109 x 66 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Untitled, 1976. Blue print on fabric, 109 x 66 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection, gift of the artist.

As a way of supporting his family, P.Mansaram taught art in Hamilton, which he continued to do until he retired in 1989. The 1970s and 1980s were a balance between teaching and continuing his own practice late into the night and on weekends. He participated in numerous group exhibitions around Ontario and abroad including one featuring his Rear View Mirror series that travelled around Atlantic Canada from 1971 to 1972. This was interspersed with annual trips back to India, where he displayed at prominent art galleries like Jehangir, Pundole and Piramal in Mumbai and Dhoomimal in New Delhi. He started working with fabric because it was easier to transport and display without costly shipping and framing. He was attracted to low-cost, low-tech methods including serigraphy, cyanotype, electrostatic colour transfer, xerography and lasergraphy—the choice of a diasporic artist on a budget, one could argue. He even turned a manual credit-card machine into a mini printmaking tool.

Health issues led him to retire early, and he focused his work on nature, making site-specific installations in his backyard and at Mount Abu. In the 1990s and 2000s, he embraced the digital and developed something he called “mansa-media” (or “mansamedia”), his own method for combining printing technologies, collage, digital manipulation and painting in layers so that in the end it was unclear where one method stopped and the other started. Throughout, he also experimented with film. Devi, Stuffed Goat and Pink Cloth (1967) is a series of collage-like impressions of Mumbai in 16 mm. But one of my favourites is the more recent Tea Sipping Man (2012), made for the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival in Mumbai. This short and simple piece captures an extended moment of a man enjoying his afternoon tea; the quiet joy and unselfconscious satisfaction is palpable on his face and in the gesture he makes with his hand, like an uncodified version of abhinaya and mudra from Indian classical dance. It is a cultural code beyond the ability of language to explain; if you know, you know.

P.Mansaram, Vishnu and Hanuman in landscape with spaceships, 1986. Plastic stickers and printed cut-outs on paper, 29.5 x 44.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection. Gift of the artist.

P.Mansaram, Vishnu and Hanuman in landscape with spaceships, 1986. Plastic stickers and printed cut-outs on paper, 29.5 x 44.5 cm. Royal Ontario Museum Collection. Gift of the artist.

Panchal Mansaram is one of the few artists from the South Asian diaspora whose career stretched from before 1980 and into the decades afterwards. Many of his peers from India who settled elsewhere—such as S.H. Raza in Paris and F.N. Souza in New York—have achieved commercial success in India and abroad. Had he stayed in India, P.Mansaram likely would have as well. But the conservative collecting environment in Canada, long geared toward landscape painting, had little room for his art. There was also the added burden of being a brown man in a white space that gave visibility to only certain forms of creativity. I will never forget the story he told me once of finally arranging a meeting with a contemporary art curator at a large art institution in Toronto; on arrival he was not invited into the building. Instead, the curator would only meet him on the sidewalk outside. This was received by P.Mansaram as a slight, an insult, a manifestation of the profound sense of difference he had encountered in Canada. I remember his face when he told me the story: he looked straight ahead with his chin held high, but I could see how painful the memory was. He only ever told me that story once and never mentioned it again. Since then, I have pondered this silence. It feels familiar to me, especially among South Asian immigrants of a certain generation who perceived such experiences as a personal failure, one that called into question the choices they had made to move their families elsewhere. Today there is growing awareness that such an experience is part of a history of systemic racism and inequality in the arts. Giving it voice, as this article attempts to do, is a strategy for individual and collective healing and empowerment—as is giving space and visibility to artists who have been, like P.Mansaram, too long overlooked.