The personal trajectory of Zainub Verjee over the past four decades intersects with cultural moments that continue to resonate.

Born in Kenya and educated in the UK, Verjee arrived in Canada in the 1970s to study economics at Simon Fraser University. A close collaborator with Ken Lum in the early years of Vancouver’s photoconceptualism movement, and with Sara Diamond on a history of women’s labour in British Columbia, Verjee also helped build the international profile of the Western Front throughout the 1990s. Her policy work on the BC Arts Board in the early 1990s helped produce the province’s Arts Council Act, leading to the formation of the BC Arts Council, and she later worked on early digital initiatives at the Canada Council for the Arts and the Department of Canadian Heritage.

As a practicing artist in the 1980s and ’90s, Verjee was included in national and international group exhibitions, including “New Canadian Video” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1994; “TransCulture,” a satellite exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1995; “Traversing Territory, Part II: Road Movies in a Post-Colonial Landscape,” curated by Judith Mastai for the Portland Institute of Contemporary Art in 1997; and “Tracing Cultures III,” curated by Karen Henry and installed at the Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre in Burnaby in 1997. (“A first when contemporary art was shown in a mosque in Canada,” says Verjee.)

One of the defining legacies in Verjee’s career is In Visible Colours (IVC), an international festival in Vancouver dedicated to film and video by women of colour that she co-founded, with Lorraine Chan, in 1989. A landmark event of its time, IVC assembled works by then-emerging artists such as Tracey Moffatt, Gurinder Chadha, Alanis Obomsawin, Merata Mita and Mona Hatoum. IVC and the issues it foregrounded is one reason why, from Verjee’s perspective, the identity politics of today is in large part a return to a conversation that started in the 1980s.

Rosemary Heather: It’s been almost 30 years since you staged In Visible Colours, with more than 100 films and videos by artists from 28 countries and 75 international delegates in attendance. The event focused on global issues around diversity and representation. What do you think has changed in the intervening time? Have we seen any progress?

Zainub Verjee: In Visible Colours emerged amid contestations on nation building and the making of a global neoliberal order, as much as the social and political upheavals of the late 1970s and ’80s that foregrounded race, gender and the politics of cultural difference.

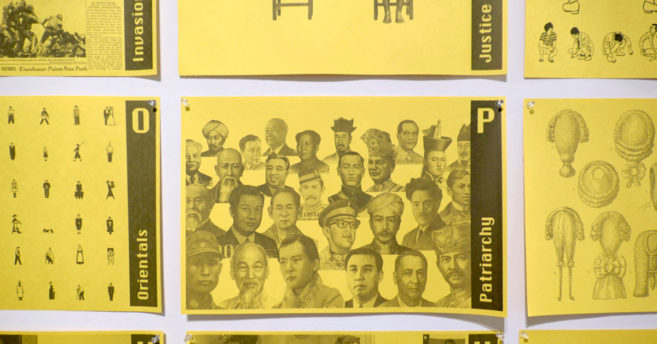

IVC was primarily about the contested history of the modernist aesthetic and modernism in the visual arts and the making of the contemporary condition—as a historical marker—for the decolonized world. It asked: Who was defining this marker?

To reduce that conversation to diversity and representation can undermine the deeper issues of contested art histories and the politics of aesthetics. The reality today is that embedding oneself into such a discourse is still a massive challenge for people of colour, particularly women.

RH: So IVC was essentially informed by that era’s worldwide push for decolonialization, but with a stronger emphasis on discourse, correct?

ZV: IVC was made, not found; it was historically produced and was historically productive. Post-war decolonization led to a global societal upheaval.

There were transatlantic responses in the art world: In New York, for example, the Museum of Modern Art’s controversial “Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern,” in 1984, can be read in context of the ascendancy of two generations of Black artists (this includes South Asians) in the UK in the early 1980s. Their contrasting relationship to modernism, and opposition to anticolonial and postcolonial politics, resulted in the making of the Black British Arts movement.

In Canada, the 1951 Massey Report frames this nation-building project, and despite its multiple flaws—primarily its Eurocentric orientation— remains well entrenched today. The failure of the 1970 Royal Commission on the Status of Women led to a flurry of counter-events with the emergence of second-wave feminism. Race also became a major element in this collective endeavour and shook the cultural institutional apparatus. IVC was a forerunner of these phenomena.

RH: You worked with cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who was a key inspiration for Black British Arts—the radical political art movement founded in the UK in 1982 and inspired by anti-racist discourse and feminist critique. How did Black British Arts influence IVC?

ZV: Black as a label in Britain encompassed a broad range of non-European ethnic minority populations. Since I was from London and hooked into that scene, I closely followed Lubaina Himid’s set of three exhibitions beginning in 1983 and culminating with “The Thin Black Line” at the Institute for Contemporary Arts in 1985. Another important one was the one-off Third Eye festival of Third World cinema held in London and Birmingham in 1983. Together they addressed Black invisibility in the art world and engaged with the sociopolitical and aesthetic issues of the time.

Over that decade, artists and thinkers such as Hall, Sonia Boyce, Hanif Kureishi, Kobena Mercer and Rasheed Araeen, and institutions like the Black Audio Film Collective, Sankofa and Third Text, were other major influences. They informed me about the agency I had as a person of colour and how I could use that position to intervene on the racialized gender issues of cultural production and institutional discourse that had been unleashed by globalization and a new neoliberal order.

RH: Was this conversation also happening in Vancouver at the time?

ZV: Indeed. For instance, from the 1970s onwards, Chilean women in the exile community established themselves in Vancouver. Their activism against the Pinochet dictatorship influenced multiple sites: Simon Fraser University, artist scenes and centres, literary circles and left movements. Pinochet was, after all, the poster boy of the neoliberal regime!

In 1987, I started working at Women in Focus Society (WIF), a feminist, arts and media centre devoted to women’s cultural production in film, video and the visual arts in Vancouver. I recall the WIF exhibition “Mujer, arte y periferia” [Women, art and periphery], in 1987, raising complex questions about the gestures of Chilean women under dictatorship as well as the “placement” of women’s art.

It was within these larger contexts that I noticed there were no works by women of colour in WIF’s distribution collection. This overwhelming absence of the voice of women of colour in the Canadian context led to the first conversations that ultimately took the form of IVC.

RH: This sense of tumult at the end of the 1980s produced other exhibitions that were equally influential to the direction of IVC. Can you talk about that?

ZV: The two-year period leading to IVC in 1989 became coterminous with other exhibitions of equal critical import.

In Paris, in response to the colonial ethnography of MoMA’s “Primitivism” exhibition, Jean-Hubert Martin curated “Magiciens de la Terre,” presenting works by more than 100 Western and non-Western artists from 50 countries. In London, Araeen’s “The Other Story” invoked multiple modernities. And in Ottawa, Gerald McMaster’s “In the Shadow of the Sun” framed Indigenous contemporary expression without any apology, offering a definitive moment in the contemporary art history of Canada.

RH: Canada has long branded itself as a successful multicultural experiment. Is there any truth to this idea? Or does a new conversation have to happen? What would the terms of that conversation be?

ZV: The managerial template of multiculturalism emerged from the political expediency of the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism in the 1960s. Today, it is philosophically defunct. Politically, however, it is still used to package “difference” as a recited truth!

This elastic sense of multiculturalism is central to the recasting of racism today. Given the increased anxieties around race, we keep seeing the fault lines every now and then, as in the recent controversy around a so-called Cultural Appropriation Prize. Primarily, this call to “reward” cultural appropriation is flippant and a distraction from deeper issues—including the term “representation.” We continue to invent or quarrel over words! Diversity is a very homogenizing term; the culture of liberal individuality conflates difference as pluralism!

Over the past few decades we have created new vocabularies that promote an assumption that this issue has been addressed. Institutional amnesia has settled in with a normalizing effect. Today, Truth and Reconciliation is an important marker, but there is a danger in misreading the growing ascendancy of the identity politics. A wrong reading of history will create conditions for it to be consumed and pigeonholed by the same liberalism with no emancipation in sight for generations to come.

This post is adapted from an article in the Fall 2017 issue of Canadian Art.

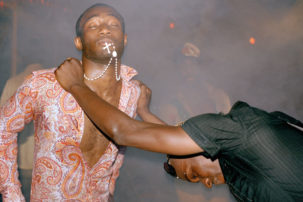

Still from Tracey Moffatt’s Nice Coloured Girls (1987), which made its Canadian premiere at InVisible Colours. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

Still from Tracey Moffatt’s Nice Coloured Girls (1987), which made its Canadian premiere at InVisible Colours. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.