I remember having a difficult conversation with a loved one at the outset of the year. Words—inscribed with power relations and never neutral—are often verbal cues that declare an apparent political dogma or stance. Alienation and miscommunication follow suit. With this conversation, I believe my loved one and I were working from the same baseline values, but our differing political and social spheres provided us with two very different sets of language, ones that seemed to sever our ability to connect on shared topics. Words became inflammatory and explosive, triggering a mutual refusal to listen. Ironically, language precluded us from communicating.

This experience and others like it had me paying special notice to the use of text and words in gallery contexts this year. As I reflect on much of the work I saw, I continue thinking about the ways language, as artistic material, can be either used or eschewed to increase the legibility of contemporary art. The three cases below use language as a point of entry rather than as a barrier—playing with language to translate complex meaning to their audiences, making their work accessible to a broader public.

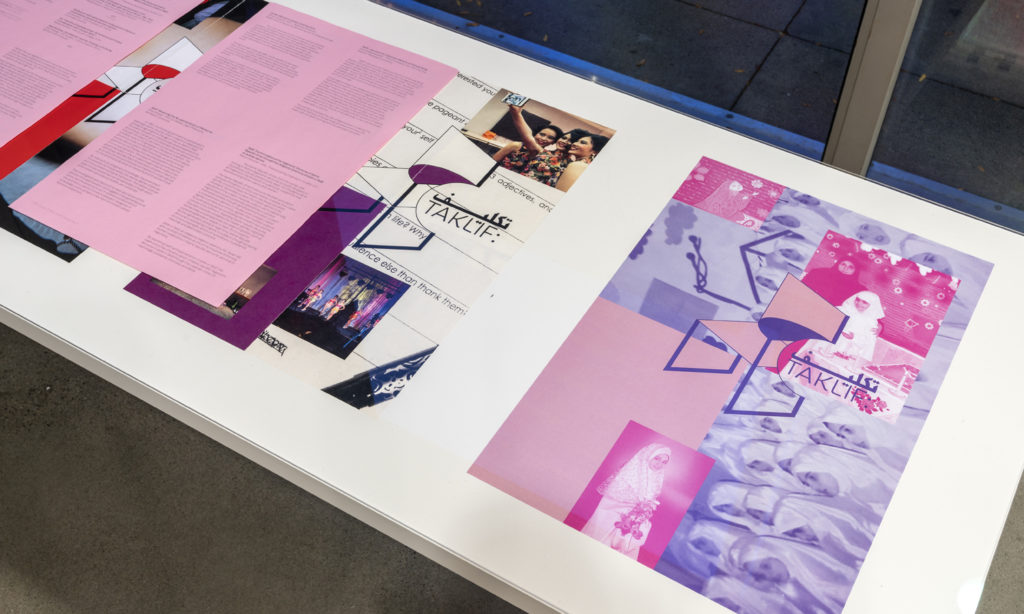

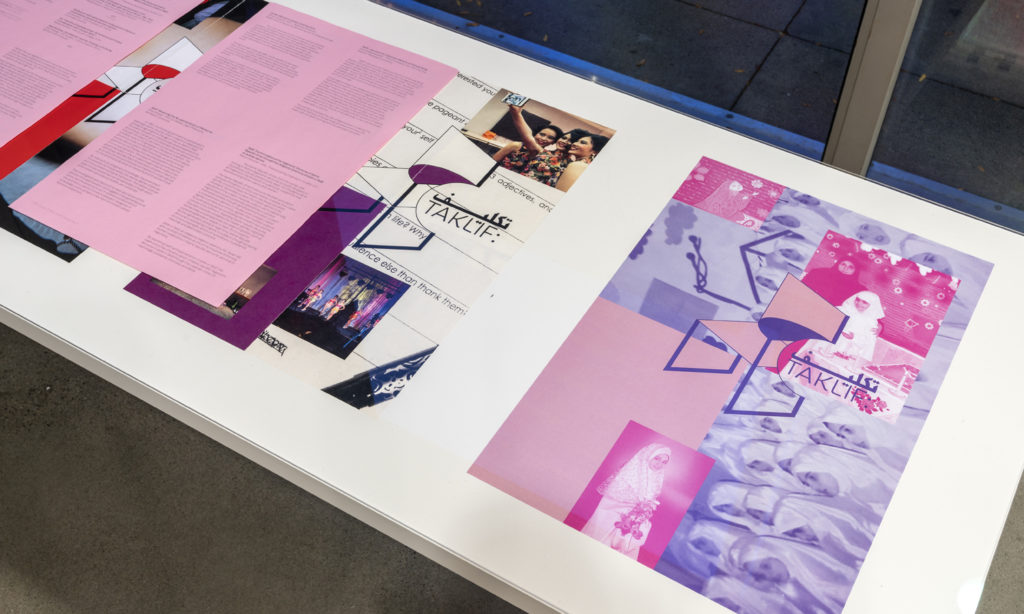

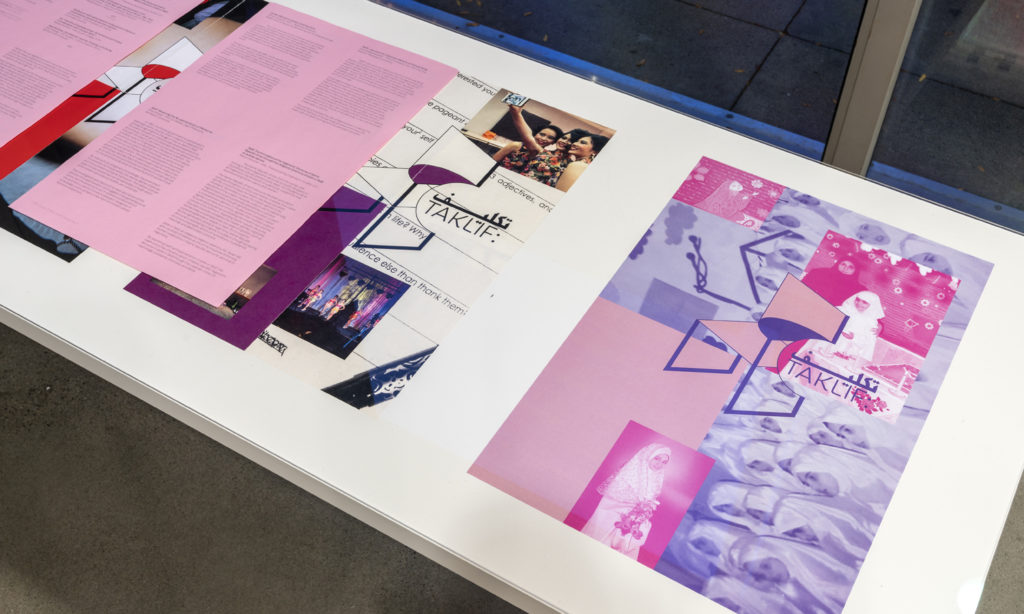

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

Taklif : تکلیف collective, Taklif: Ideas of Femininity, 2018. Image courtesy FOFA Gallery. Photo: Guy L’Heureux.

The exhibition “Taklif: Ideas of Femininity” by the Taklif : تکلیف collective, a group of young Iranian artists based mostly out of Toronto, ran for the last two months of 2018 in the main space of the FOFA gallery at Concordia University in Montreal, where I was working at the time. The artists used hanging soft-hued fabrics, personal photographs, home videos and recorded oral accounts to reflect on their personal experiences of the Jashn-e-Taklif ceremony, a religious rite of passage in the Muslim faith traditionally performed in elementary school, that marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. What I found unique about this project, especially in relation to the use of text in art spaces, was the artists’ effective mixing of two styles of language: the subjective and emotional with the formal and theoretical.

The focal point was a reading room in the centre of the gallery, fit with comfortable patterned-block seating and a curated selection of contemporary feminist and religious literature and theory. The environment was designed to encourage audience members to spend time there, and headphones placed along the seating area drew listeners in with long-form memories told by the project’s participants. The selected texts were available to pick up and read, encouraging their holders to begin forging connections between the personal stories being shared and the broader political implications of the ceremony. Though the Jashn-e-Taklif tradition continues to spur controversy for too quickly expediting a girl’s transition into womanhood (the ceremony is performed for girls at age nine, in contrast to boys at fifteen), this exhibition used personal narratives to foreground the subjective, emotional histories of the women who actually experienced the ritual, neither condoning nor condemning the practice. The work said simply: this happened; now how do we make sense of it?

Language was both an invitation and a resource. Audience members were generously welcomed into the complex territory of the artists’ experiences, encouraged first to relate, and second, to self-educate. This empathy-forward approach made accessible the often intimidating landscape of contemporary poltical, religious and feminist theory, creating an entry point through the use of memory and relational language.

In Life of a Craphead’s “Entertaining Every Second,” which opened in February 2019 at Montreal’s Centre CLARK, I found a related use of text, with the interweaving of personal histories and broader politics. Among other works, artist duo Amy Lam and Jon McCurley presented subversions of Wikipedia entries and canonical literature, mounting plaques of text on the gallery wall to highlight both the erasure and blatant misrepresentation of non-Western historical narratives. Angry Edit Of Wikipedia Page (2018) was an enlarged, printed screencap of a Wikipedia entry showing how the artists edited the “Treaty of Huế (1884),” the title notably altered to “The Totally Unfair One-sided Quote-unquote Treaty of Huế (1884) that Jon’s Great-great-great-great-grandfather Was Forced to Sign.” And mounted on an adjacent wall were four green plaques with white text and red chili pepper adornments with a poignant personal essay from Lam. In The Quiet American But Only The Parts Where the White Man Main Character Tells the Asian Woman To Do Stuff for Him (2018), Lam discusses the subservient portrayal, in Graham Greene’s 1955 novel The Quiet American, of the female Vietnamese character, Phuong, whose sole purpose seems to be to prepare tea, food, opium pipes, and her own body for the English male protagonist to consume.

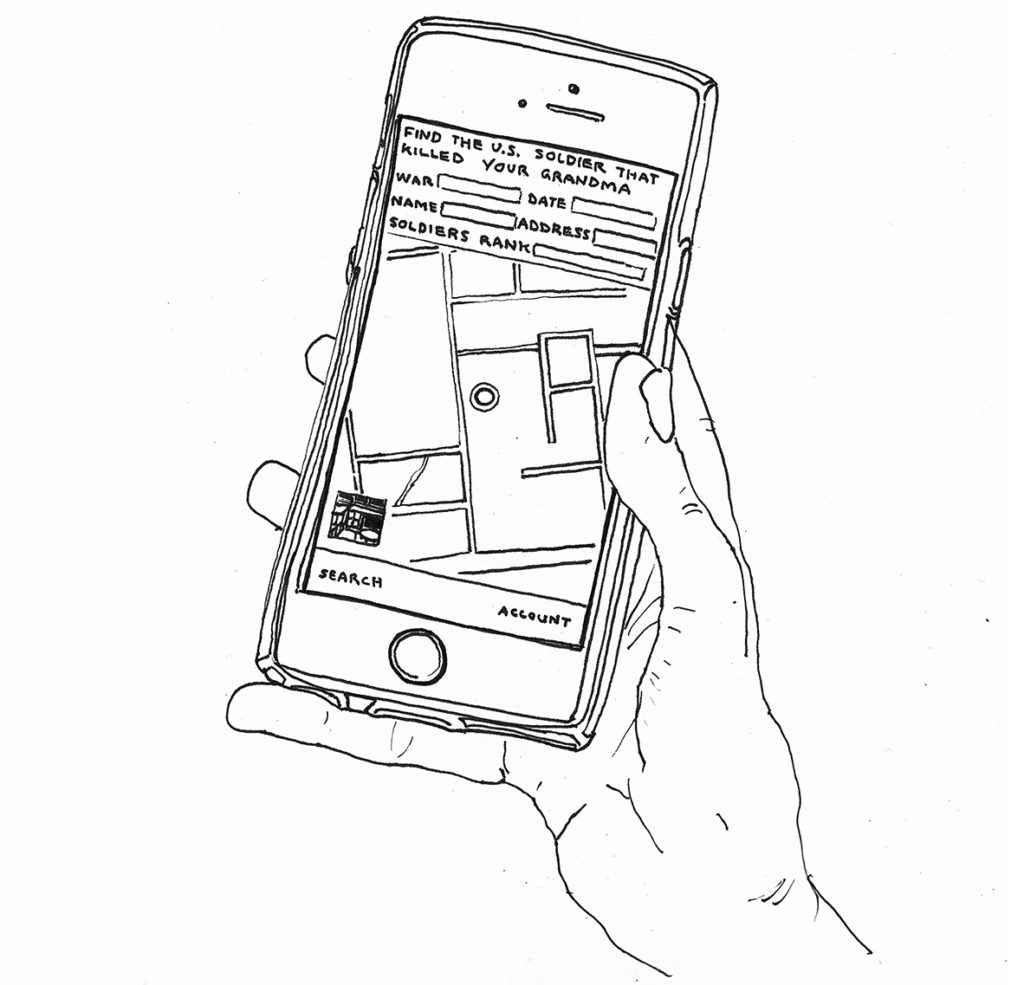

What I remember most from the show’s vernissage was seeing a quiet lineup of viewers reading the texts on the wall. Despite the three towering resin-coated foam clowns of Ceilings with Clowns (2019) overlooking viewers and the not-so-subtle use of humour in the punchline-esque titles of the individual works, the room held an air of solemnity. In particular, the raw Find the U.S. Soldier Who Killed Your Grandma (2018) became a quiet reading space for gallery-goers. Laid out across three walls, hand-drawn black-and-white illustrations with paired panels of text relayed the true story of the artists’ process of tracking down the American soldier who murdered McCurley’s grandmother during the Vietnam War. Comic-like drawings depicted the myriad webpages, documents and sites uncovered during the artists’ research process. The space between the levity of the medium and the tragedy of the content left the viewer stranded, sucker-punched, with no choice but to bear the weighty comingling of familial grief and massive historical injustice. Lam and McCurley created no barriers with their language. The illustrations and text stripped the contents of the story bare, ensuring no one missed the guts of the work due to a lack of legibility. Rather than use obfuscating language, Lam and McCurley harnessed the inviting vehicle of humour to pull the audience into the devastating depths of their practice.

Life of a Craphead, Ceilings with Clowns, 2019. Installation view, Centre CLARK, 2019. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Life of a Craphead, Angry Edit Of Wikipedia Page, 2018. Installation view, Centre CLARK, 2019. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Life of a Craphead, Angry Edit Of Wikipedia Page (detail), 2018. Courtesy of the artists.

Life of a Craphead, The Quiet American But Only The Parts Where the White Man Main Character Tells the Asian Woman To Do Stuff for Him, 2018. Installation view, Centre CLARK, 2019. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Life of a Craphead, The Quiet American But Only The Parts Where the White Man Main Character Tells the Asian Woman To Do Stuff for Him, 2018. Installation view, detail, Centre CLARK, 2019. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Life of a Craphead, Ceilings with Clowns, 2019. Installation view, Centre CLARK, 2019. Photo: Paul Litherland.

Life of a Craphead, Find the U.S. Soldier Who Killed Your Grandma, 2018. Installation view, AKA artist-run. Photo: Derek Sandbeck.

Having moved from Toronto to Montreal in 2018 and to Mexico City before that—and being fluent in neither French nor Spanish—I spent a lot of my time this year struggling for words. Body language and miming quickly became my communication tools. These experiences left me wondering about the potential power of non-linguistic communication, of relating beyond words. If we were to remove the loaded terms that make it too easy to reduce people to political categories, could we actually start talking?

Some of these thoughts germinated while watching Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau’s performance An Autobiography of Air (2019) at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in June. The work saw two performers activating a neon-bright installation, using their bodies and voices to interpret the carefully composed score. Though interspersed with operatic moments in English, the majority of the performance was bodily, guttural, working out gestural onomatopoeia through sound and movement. The performers’ delivery exported words’ texture to the body, to that airy space of aurality, stripped from written language’s linear charge forward. In this case, the audience “read” volume, dynamics, and percussion, more than words.

This sonic and physical patterning created a new form of communication that became legible beyond language barriers. Lum and Desranleau’s work illustrated the ability to manipulate the texture of language like any moldable, shapeable material, conveying meaning via nontraditional channels.

In the end, to whom is contemporary art legible, and why? Assuming that not everyone shares its languages, what new ways are there to expand art’s readership? I end the year thinking about the potential of language as an artistic medium, in both its ability to deploy incisive critique and to create moments of relatability.

This text was corrected on Friday, December 20 to more accurately reflect details in Life of a Craphead’s The Quiet American But Only The Parts Where the White Man Main Character Tells the Asian Woman To Do Stuff for Him (2018) and Ceilings with Clowns (2019).

Life of a Craphead, Find the U.S. Soldier Who Killed Your Grandma (detail), 2018. Drawing. Courtesy the artists.

Life of a Craphead, Find the U.S. Soldier Who Killed Your Grandma (detail), 2018. Drawing. Courtesy the artists.