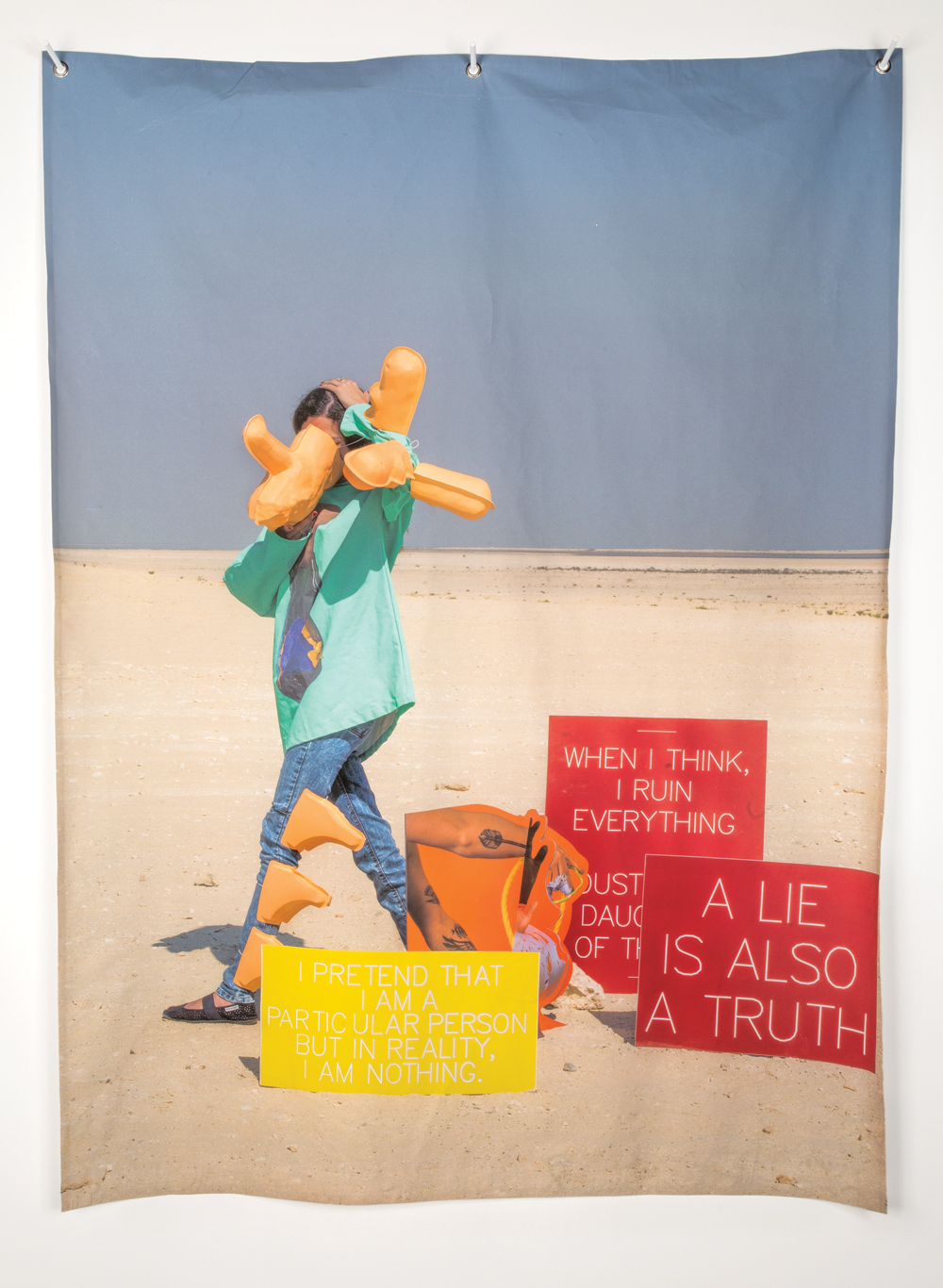

Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, I really I want Time for A Lie – A Lie, 2016. Ink-jet on canvas and grommets. 1.32 m x 1 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, I really I want Time for A Lie – A Lie, 2016. Ink-jet on canvas and grommets. 1.32 m x 1 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Since last November, life seems to have had a brittle texture, a bitter flavour. While everyday existence has continued mostly as before for me, an able-bodied, white male whose various privileges include living north of (but not in) the United States, the coordinates of the wider world have lurched nauseatingly off their rails. The unrelenting demand to think about it, to talk about him, is a psychological burden that siphons off mental and emotional energy. The news cycle has grown to a widening gyre, a black hole that swallows all attention. Writing in n+1, A.S. Hamrah called it Trumpancholia: “a psychological condition now afflicting much of the planet’s population, who have traded the things they used to enjoy for the constant monitoring of Trump’s reality-TV spectacle.” Dire consequences are visited upon many, but even for those personally, provisionally insulated from current events, living in this emotional climate is detrimental to one’s health.

Not that the anxious precarity of the Trump era is a qualitatively new phenomenon. It’s merely the latest phase of a series of shocks that extends back to (at least) the 2008 financial crisis, when the neoliberal world order first began to show serious cracks in its facade. Since then, numerous commentators—including Ann Cvetkovich, Franco “Bifo” Berardi and the late Mark Fisher—have written penetratingly on how late capitalism installs anxiety and depression as a dominant sensibility, an idea that has permeated widely into art practices. But developments that were already troubling enough—runaway climate change, ballooning inequality, political polarization, emboldened far-right movements, nativist racism, police militarization and brutality—seem to have lost any impediment to their acceleration as the illusion of liberal democracy crumbles. It feels as though the bottom has dropped out on the world; we’re all in free fall now.

And how have the power centres of the contemporary art world responded? Much like the centrist pundit class, with a combination of ramped-up denial and compensatory affirmation. Instead of a radical rethink of priorities, those with the largest platforms have been desperately fantasizing about reinstating the status quo, returning to a now-vanished state of normality that may never have been more than a mirage. Take the 57th Venice Biennale, “Viva Arte Viva,” which was billed as “a passionate outcry for art and the state of the artist,” an overwrought bid to assert art’s universal significance; likewise, Adam Szymczyk’s beleaguered Documenta 14 attempted to double down on the most established vehicles for conveying “the political” in art: conceptual gestures, archival and documentary modes, participatory and relational projects, and performative and pedagogical events. The response to these mega-events has been almost uniformly dismal, spawning a growing chorus of voices questioning the current relevance of biennials in general.

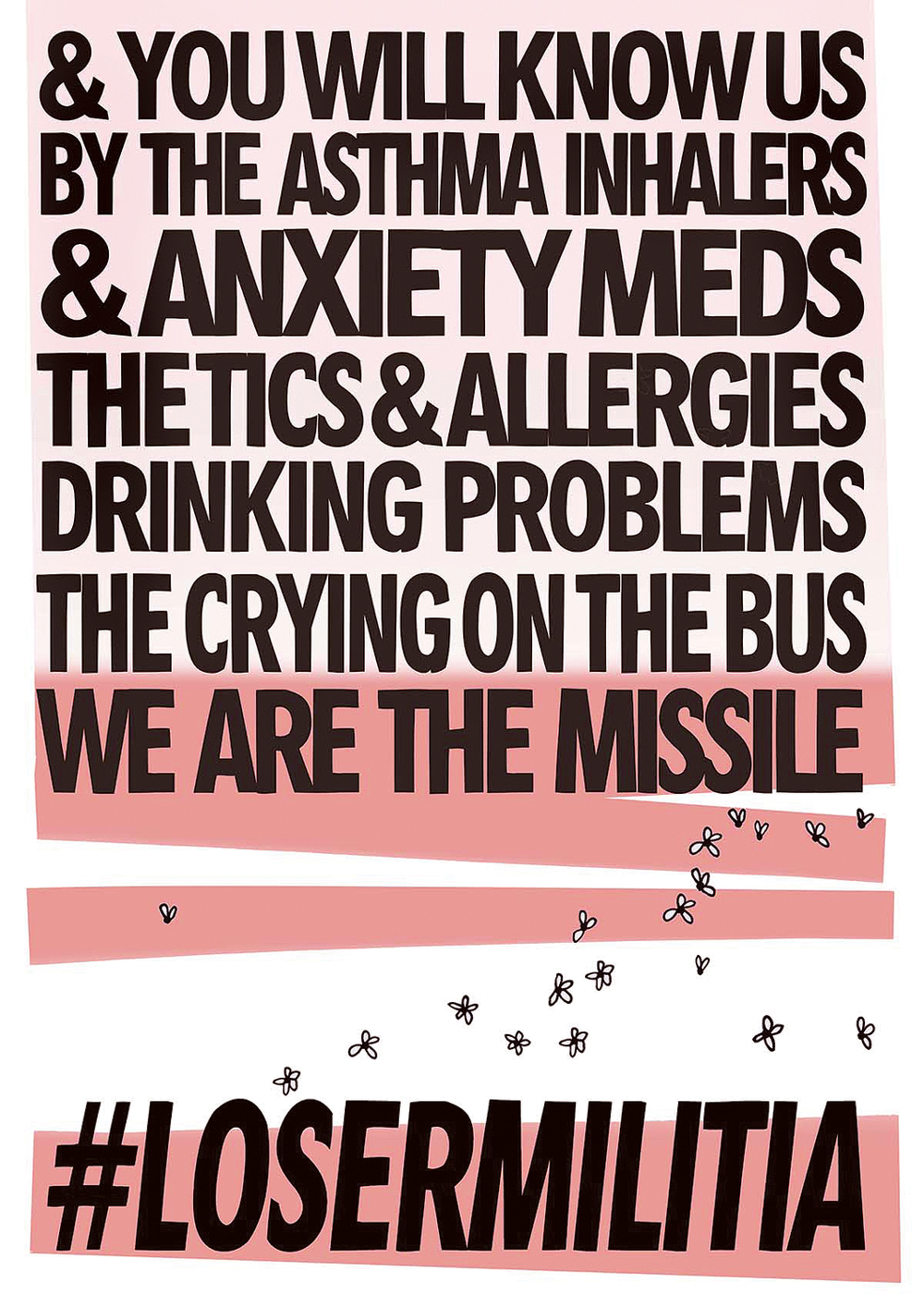

Jesse Darling, NEOLIBERAL AGITPROP PROTEST POSTER, 2013. Digital pigment print on cyclus paper. 86 x 62 cm. Courtesy Banner Repeater.

Jesse Darling, NEOLIBERAL AGITPROP PROTEST POSTER, 2013. Digital pigment print on cyclus paper. 86 x 62 cm. Courtesy Banner Repeater.

In place of false confidence, then, might it be more useful to start from a position of doubt and uncertainty? To cope with crisis by acknowledging one’s own vulnerability and lack of answers? To take the pulse of the moment, I spoke to a number of artists whose work probes the intersection of personal and political anxiety with mental and physical unwellness.

Montreal artist Tricia Middleton—who describes her work as an attempt at a “more effective emotional analysis of capitalism”—tells me about how, in the Melanie Klein school of psychoanalysis, melancholy is an indicator of healthy development, the inevitable consequence of getting past denial and recognizing the truth of a situation. And, often, things are deeply fucked in ways that we have only limited agency to affect. Melancholy is thus a product of confronting and accepting the denied situation. “Denial,” she deadpans, “is why we keep having these biennials year after year.”

Middleton emphasizes that there are positive aspects to the melancholic position, such as the ability to step back, to witness without having to adopt a reactive stance, and she advances an ethic of subtle refusal or withdrawal as a healthy response to unhealthy circumstances. Her own practice has shifted accordingly. While recent years saw her move from large-scale, immersive installations into more lightweight, sculptural assemblages, she has also been absorbed in a poetic writing project that she envisions as a kind of “handmade fashion magazine extrapolated from the spirit beyond.” It’s more intimate and materially ephemeral than anything she’s done before, a process-oriented activity whose final form remains (as yet) undetermined.

Walter Kaheró:ton Scott, whose beloved Wendy comics distill the quintessential experience of the millennial artist as a stressed out, self-medicated basket case, similarly opposes a reactive approach to political pressure: “Someone once commented on Instagram, asking me to write a Wendy comic ‘about the election!’, and I found it totally annoying,” he tells me. Insofar as recent events have impacted his work, he comments that they’ve strengthened his resolve to stick to his established schedule of publishing a Wendy book every two or three years. “The way content is consumed, and our emotional responses to it, is so quick that it seems like witnessing many small bursts of flame from our devices, leaving a constant layer of ash on our fingers,” he writes. “It leaves us with this ashy residue of being emotionally unresolved and we smear it everywhere, in our personal lives, in our rooms, on other people.”

Jaakko Pallasvuo, a Finnish artist who also makes comics (along with videos, sculptures and various other things) that satirize the art world and anatomize his own self-doubt, believes that it’s hard to identify a specific political turning point. “It’s been this gradient of things turning worse for a longer time,” he says, “an international development of countries rediscovering fascism and authoritarianism. Trump feels the scariest because the power attached to it is the biggest, but it also feels like only the fifteenth in a series of chilling events.”

If Pallasvuo has adopted something akin to Middleton’s melancholic position, it started well before the last year. He tells me about how, being involved with the early phase of post-internet art, he was immersed in the scene’s prevalent quasi-ironic optimism about capitalism (embodied by collectives like DIS and K-Hole). “I got so sick from it,” he says, “that I’ve been in crisis from that point until now. But now it’s beginning to match more with reality. Feeling that life is impossible is becoming the main vibe rather than just my problem.”

Pallasvuo’s strategies for coping echoed comments made by many of the artists I spoke to: embrace being peripheral (in terms of genre and geography), make work that circulates easily and cheaply (such as video and books), invest in collaboration, and seek out public money when you can. Pallasvuo is currently supported by a media arts grant from the Finnish government, though he hastens to add that nationalist funding systems come with their own baggage. “Public funding is often contingent on where you’re based or which passport you have,” he notes, “which is itself a very asymmetrical, uneven thing.”

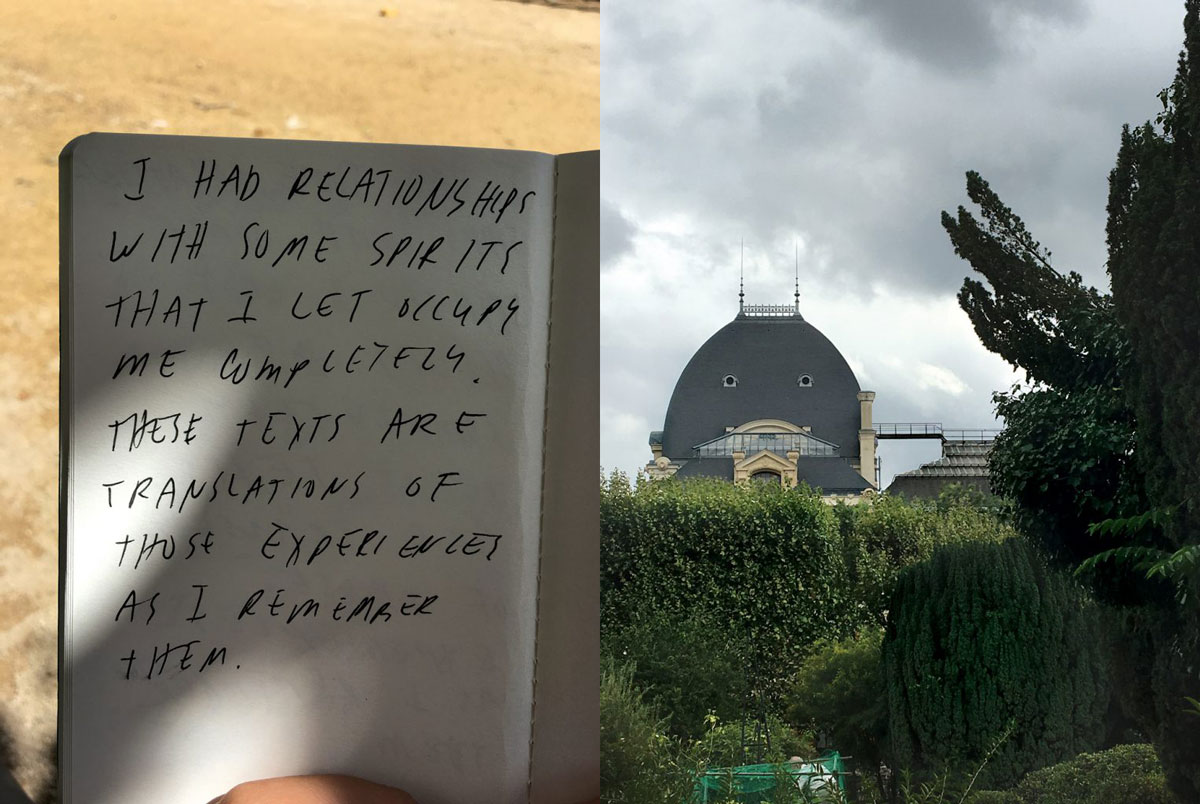

Excerpt from Tricia Middleton’s Trouble with boundaries (1785–) recorded on August 5, 2017, between 2:53 and 3:16 p.m. during a regular session with the turret adorning the Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Jardin des Plantes, Paris.

Excerpt from Tricia Middleton’s Trouble with boundaries (1785–) recorded on August 5, 2017, between 2:53 and 3:16 p.m. during a regular session with the turret adorning the Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Jardin des Plantes, Paris.

Artist and writer Jesse Darling discusses how, for them, asserting a collective failure to perform under neoliberal capitalism is of a piece with the necessity of acknowledging crisis (personal and historical) as a “foundational principle of all things, ideas, technologies, bodies and societies.” Everything is vulnerable, everything breaks down, fucks up and eventually dies. “Nothing and no one is too big to fail,” Darling insists, and acknowledging this fact is a form of “precarious optimism.” This was the basis of Darling’s #losermilitia (2013), a hashtag slogan that spawned a poster project, the idea being that a dysfunctional distributed community can act as a weapon aimed at capital’s overbearing demands.

“I do feel like the missile when feeding my baby under the green sign of Starbucks with mobility cane and all the androgynous sports gear I’m probably too old to carry off,” Darling writes to me. “The very repudiation of what liquid-modern neoliberalism demands of its labourers: to remain young, lean, legible, capable, flexible. Wearing my wounds on the outside and flanked by what slows me down. ‘We’re undone by each other,’ wrote Judith Butler, and I keep that tucked into my heart.”

Yannick Desranleau and Chloë Lum, the Montreal- and Toronto-based collaborative duo formerly known as Seripop, found that, when Lum was diagnosed with a chronic illness, the work they were already doing began to take on a more autobiographical resonance. Their recent approach has been based on choreographed interactions between performers and sculptural props and sets (whether live or for videos or photographs) that speak to bodily vulnerability and the need for support. The improvisational and collaborative nature of their work makes doubt and uncertainty into something of a virtue. As Desranleau puts it, “We want a sort of openness about how we do our work, without being preachy or didactic about it.”

Both Desranleau and Lum make it clear that they are able to support their practice thanks to the strength of the non-profit arts infrastructure in Canada. “Being both from working-class backgrounds,” Lum says, “the only way we could have the freedom and ability to work the way we do has been due to the artist-run culture of Canada, CARFAC and the granting agencies. It’s allowed a couple of dishevelled weirdos from the noise-punk scene to do large-scale, ambitious works where we can explore all our neuroses and obsessions and invite our peers to join in, laughing through tears.”

Lum reminds me that doubt is not the same as despair: “I think the most important thing, in trying to be an ethical actor as an artist, is to realize the extremely limited power of art,” she says. “However, realizing this limited scope doesn’t equal nihilism. It can mean living and working according to your ethics, doing what you can to put money in the hands of other precariously living folks, it can be dialogue and critique and celebration within one’s community, city, country and hoping to be kindly corrected when needed. Everything might suck, but we are alive and life can be full of beauty despite the toxic systems that capitalism, white supremacy and misogyny have wrought.”

Saelan Twerdy is a writer based in Montreal, a PhD candidate in art history at McGill University and a contributing editor at Momus.

This is an article from the Winter 2018 issue of Canadian Art, which is themed on “Care and Wellness.” It will be on newsstands from December 15, 2017, to March 14, 2018.

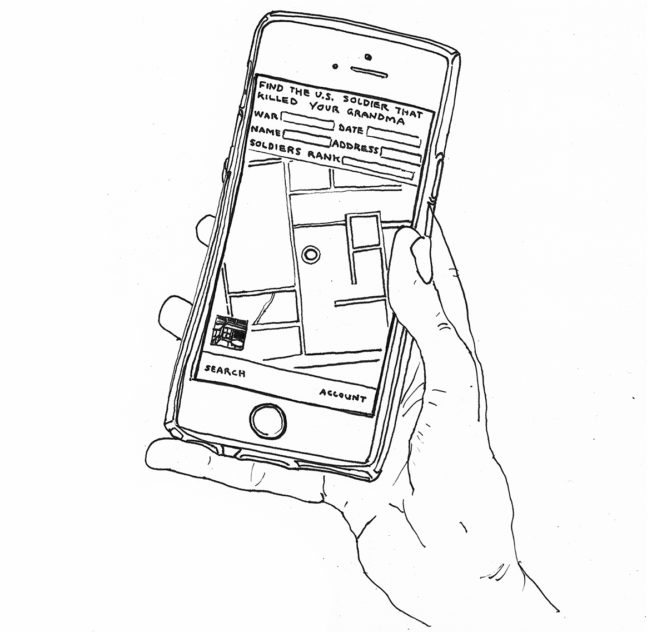

Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, I really I want Time for A Lie – A Lie (detail), 2016. Ink-jet on canvas and grommets. 1.32 m x 1 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.

Chloë Lum and Yannick Desranleau, I really I want Time for A Lie – A Lie (detail), 2016. Ink-jet on canvas and grommets. 1.32 m x 1 m. Courtesy Galerie Hugues Charbonneau.