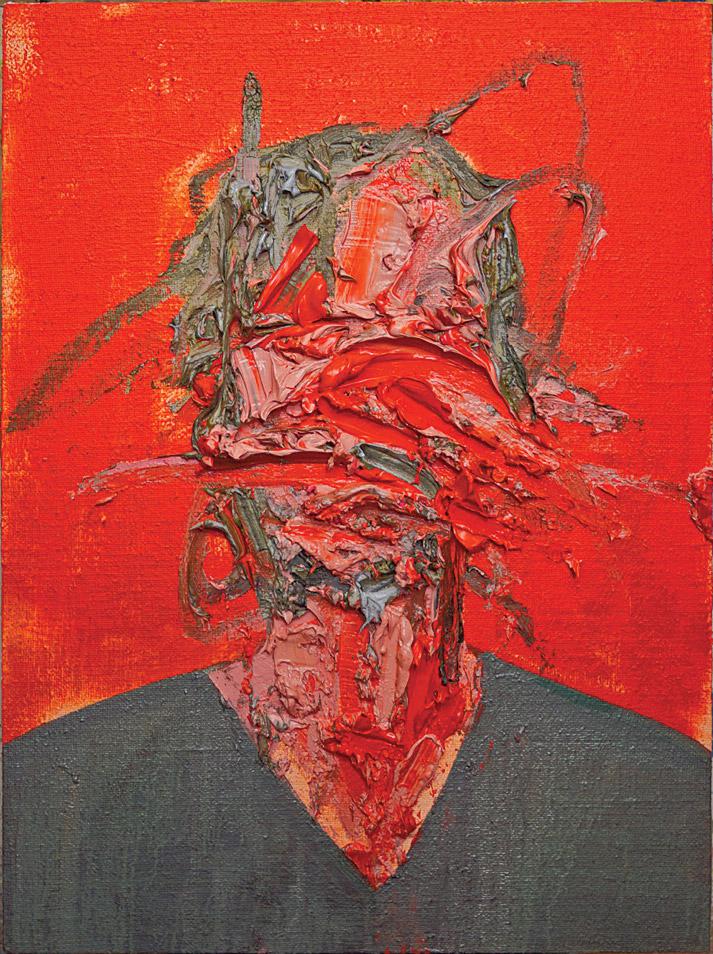

Toronto painter Kim Dorland is synonymous with big paint. At times, the surface depth of his canvases exceeds four or five inches. The paint is visceral. He works with it like coloured clay, fashioning a sculptural experience as much as a painting experience. Dorland helped put the extreme in extreme painting.

For all this expressive dimensionality, however, he is also a remarkably delicate painter. The usual experience in looking at painting is to see a surface intensify as you look. The paint acquires fluid, tactile presence, the colours gather richness and the image becomes louder, more assertive.

Dorland plays with this framework and does something new with it. He inverts the usual process by speeding it up. At first glance, his paintings are already grossly tactile, intensely coloured and splashily vivid in their imagery. Their in-your-face mode of address is a given, which is why it’s a surprising delight to see the paintings actually grow quieter, more subtle and more nuanced as you spend time looking at them. They build room for reflection inside the loudness of their presence. For all their brashness, they savour an expansive quietude that carries from the landscape where many of them are set.

Dorland’s latest show revolved around portraits, family groupings and recreational forests, most of them rendered in bright fire-red. The press release for the show talked about “warmth,” and the sun images that cut through the forests are something that Dorland gives bodily form with his paint. One of the joys of the show was to see this repeated conflation of paint and image, where Dorland uses bulked-up paint to bring a setting sun through the trees to reside in the literal foreground of a painting. It is a distant image object brought close. In contrast with the vertical compression of the forest space, it reads as an optimistic release, a change of outlook.

Dorland titled his show “I’m An Adult Now” and used it to contextualize paintings that celebrate his family in a reddened space that is not without implications of danger alongside the visions of warmth. The words are a touching recognition of responsibility spoken through paintings that show a rich intersection of paint and image, an intersection that conveys an intense and lively communion of body and mind.

The portrait Wading in (2012) stands apart from the other paintings in its flatness. With a few expert licks of red, Dorland shows himself wading out into water, alone and looking down. In the context of the other pictures, it makes you want him to turn around and come back in.

This is a review from the Winter 2013 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.