In December, the Vancouver Art Gallery launched “Vancouver Special: Ambivalent Pleasures,” the first iteration of a triennial showcase of contemporary Vancouver art. The project aims to map art in the city via works produced during the last five years, an epoch the curators Daina Augaitis and Jesse McKee refer to as “post-Olympic.”

While the term “post-Olympic” asserts relevancy to the current moment, this exhibition poses several problems that in fact come from larger histories and narratives. Firstly, the exhibition uses opaque and loaded terminology. It understates the toll that Vancouver’s expensive housing market places on artists, with the insinuation being that such inaccessibility is productive for hedonistic escapism. Secondly, the curatorial selection plays into age-old dichotomies tethered to Vancouver’s art discourses. Lastly, a compliance with the problematic standards embodied in the institutional model of the “survey” show limits the exhibition’s scope and impact.

Whose Special? And Why?

The Vancouver Special is a housing model that was popular between the 1960s and 1980s for being, as the exhibition wall text states, an “affordable and easily adaptable” option for homeowners. The exhibition situates this housing model as a relic—one that has received “renewed attention in the midst of the current housing crisis.” But what this attention entails is unclear. We don’t know whether the exhibition text is referring to the renewed value of such architecture in the housing market, or if this means renewed artistic attention, as in Ken Lum’s miniaturized replica Vancouver Especially (A Vancouver Special scaled to its property value in 1973, then increased by 8 fold) (2015).

The Vancouver Special is indexed by this exhibition mainly as a measure for Vancouver’s decline as an affordable city. What isn’t mentioned is that the Vancouver Special was particularly popular among immigrants in suburban areas, and that a large part of its allure was its remunerative capacity to house several families or tenants in one structure. Rather than using the Vancouver Special as a foil to highlight the relative accessibility of homeownership in the past, it would be more useful to situate this relic as an important reminder of Vancouver’s history of contested spaces, diaspora and investment.

Derya Akay, cyclodrum, potbound & soup from stone, 2015. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of the Gardiner Museum.

Derya Akay, cyclodrum, potbound & soup from stone, 2015. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of the Gardiner Museum.

Romance, Real-Estate and the Road

The title of this first triennial exhibition, “Ambivalent Pleasures,” cites the resilience of Vancouver artists by championing their “capacity for pleasure in a variety of ways.” It suggests that despite the “contradictory conditions” of contemporary life, “widening divisions of wealth, technological acceleration and global warming,” artists in Vancouver maintain a joie de vivre, and that they do so through their materials. As viewers, we are encouraged to see the art in similarly pacifying ways, as “encountering these artworks reminds us to be conscious of finding our own modest pleasures.”

This idea of pleasure glosses over the ferocity of the issues that artists and others currently face, and romanticizes the creative outcomes that stem from their onerous effects.

For this exhibition, the term “local artists” includes “long-term residents” and “newcomers” as well as artists that are “nomadic, less settled in one place and…working energetically between several locations.”

The metaphor of the nomad was popular in postmodern social and cultural theory during the 1990s and is rearing its head again, now, in the current discourse on Vancouver’s art economies. The nomad metaphor connotes someone whose home is movement itself. Nomadism therefore cannot be defined as characteristic of a specific place because it operates foremost on the critique and evasion of organized space.

The nomad metaphor can be dangerous, because it generalizes an experience of movement. It becomes a blanket term for fragmented or shifting subjectivities. Nomadism, for instance, refers to a mobility different to the real extremity of displacement or exile faced by migrants, refugees or disenfranchised Indigenous peoples. The complexities and differences in our experiences of movement become smoothed over. Art historian Janet Wolff pointed this out when she claimed that to suggest that mobility is free is a deception, “since we don’t all have the same access to the road.”

This is not to negate the observation that the economic constraints of Vancouver have become creatively resonant in the work of many artists. One example included in the exhibition is Derya Akay’s cyclodrum, courage, bread, and roses, culture and tomatoes (2015–16), a site-specific installation of found, borrowed and immaterial elements, as the title suggests, taken from the gallery and displayed in a mesmerizing, mobile-like structure. This work, as with much of Akay’s practice, offers a poetic microcosm of, as the wall text describes, the “rhythm and fruits” of cultural production. It engages with the debris of a specific site in an economical and repurposed way, and yet, as a finished structure, it becomes abundant rather than frugal. Akay’s is an innovative intervention that engages not only with spatial structures, but also with our human traces of volume, mass and material.

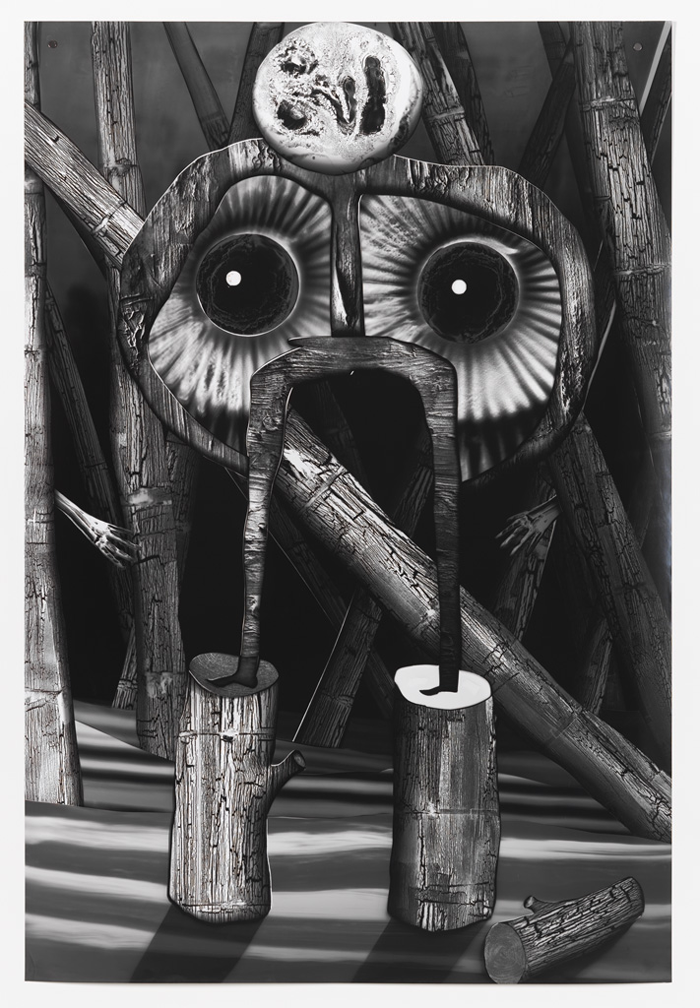

Ryan Peter, Autogram (Double 2), 2016. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Ryan Peter, Autogram (Double 2), 2016. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Painting vs. Photography: A False Dichotomy

With emphasis on how materiality can counteract contemporary crisis, “Vancouver Special: Ambivalent Pleasures” is an exhibition dominated by the idioms specific to painting. The notable absence of photographic work on display situates the show within a dichotomy between painting and photography that has recurred in the discourse of Vancouver art for many decades.

Several small-scale photographs feature sporadically throughout the exhibition, as in works by Arvo Leo and Glenn Lewis, but, in both cases, the photograph is a corollary to an accompanying (and often object-based) artwork.

The main photographic work on display is a series of autograms by Ryan Peter. Peter’s practice merges darkroom processes with textural experiments, often derived from acrylic paint. In 2009, he was a semi-finalist in the RBC Canadian Painting Competition. His works in “Vancouver Special,” like his large-scale unique gelatin silver print Autogram (Double 2) (2016), offer figurative scenes that allude to the mark-making of brushstrokes. This is a dressing of photography as painting.

It’s possible that the lack of photography in “Vancouver Special” was a strategy to move beyond the branding of art in Vancouver as predominantly photographic, a status quo that has been instated by the now-mythic historicization of the photoconceptualists.

In this omission, however, the exhibition effectively overlooks the relevance of photography for a different generation. It excludes artists who see their photo-based practice as separate from both the conceptual legacies of earlier Vancouver photography, as well as the Modernist painterly histories of the region.

Certain artists in “Vancouver Special” do engage directly with Modernist painterly histories, as in the charismatic works of Alison Yip, Angela Teng, Tiziana La Melia, Tristan Unrau and Kim Dorland.

In other instances, though, the painterly framework of the exhibition curtails the potential to unpack the divergent materials and practices on display. The works exhibited by Barry Doupé, for instance, stand out in their technical rendering and formal quality, and could be construed as painterly. Doupé creates hand-drawn, computer-generated animated films using 1980s software inbuilt to the Commodore Amiga model personal computer.

Doupé is certainly “painting” with digital technologies, rendering strokes of what we now read as outmoded graphics in low resolution. Examining his digital drawing Inward Face (2016) under the influence of surrounding paintings conjures a formal comparison to earlier 19th-century paintings, like James Ensor’s The Intrigue of 1890.

The problem here is that Doupé’s work, under the exhibition’s frame, becomes bound to a painterly history rather than prompting consideration of the independent structures unique to computer-based art.

One solution could have been to place Doupé in conversation with other computer-based digital work being made in the city, such as that of Nicolas Sassoon. Here, it is also surprising that the work of Elizabeth Vander Zaag is omitted. Vander Zaag, who has featured computer technology in her art practice since 1976, was a pioneer of the medium in Vancouver.

Jeneen Frei Njootli, Through the Body. Where is the work? g’ashondai’kwa (I don’t know), 2016. Photo: Michael R. Barrick, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

Jeneen Frei Njootli, Through the Body. Where is the work? g’ashondai’kwa (I don’t know), 2016. Photo: Michael R. Barrick, Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

The Survey: Restrictions of Rationalized and Territorialized Space

The implicit tensions of accurately representing place in “Vancouver Special,” as well as the oversight of various important streams of art being made in the city, raise a larger question about the efficacy of survey exhibitions in our current global context. According to the exhibition text, local survey shows began with the Vancouver Art Gallery’s “BC Annual Artists Exhibition,” which ran from 1932 to 1968. These exhibitions were credited with “sustaining engagement with the contemporary artists who make Vancouver a dynamic art community.”

To be sure, survey shows reinforce and encourage the local art ecology by providing artists with the attention usually given to international players. Survey shows can also place a wide variety of artworks in proximity that might otherwise have remained isolated. In “Vancouver Special,” this is done successfully in the juxtaposition of emerging artists like Jeneen Frei Njootli, Matt Browning and Krista Belle Stewart with established artists like Lyse Lemieux, Elizabeth McIntosh and Gareth James.

But the survey exhibition as a model is problematic in its reliance on rationalized and territorialized space. The structure of the survey is similar to that of a world’s fair, but internalized. Rather than offering a microcosm of macro-cultures, the survey lends micro-culture validity by placing the artworks in an institutional space that is legitimized as a gateway to the art world at large. This inversion can be disorienting to encounter. Art that might have been familiar on a community level becomes severed from the local art ecology when it is asserted as being representative of place.

The survey exhibition also operates on arbitrary distinctions between centre and periphery, because it consistently prioritizes attention on the urban over the rural. This urban focus is often at the detriment of gaining a wider perception of place-based art trends, which could be enriched by the inclusion of artists practicing in Indigenous territories and across the remote regions of the province. We need to actively re-conceptualize the framework of survey exhibitions at a local level. Larger institutions like the Vancouver Art Gallery could do so by engaging in more frequent small-scale exhibitions that create a midpoint between outlier and centre. Perhaps this begins with a reconsideration of how we define “local” art.

April Thompson is a writer and curator currently based in Vancouver. Her practice is guided by critical investigation of contemporary art, postmodern geography and spatial politics.

Kim Dorland, Egress, 2016. Courtesy Equinox Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art

Gallery.

Kim Dorland, Egress, 2016. Courtesy Equinox Gallery. Photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art

Gallery.