It begins in media res: an empty tarmac, a plane descending. The footage is from March 1990, and it shows Bulgarian refugees defecting at Gander International Airport.

This newsreel, more than a couple of decades old, is part of “The Free World,” an exhibition at the Rooms curated by Mireille Eagan.

Some 3,000 Bulgarians defected in Gander during the 1990s. Of that number, only 30 or so stayed in Newfoundland. Some of these migrants became artists, or continued their art practices here. “The Free World” tells something of their story.

Part of the emotional punch of this exhibition—and it is deeply affecting—can be attributed to Eagan’s masterful curatorial skills. She employs a complex layering of information and imagery to situate these artists’ work in an historical context. Eagan’s curating deftly tells a dense and textured narrative: Why these artists came, and why they stayed.

And part of the emotional punch of this exhibition might be attributed to the resonance it strikes with the current global refugee crisis, and the influx of more than 25,000 Syrian and Iraqi refugees finding new homes and lives in Canada today—not to mention our growing awareness that there will likely be more such migrant crises yet to come.

The installation for “The Free World” at the Rooms includes black and white photographs of each of the artists, who first arrived in Newfoundland as Bulgarian refugees in the 1990s.

All newsreels from the past have a fetishizing patina, the gilt of nostalgia. There is the glamour of being rescued from what we used to call “the cutting room floor.” We know, by virtue of its existence, that the clip has significance. We subconsciously register the slightly outdated visual tropes: the too long, formally centred, unbeautiful but sombre shots.

The calibrated momentum in this clip is strangely accelerated by the near lack of content. Time balloons during the 15 minutes, and yet the viewer remains glued to the screen. We already know what will happen; we have lived through the end of the Cold War (or been born after it, in some cases). And yet the unfolding is the essence.

It is necessary to watch.

Along with the video, the walls of this small room off of the main space of the “Free World” exhibition show black and white photographs that illustrate the history of the Gander International Airport.

We are reminded, for example, of the planes that were grounded in Gander during 9/11. This airport was once the biggest airport in the world, handling roughly 13,000 aircraft a year. It was of strategic importance, during the Second World War, as a refuelling station for trans-Atlantic aircraft. And in some cases, it was a place where lives were changed forever.

A view of the Gander Air Terminal circa 1960. Once the largest airport in the world, Gander is where some 3,000 Bulgarian refugees defected in the 1990s. Photo courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division, B 8-193. Provincial Archives photograph collection. Photo: Bill Croke [196-].

Along one wall of the main gallery, there are the enlarged passport photographs of the five Bulgarian artists whose work forms this retrospective—Vessela Brakalova, Luben Boykov, Elena Popova, Veselina Tomova and Ellie Yonova—coupled with personal statements about their art-making and immigration experiences.

Another component of this exhibition, designed by curator Jason Sellars, is an interactive space where gallery-goers are invited to affix a piece of coloured yarn to a giant wall-mounted wheel. Viewers respond to a question—“What makes you move?”—by attaching both ends of the twine to studs on the rim of the wheel, each stud labelled with possible reasons for moving. Some of the reasons included on the wheel: eviction, climate, education and adventure.

(On my fourth visit to this exhibition, I watched a mother and her preteen daughter affix separate pieces of twine to this wheel, expressing very different reasons for moving, though I assume they moved together.)

The resulting cat’s cradle of criss-crossing coloured lines on the wheel evokes an abstract expressionist map of desire and migration.

In another interactive artwork, gallery-goers are asked to stick a coloured dot to a map of the world on the place they call home. Not surprisingly, Newfoundland has been completely covered in layers of coloured dots.

In one of the interactive activities in “The Free World,” visitors are asked to place a coloured dot on a map at the place they call home.

Of course, at the emotional and aesthetic centre of “The Free World,” beyond the archival material and interactive exercises, is the art of five of those Bulgarian migrants who chose to stay in Newfoundland after defecting in Gander in the 1990s.

Does this work reflect the hybrid of Eastern European/Newfoundland influences? Does it capture the experience of immigration? Two and a half decades later, what does that moment of arrival mean?

Historically, early local art practices in Newfoundland at this time were grounded is representation, particularly landscape and portraiture. Gerry Squires, Christopher Pratt, Mary Pratt, Helen Shepherd, Reginald Shepherd, Frank LaPointe and David Blackwood were all working in the vein of realism, stylized hyper-realism or naturalism. Often, this early work seemed driven by a desire to record the natural world, the everyday life and history of Newfoundland.

The Bulgarian artists who arrived in the 1990s brought a formal fascination with mark-marking, texture and colour, putting the materiality of the work in the foreground. But in each artist’s work, we see an obsession with the Newfoundland landscape that appears in most of the early local work here.

“The Bulgarian artists who arrived in the 1990s brought a formal fascination with mark marking, texture and colour,” Lisa Moore writes. Elena Popova’s Still Vortices (2010) is a mixed media on paper work indicative of this approach. Image courtesy the Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Collection.

Ellie Yonova is a filmmaker who arrived in Newfoundland after the first wave of Bulgarian refugees. She came to make a documentary about their experiences. The photographs she contributes to this exhibition play with the tension between abstract expressionism and the supposed objectivity of photography.

Yonova’s large-format photographs are close-ups of glass, reflected and refracted light, shadow, water, submerged flowers, leaves and stalks. There are the air bubbles that form in water and cling to the sides of a glass vessel. She captures the distortion caused by curves in the glass, or photographing through water. These are photographs of otherworldly, foreign environments. In this way, it could be argued, they do capture something of the experience of immigration.

The movement of line in these images, as well as the vivid colour, is also very like the drawings of Elena Popova, whose work is almost wholly abstract with very oblique references to the landscape.

Popova’s drawings capture a high-voltage energy in the mark-making. The fierce lines suggest the immediacy and spontaneity of dance. The marks in Still Vortices are layered dark and light together, greys and blacks with vivid reds and oranges, and might be read as long grasses, bending in a big wind.

Popova, in the statement below her passport photograph, mentions the Newfoundland wind. For months after her arrival, she waited for the wind to stop. She soon came to accept the notion that it never would, and made peace with it.

The shape of a vortex found in Popova’s drawing is also central to a drawing by her husband, Luben Boykov, called Universe Suite #3. This drawing, composed of two sections, is made of pigment on paper. Boykov arranged armfuls of long grass on white paper and spray-painted the grass and underlying paper black. When he removed the grass, the white paper beneath showed a luminous spiral. The drawing has the shape and energy of a tornado, or a constellation. The misting paint gives each trace of grass a soft halo, and the shape produces the contained energy of a coiled spring.

Vessela Brakalova’s mosaics of found glass and ceramic tile are intricate, vibrantly coloured works that illustrate the ocean, particularly the hurling power of waves and opalescent foam. Glinting mirror, stained glass, mica-sparkling and glazed tiles—some of which were collected from the floor of Paris subway stations—form the action of the tides and windswept gold and orange grasses. While the mosaic tile work seems distinctly European, the stylized landscapes here appear to be the shorelines of Newfoundland.

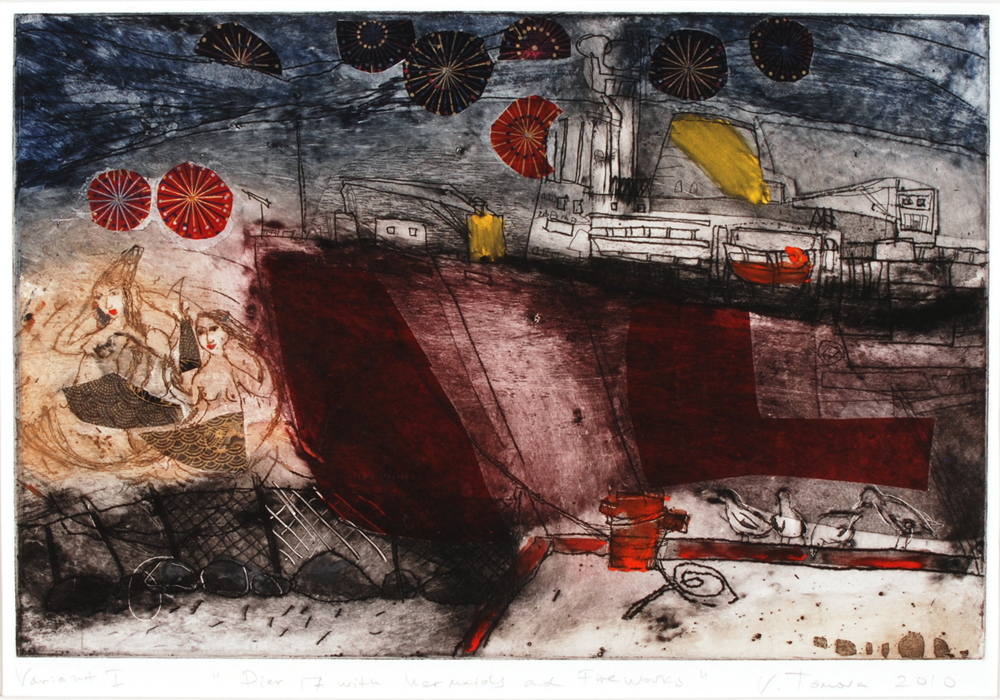

Veselina Tomova’s etchings and earthenware teapots are delicate and whimsical. Chagall-like interiors of old-fashioned outport houses, knitted socks hanging on an indoor clothesline above an oil stove, whistling kettles and free-floating brides in collaged dresses, ships riding riotous waves, angels with horns, mythical beasts and domestic animals abound. These are the playful and folklore-inspired subject matter of Tomova’s printmaking and pottery. In the etching entitled Navigating the Narrows we see an ocean-going vessel approaching the city of St. John’s through the sheltering harbour. The vessel floats through the Narrows, from the vast and infinite sea.

“The playful and folklore-inspired subject matter of Tomova’s printmaking and pottery” is a notable part of “The Free World,” Lisa Moore writes. Here is Tomova’s Pier 17 with Mermaids and Fireworks (2010), an etching, chine collé, and monotype on paper. Courtesy the artist.

But let me return to the newsreel video: a plane touches down. The air melts before the churning propellers, blurs and thickens like Vaseline. The earth is streaked with snowdrifts, stripes of tawny grass; the runway sheds veils of fog. The plane rolls to a stop. But the wide, still shot continues. It is a distancing view. It is patient.

We see that the plane is an Aeroflot plane; the lettering on the side of the plane, to my Western eye, looks like English, but something is askew. I have read that people who experience lucid dreaming can test if they are actually awake by trying to read a piece of script, a street sign, a page of typed instruction. If the writing cannot be deciphered, you know you dreaming.

For me, the viewer of this video footage, positioned beyond the tarmac, seated on the gallery bench, two and a half decades later, watching the whirring propellers make the air glassy so that everything wavers, these airplane letters are dream letters.

Nothing happens. I am transfixed. I wait. And then the door of the plane swings open.

Later, we will hear, there were fist fights. We will hear some of the passengers punched their way out. Some with their children in their arms. They only knew for certain they could defect when they saw snow on the ground and knew they were not in Cuba. There is an RCMP car waiting to escort them to safety. They stand at the open door of the aircraft, dazed by sunlight and the import of their decision. Then, they cross the threshold. They cross the runway. They face the Newfoundland wind.

This is a moment of arrival.

Giller-nominated author Lisa Moore, based in St. John’s, studied art at the College of the North Atlantic and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Her most recent novel, Flannery, was released in May.