Thaddeus Holownia photographed some 200 creatures killed by human error for his 17-foot-high print Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia photographed some 200 creatures killed by human error for his 17-foot-high print Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016). Image: Courtesy the artist.

Drawn to a deadly light on a foggy night, songbirds begin to fall from the sky. By evening’s end, more than 7,500 are rendered flightless, lifeless. Twenty-six species of songbird felled by one flame, a flare from the natural gas burn-off at the Canaport Liquefied Natural Gas terminal in Saint John, New Brunswick.

The Canaport bird kill provides the backdrop for one of the many lingering images that comprise “The Nature of Nature: The Photographs of Thaddeus Holownia, 1976–2016,” a career retrospective running at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia until May 28th.

Holownia represents the disastrous events of Friday, September 13th, 2013, on a 17-foot-high scroll hanging on a mustard wall. The newest work in the exhibition, Icarus, Falling of Birds (2016) contains approximately eight staggering, staggered columns of birds cascading headlong. Some are charred beyond recognition. Others seem perfectly preserved, like the children of Llullaillaco.

“I’m sitting and listening to the radio one morning and they announce that there’s been this tragic bird kill in Saint John,” Holownia says. “The next thing I hear is that [my partner] Gay gets a call to go out to Atlantic Wildlife because there’s a bunch of bagged birds that have been brought over there and they have to identify them.”

Holownia immediately phoned Don McAlpine, the head of zoology at the New Brunswick Museum, where the birds were eventually transported, and asked if he could photograph them. He would have to wait two more years to do so, as their bodies were entered into evidence as part of the Crown’s case against Irving and Repsol, which co-own the offending facility.

Accompanied by his friend and poetic collaborator, Harry Thurston, Holownia was finally able to take more than 200 photographs of the dead birds in the fall of 2015.

“It’s nasty as hell,” Holownia recounts. “You’ve birds that are crisp. You can’t even identify them. Then you’ve got birds that look like they just went to sleep.”

Holownia created the work with the AGNS gallery space in mind. He laid out the digital photographs in Photoshop and then printed them as a continuous image on photo paper.

Thurston gave the title its Icarus. The allusion adds a critical irony to the work. For while Icarus’ fall from the sky is synonymous with the folly of human ambition, the birds are obviously not to blame. Rather, to blame is the fossil capitalism of companies like Irving and Repsol that structures daily life in Canada and other OECD countries—a fossil capitalism that is as profitable as it is socially destructive.

Thaddeus Holownia, Whale, PEI, 2011. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia, Whale, PEI, 2011. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

The photographs included in “The Nature of Nature” “stand as a history of the play between human intervention and the landscape,” according to Holownia. They also appear to meditate on the interplay between the spectacular violence and the slow violence that defines the nature of this intervention.

Representations of spectacular violence, such as Icarus, Falling of Birds, seem especially difficult given their immediacy and immensity. Yet as viewers, we might be accustomed to orienting our discomfort with human interventions to the spectacle of a bird kill or an oil spill.

The exhibition allows for a few of these discomforting moments of spectacular violence, such as when we encounter Whale, PEI (2011). In the foreground, the beached whale’s tail hangs off the back of the truck bed as the vehicle angles out of the top right of the frame with its scarred, defeated cargo.

But overall, Holownia’s photographs powerfully capture a more elusive and formidable process: slow violence.

“Slow violence” is a term popularized by Rob Nixon to describe environmental phenomena like climate change. “By slow violence I mean a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight,” Nixon writes in his 2011 book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, “a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”

Spectacular violence is the birds being pulled into the Canaport gas flare; slow violence is the comparatively subtle, cumulative impact from the ongoing operation of Canaport.

Nixon theorizes that “[a] major challenge [posed by slow violence] is representational: how to devise arresting stories, images, and symbols adequate to the pervasive but elusive violence of delayed effects.”

What is arguably most impressive about Holownia’s work is the nuance and depth on display as he confronts this representational challenge.

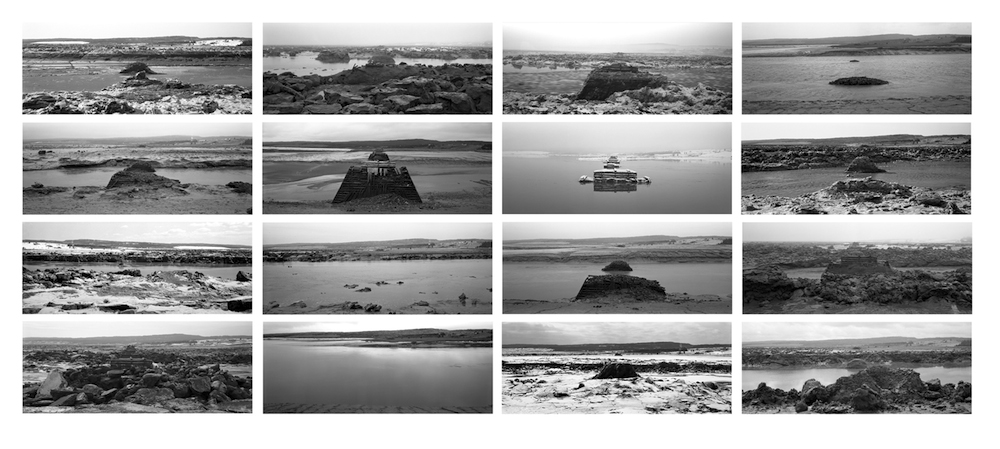

Thaddeus Holownia took photographs of New Brunswick’s Rockland Bridge for more than two decades. An array of the bridge prints from 1981 to 2000 are on view in “The Nature of Nature.” Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia took photographs of New Brunswick’s Rockland Bridge for more than two decades. An array of the bridge prints from 1981 to 2000 are on view in “The Nature of Nature.” Image: Courtesy the artist.

One of the key organizing principles of “The Nature of Nature” is that the work follows the arc of Holownia’s career as a fine arts professor at Mount Allison University, from 1977 to the present day.

He has had several major solo exhibitions over the past four decades, notably a mid-career retrospective at the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in 1997, a 25-year survey of his photographs of Newfoundland and Labrador at the Rooms in 2006, and a collection of photographs of Upper Dorchester’s Rockland Bridge at the Corkin Gallery in 1995.

Holownia was the only Canadian artist included in “Monet’s Legacy: Series—Order and Obsession,” a 2001 show at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, Germany, that also featured work by Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, and others. The show’s curator became fascinated with Holownia’s work when he saw a set of his photographs of Jolicure Pond at Art Basel. Like Monet in Giverny, Holownia would return to sites near his home, like Jolicure Pond and Rockland Bridge, in order to represent the rhythms that shape our sense of place, whether seasonal, diurnal or nocturnal.

The 20 prints of Rockland Bridge in this exhibition are the most he’s ever included in one show.

“It’s not about the seriality of the demise of a bridge,” Holownia says. “It’s about looking at nature in its progression of light and time—its permanence and change.”

Thaddeus Holownia’s Jolicure Pond, Jolicure, NB (1996) is one of several images he made at this site over the course of eight years—another kind of “extended portrait.” Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia’s Jolicure Pond, Jolicure, NB (1996) is one of several images he made at this site over the course of eight years—another kind of “extended portrait.” Image: Courtesy the artist.

Scientific understanding of “the nature of nature” has dramatically changed during the show’s four-decade timeframe. It is now widely accepted that human beings have become the primary force catastrophically impacting the Earth System—an impact so massive that it has ushered in a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. The crisis of ozone depletion, overlapping with the beginning of Holownia’s career, is commonly cited as the beginnings of popular awareness of the Anthropocene.

As scientists were discovering the effects of CFCs on the ozone layer in the 1970s, Holownia was learning to master the medium that would one day allow him to thoroughly document the effects of human intervention. Holownia uses a view camera to produce his photographic signature, the 7-by-17 black-and-white landscape. He came to the large-format device through a conversation he had with designer Allan Fleming in the mid-1970s. At the time, Fleming was the chief designer at the University of Toronto Press—and he was the first person to whom Holownia, a recent graduate of the University of Windsor’s fine arts program, had shown a substantive portfolio.

“I went to see Allan and he was very cordial,” Holownia recalls. “He told me, ‘You know, Thaddeus, looking at this subject matter I think you might consider using a view camera.’ I said, “Ok. Sounds good.’ I left there and thought, ‘What the hell is a view camera?’”

Holownia became a quick study. He purchased the Folmer & Schwing camera, on display in the exhibition, which he would go on to use for the next two decades. The first paper negative he developed on it was in the basement washtub of a house where he had just taken a fifteen second exposure.

“When it came up, it was this beautiful 8-by-20-inch piece of paper with a negative image on it, which you took and put down on another piece of paper and shone light through it and you had the positive,” Holownia explains. “Well, once I did that, I thought ‘I’m in love with this process,’ and I never went back. It fit me. It fit the pace of my life. It fit the way I wanted to work. I’m making deliberate images.”

The view camera rewards a deliberate, recursive approach. Holownia describes driving around the Tantramar region, seeing an idea for a photograph out his window, but sensing that something is missing. The light is off. A tree tries too hard to pose. Returning to the same spot a few weeks later, the photograph emerges, fully formed.

Holownia’s photographs are somehow able to express the accumulation of moments behind them—negations of the negative, though such phrasing feels incommensurate with their magic.

“What I love about the view camera is that there’s a duality of vision,” Holownia says. “It’s like sitting on a landscape with a pair of binoculars. You can capture the detail of the minutia as well as the overall atmosphere.”

In another large-scale project, Thaddeus Holownia photographed parts of the 568-kilometre-long Sable Gas Pipeline. This photo from 1999 is titled Anatomy of a Pipeline, KM 108. Image: Courtesy the artist.

In another large-scale project, Thaddeus Holownia photographed parts of the 568-kilometre-long Sable Gas Pipeline. This photo from 1999 is titled Anatomy of a Pipeline, KM 108. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Holownia did not need a pair of binoculars to locate the material for his Sable Gas Pipeline photographs of 1999 and 2000. He had maps—more than 50 pages of them. The enlarged 11-by-17 maps plot the Sable Gas Pipeline, a 568-kilometre segment of the 1,101-kilometre Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline owned by Spectra, Emera and Exxon.

The subsidiary overseeing the pipeline refused Holownia’s initial request to photograph its construction. They invited him to attend media events and provided him with press credentials. At the first event he attended, in Amherst, Holownia struck up a conversation with some of the engineers about their enlarged maps. He asked if he could have copies, and was given a blueprint of the entire project.

With the blueprint, a safety vest, and his camera equipment in tow, Holownia travelled to building sites along the pipeline and photographed evidence of the workers’ presence. A ladder, spit up from the ground, peeks at piles of dug-up soil. A portable restroom tips towards the woods, as if losing its balance.

The viewer has to squint to see the security fence wire in KM 185. A tree falls into a clear-cut lane, a reminder that those who put up “No Trespassing” signs like the one in the foreground are the ones who have trespassed.

As with KM 185, each photograph in this series derives its title from its place on the pipeline’s map. In this way, the images invoke and disrupt the incremental logic of the pipeline. By showing the artifacts and evidence of human presence, Holownia manages to highlight intervention as opposed to construction, rupture as opposed to progress.

The Sable Gas Pipeline photographs are a rare example of colour in the exhibition. Holownia started photographing the pipeline in black-and-white, but soon switched to colour. The result is a palette of a particularly devastating form of Anthropocene denial. The orange paint and yellow tape attempt to disguise a permanent transformation as temporary.

“It was this methodology of measuring the landscape to bury something,” Holownia says of his decision to use colour to highlight the artifacts of intervention. “And then when you’ve buried it it’s like this serpent that they’re burying along the way.”

The 16 Sable Gas Pipeline photographs hang on a wall next to four Sable Island ones from 1988. The suggestive juxtaposition summons a time before the pipeline. In one, the circular hoof-prints of a wild Sable Island horse simultaneously fade into the beach’s horizon line and walk out of the bottom of the photograph, as if the animal knows in advance to exit the scene.

Thaddeus Holownia, Beach Motel, Bar Harbour, Maine, 2015. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia, Beach Motel, Bar Harbour, Maine, 2015. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Holownia’s photographs can also be playful about the nature of human intervention. Beach Motel, Bar Harbour, Maine (2015) shows a kitschy beach fresco beneath a sign that reads “The Beach”; the sign is posted on the office of a motel located near an actual beach. A giant sandbox even extends into the parking lot from the base of the fresco. You can almost hear the kids clamouring “Are we there yet?” as the SUV pulls into the parking lot.

This photograph resonates with one from 40 years earlier, Bird Painting in Bushes (1976). The eponymous painting is of loons taking flight out of tall grasses. The real bushes appear to almost have grown up around the painting, like “the slovenly wilderness” in Wallace Stevens’ 1919 poem “Anecdote of the Jar.”

Holownia’s periodic collaborations with writers and poets testify to a mature understanding of these many facets of representation. Icarus, Falling of Birds is his third collaboration with Thurston. He has also worked with poets Peter Sanger and Douglas Lochhead, and art historian John Leroux.

These collaborations are signposted on the walls of gallery, snippets of an ongoing conversation between Holownia’s photography and his interlocutors’ poetry and prose. This conversation frequently carries over into book form.

“I like the idea of collaboration very much, but I don’t want to collaborate where someone will get a bunch of images together and then they’ll find some writing and put the two together,” Holownia explains. “I’m much more interested in saying ‘I have this idea about something. How’d you like to participate in it?’”

For example, with Silver Ghost (2008), Holownia told Thurston he was keen to do a book about salmon rivers. Thurston turned out to be an angler. The two spent five years going out on canoe trips around the Maritimes and looking at salmon river landscapes. Their experience is communicated in the related book through Thurston’s five essays and Holownia’s suites of photographs.

Holownia publishes such books under the imprint of Anchorage Press, the letterpress outfit that occupies the basement of his studio in Jolicure, New Brunswick. The studio is built on the site of the poet John Thompson’s former house, which burned to the ground two years before Thompson’s mysterious death.

Thaddeus Holownia, Blind, 2009. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia, Blind, 2009. Toned silver gelatin print, 41.91 x 16.51 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

The most haunting image from Holownia’s “The Nature of Nature” exhibition is Blind (2009).

A dilapidated hunting blind stands in the middle of a clear-cut. It is a small, sinking vessel propped atop a messy ocean bed of bush and branch. The blind’s roof is collapsing, but its single window is stable, holding just off dead centre in the frame.

“I placed [the window] almost directly in the middle because it’s got this structure,” Holownia says. “Everything else is chaos in that picture except for that shape.”

Hunters no longer peer out the window for game. The shape remains, an urge to still see better amidst the devastation.

As Rob Nixon observes, “environmentalists routinely face the quandary of how to convert into dramatic form urgent issues that unfold too slowly to qualify as breaking news—issues like climate change and species extinction that threaten in slow motion.”

Perhaps the ultimate value of Holownia’s fulsome archive of close attention lies in just such a successful conversion.

Thaddeus Holownia, Rockport, NB, 1993. Toned silver gelatin contact print, 43.18 x 17.78 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Thaddeus Holownia, Rockport, NB, 1993. Toned silver gelatin contact print, 43.18 x 17.78 cm. Image: Courtesy the artist.

Geordie Miller is a poet. He is currently teaching a poetry workshop at Dalhousie, where he earned his PhD in 2015. His book Re:union was published with Invisible in 2014. He lives in Sackville, New Brunswick.

This article is part of Canadian Art’s year-long Spotlight on New Brunswick series, created with the support of the Sheila Hugh Mackay Foundation.

Thaddeus Holownia, Icarus, Falling of Birds (detail), 2017. Image: via Art Gallery of Nova Scotia Facebook page.

Thaddeus Holownia, Icarus, Falling of Birds (detail), 2017. Image: via Art Gallery of Nova Scotia Facebook page.