Quebec museums and galleries do not have a venerable history of including contemporary Aboriginal artists in their exhibitions. As a result, First Nations and Inuit artists working in the province are often better known in the rest of Canada and internationally. A recent wave of exhibitions presented at major institutions in both Montreal and Quebec City show signs that this is changing.

Initiated in 2012 by the commercial gallery Art Mûr, the Contemporary Native Art Biennial has the potential to play an interesting role in this long-awaited shift. The biennial includes practices from across North America. This year’s edition was organized in collaboration with the Stewart Hall Art Gallery, and included an off-site exhibition of Nadia Myre’s work at the headquarters of Cirque du Soleil (by appointment only).

“Storytelling” was the first major multi-artist curatorial undertaking for Michael Patten, the European/Cree artist from the Sakimay First Nation responsible for curating this year’s biennial. Drawing from a compelling mix of established and emerging practices, he produced an engaging presentation of works organized around a timely theme. Those who have been following the recent conflict surrounding the Canadian government’s First Nations Education Act will appreciate the way in which Patten’s curatorial choices foregrounded the clash between pedagogical practices rooted in Aboriginal worldviews and the Canadian education system as a state apparatus promoting liberalism, and by extension environmental degradation and colonialism, to say nothing of the legacy of the residential school program.

Highlights of the biennial included Adrian Stimson’s installation Beyond Redemption (2010), in which a stuffed and mounted bison appears to be teaching a class of pupils reduced to pelts draped over black crosses; Frank Shebageget’s magisterial Curtain of Beavers (2009), which explores the relationship between Native communities and the de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver float plane; and Michael Anthony Simon’s Faux/Real (Gold) (2014), in which the fragile complexity of an actual spider’s web is fixed with spray paint and gold mica powder.

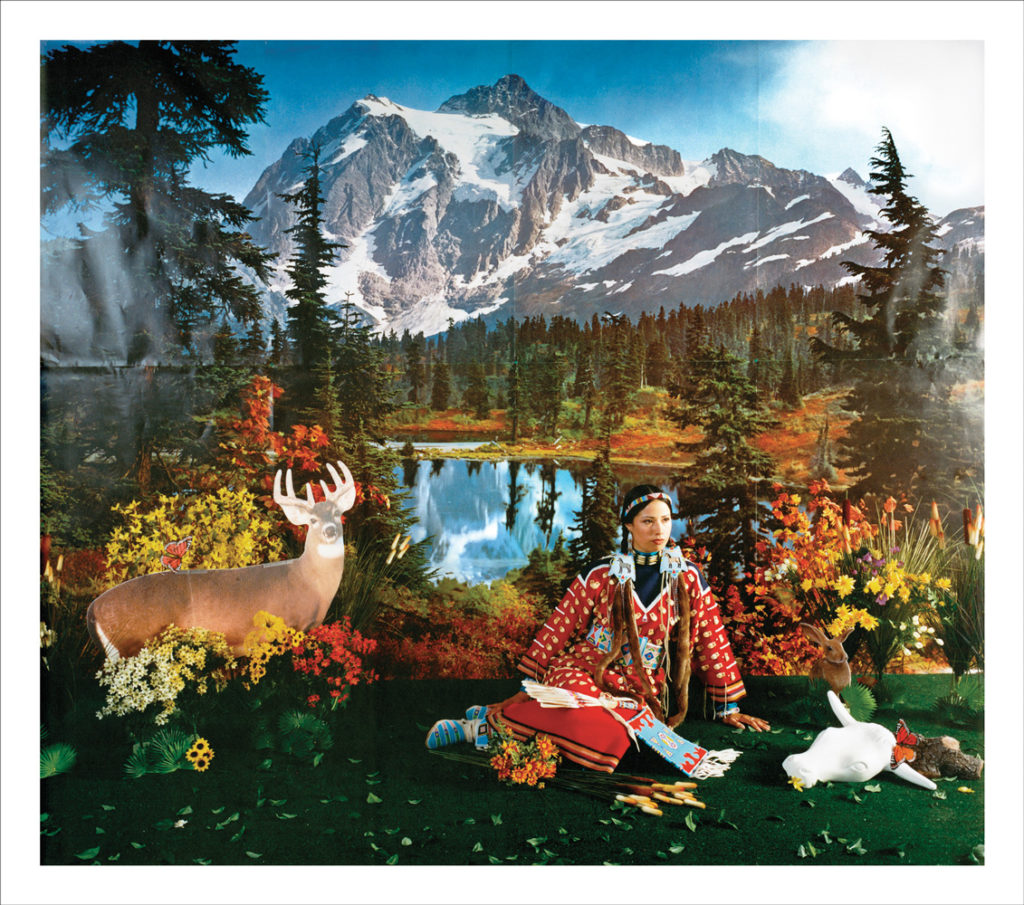

One of the most refreshing aspects of the biennial is its inclusion of less-recognized artists. Wendy Red Star’s Four Seasons (2006), a series of photographs satirizing dioramas of indigenous peoples found in natural-history museums, brings a new angle to an old critique, while Meryl McMaster’s series Ancestral (2008–10) probes similar issues through the projection of digital images of wildlife onto the faces of Aboriginal men and women—in this case, her father, Gerald McMaster.

Despite this wide range of practices, the biennial managed to remain focused, successfully highlighting the tension between individual and collective storytelling that motivates so many contemporary Aboriginal artists.

This is a review from the Fall 2014 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, view its table of contents.