Subtitled “Cross-Cutting/Inside Out,” this survey of works on paper served as an admirable measure of the arc of Renée Van Halm’s practice. The exhibition, which spanned the years 1979 to 2011, focused on one of her abiding interests: architecture. More precisely, it demonstrated her ongoing analysis of the ways our built environment, along with its furnishings and fixtures, both articulates cultural values and frames social interactions. Van Halm has explored this theme through a range of media—from installations that hybridize the disciplines of painting, sculpture and architecture, to handsome, large-scale canvases executed in oil or acrylic, to the gouache, graphite and pastel drawings and handmade collages on view at the Burnaby Art Gallery.

While her career has largely unfolded in Vancouver (where she has been based for the past two decades, much of that time as an instructor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design) and Toronto (where she taught at York University through the 1980s and was a co-founder and curator-director of Mercer Union), Van Halm has also logged serious time in Berlin (where she recently spent a four-year sabbatical). In each of these metropolitan centres, and in the many other places her travels and reading have taken her, she has used her keen mind and deft hand to analyze and deconstruct the architecture she has encountered. Her special, although not exclusive, concern has been modernist design, and her representational style (she often employs photographs as source material) is appropriately rearranged with dashes of abstraction and jolts of flattened perspective. Subtly, and mostly without the inclusion of figures, her art critiques the modernist movement’s original aspiration to improve the lives of the people who traverse its plazas, work in its offices, live in its houses and rest their bottoms on its low-slung chairs.

Van Halm’s work quotes liberally from modernism’s “tropes”: from the iconic vocabulary of Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Buckminster Fuller, Marcel Breuer and even the late Arthur Erickson, Vancouver’s demigod of drafty corridors and raw concrete. Her critical gaze scans across mid-20th-century apartment buildings, office towers, museums, galleries, houses and retail outlets from Tokyo to Chicago to Madrid. It also extends backward in time, to an annunciatory interior depicted in a painting by Fra Angelico, and forward, to the swooping, bulging, postmodern designs of Frank Gehry. In Bellevue Platz, Zurich (2004), an organically streamlined tram depot is posed in front of stiff 19th-century apartment buildings, suggesting the ways in which preindustrial form may function as an almost theatrical backdrop to modernism. As guest curator Sophie Brodovich writes in the exhibition catalogue, Van Halm’s work “exposes the extent to which the experience of architecture is mediated and framed by historical and social references.”

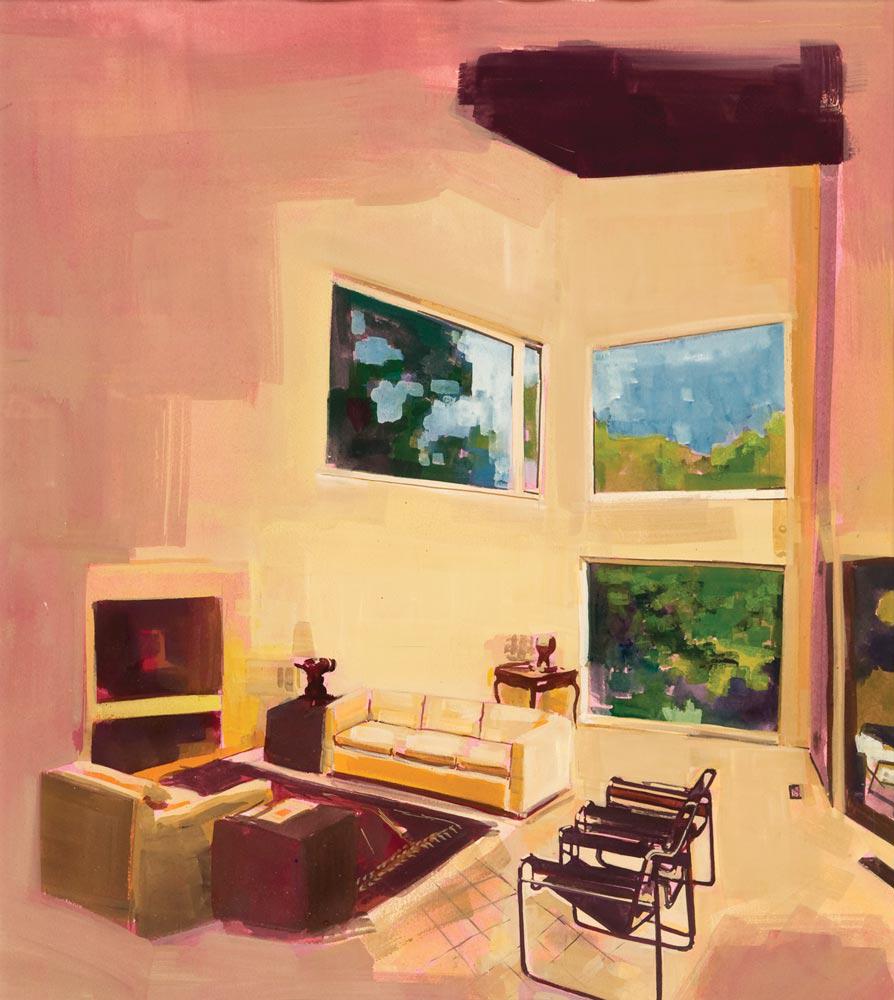

A series of interior scenes executed in the early 2000s alerts us to a notable paradox, the absorption of modernist design—especially furniture—from idealistic proposition into fetishized collectable. Here, Van Halm’s depictions of Eames chairs and Barcelona loungers seem to inquire whether modernism actually enhanced the lives of the many or the prestige of the few.

In her recent studies on paper, related to her series of paintings Reverse Engineering (2008–11), Van Halm overlaps and juxtaposes competing lines and grids abstracted from both interior and exterior views. A set of squared-off shelves may be superimposed over the horizontals and verticals of room dividers, then overlaid again on the partitioned facade of an office tower. In these works, the frantic networks of rectilinearity suggest a painful surfeit of modernism—an overwhelming ubiquity of straight-edged design, stripped of meaning and metaphor.