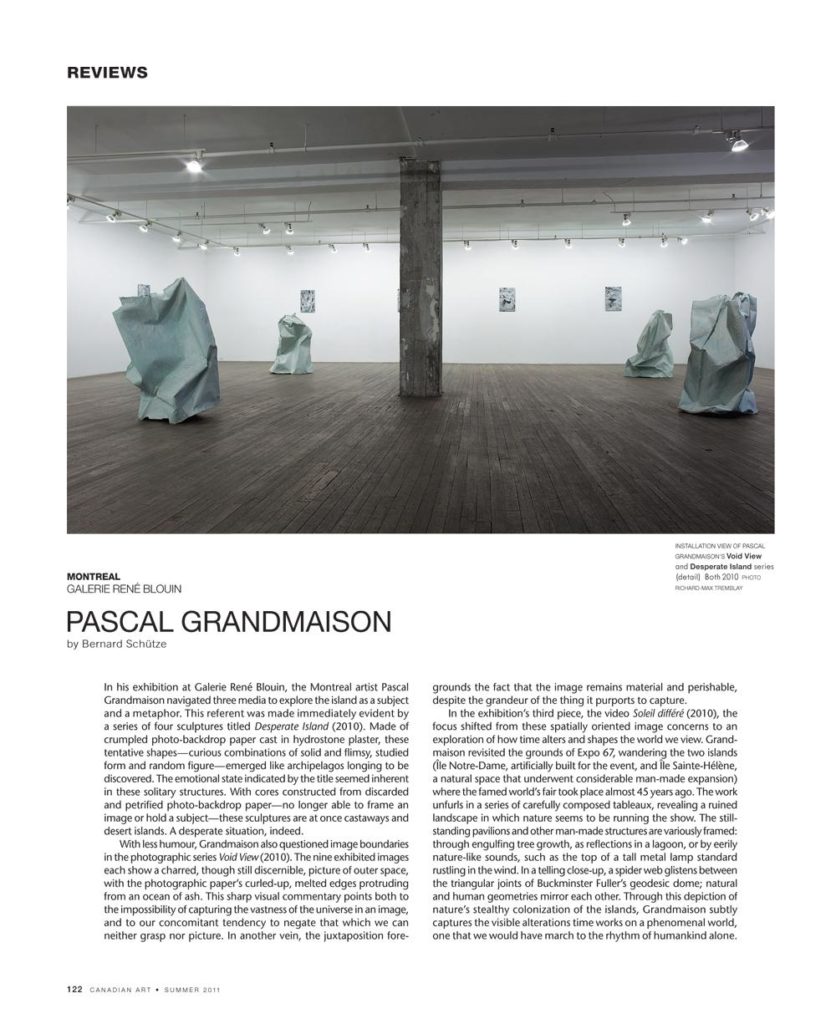

This referent was made immediately evident by a series of four sculptures titled Desperate Island (2010). Made of crumpled photo-backdrop paper cast in hydrostone plaster, these tentative shapes—curious combinations of solid and flimsy, studied form and random figure—emerged like archipelagos longing to be discovered. The emotional state indicated by the title seemed inherent in these solitary structures. With cores constructed from discarded and petrified photo-backdrop paper—no longer able to frame an image or hold a subject—these sculptures are at once castaways and desert islands. A desperate situation, indeed.

With less humour, Grandmaison also questioned image boundaries in the photographic series Void View (2010). The nine exhibited images each show a charred, though still discernible, picture of outer space, with the photographic paper’s curled-up, melted edges protruding from an ocean of ash. This sharp visual commentary points both to the impossibility of capturing the vastness of the universe in an image, and to our concomitant tendency to negate that which we can neither grasp nor picture. In another vein, the juxtaposition foregrounds the fact that the image remains material and perishable, despite the grandeur of the thing it purports to capture.

In the exhibition’s third piece, the video Soleil différé (2010), the focus shifted from these spatially oriented image concerns to an exploration of how time alters and shapes the world we view. Grandmaison revisited the grounds of Expo 67, wandering the two islands (Île Notre-Dame, artificially built for the event, and Île Sainte-Hélène, a natural space that underwent considerable man-made expansion) where the famed world’s fair took place almost 45 years ago. The work unfurls in a series of carefully composed tableaux, revealing a ruined landscape in which nature seems to be running the show. The stillstanding pavilions and other man-made structures are variously framed: through engulfing tree growth, as reflections in a lagoon, or by eerily nature-like sounds, such as the top of a tall metal lamp standard rustling in the wind. In a telling close-up, a spider web glistens between the triangular joints of Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome; natural and human geometries mirror each other. Through this depiction of nature’s stealthy colonization of the islands, Grandmaison subtly captures the visible alterations time works on a phenomenal world, one that we would have march to the rhythm of humankind alone.

This is an article from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Summer 2011 issue of Canadian Art