The “Francis Bacon and Henry Moore: Terror and Beauty” exhibition, currently on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario, is an assembly of works by two great British artists of the second half of the 20th century.

Francis Bacon and Henry Moore were exhibited together several times in the past—in the 1950s and 60s, even. The question is what this combination of approaches means to us today.

While Torontonians are familiar with Henry Moore’s oeuvre from the AGO collection, not to mention his sculpture at City Hall, this is the first major exhibition of Francis Bacon’s work in Canada.

Even so, however, Bacon should not be a complete stranger to the Canadian audiences: The 1972 film Last Tango in Paris, strongly influenced by Bacon’s vision, was banned for obscenity by the Nova Scotia Board of Censors in 1974. Also, the National Gallery of Canada owns one oil painting by Bacon, Study for portrait No.1 (1956), as well as a collection of related Bacon studio documents acquired following his death in 1992.

I’m always interested in people’s reactions to art, so I asked a few questions of a teenage girl standing with a group of friends in front of Bacon’s Seated Figure (1983).

“What do you think?,” I said.

“I kind of like it.”

“Why do you?”

“I don’t know.” Here, she hesitated for a moment. “It’s like a horror movie: nice, and colourful, and scary.”

“Scary like ‘I know who you are under the monster costume,’ or…..?”

She didn’t let me finish, bursting with certainty.

“No,” she said firmly, “it’s serious scary.”

In the 1989 Batman movie directed by Tim Burton, the Joker evaluates Bacon’s work in a similar way that this girl did.

In one scene, the Joker enters Gotham’s art museum with a gang of bad-ass followers armed with spray paint, paint in cans, and brushes. What follows (after everybody else has been rendered unconscious by poison gas) is a spree of vandalism that comes to a stop in front of Francis Bacon’s painting Figure with Meat (1954). Joker prevents one of his sidekicks from slashing the canvas and exclaims, “Hold it! I kind of like this one, Bob. Leave it!”

In this filmic moment, the Joker is a modernist par excellence: like Clement Greenberg, he wants his Kantian moment of revelation; he doesn’t want to think in front of a painting. The Joker knows that painting is a repository of long, historical and conceptual evolution of the medium and with his statement “I kind of like it!” he acknowledges his inner kinship with Bacon.

Just as its title indicates, that painting represents two hanging sides of meat on a dark background. In the lower middle, there is a figure with his mouth wide open. Perhaps the Joker can represent a radical curator who says, “Let’s forget the past. We start from right now, as if nothing ever happened before.”

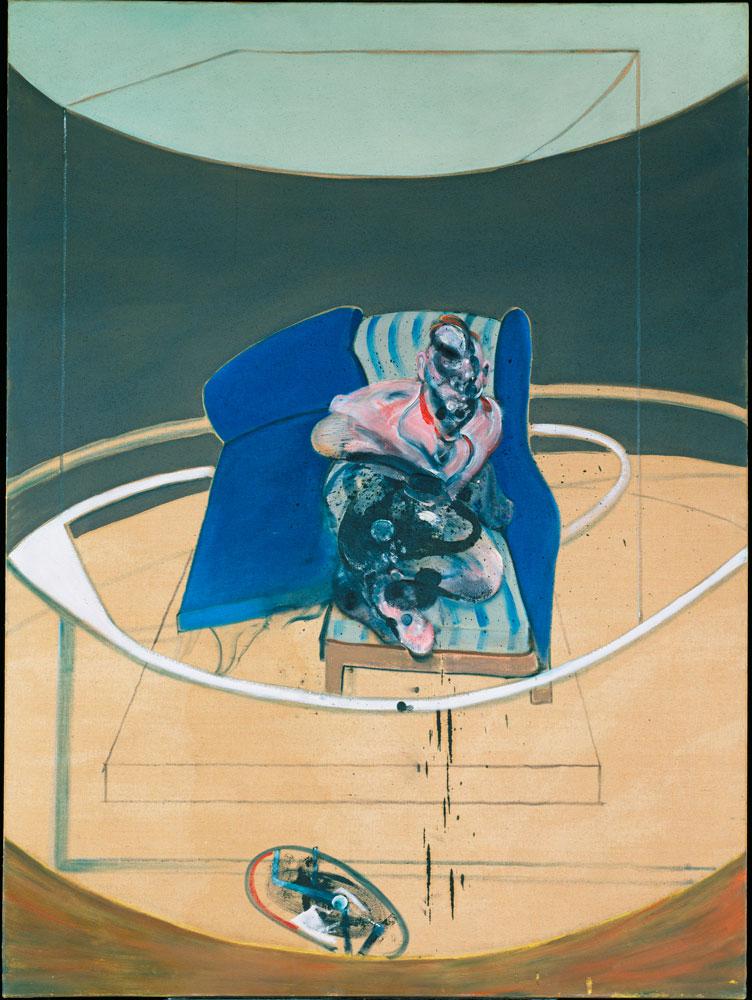

Bacon’s figures—whether on film or not—barely hold their form together. They leak, they collapse under their own weight, they find stillness in motion. Bacon’s subject, or rather what is left of it, is trapped in the world in which it is impossible to feel at home; and the world that never becomes a home is one of the definitions of hell.

While Henry Moore is still asking questions—and could ask, after Lev Shestov, “Why is it that people, so faultlessly able to describe and diagnose the illness, don’t show the least desire of treating it?”—Bacon is no longer interested. His soundlessly open mouths not only do not speak, it is as if they absorb sounds coming from the outside world.

Similarly, while Moore’s figures are sustaining themselves entirely from within, Bacon’s are disengaged fugitives from history. Bacon is already “after” when Moore is still “before.”

And while Moore’s nightmares are still rooted in anthropological concerns—corporeal and measurable—Bacon’s subject is a phantom without a name, without a past, because a collectivized subject is only and always an abstract fragment of a person.

But we need Moore’s confrontation with Bacon. Moore is a guardian of our sanity. His forms are stationary—despite the refined movement of all their structural lines, and their impeccable pronunciation of architectural tempo, as well as their perfect formal economy, they are going nowhere.

And because of Moore’s immobility, tactility and measurability, I welcome his presence with relief. He defends us from Bacon’s radical, cinematic mobility, forever escaping our grasp.

Bacon’s state of convulsive stasis is an illusion, because looking at his canvas you have an impression that between the two or three takes, there are more frames, as in a movie, trapped in the same space. There is also a sense that this trapping of multiplicity is not a conscious choice, but the consequence of there being nowhere else to go.

Bacon is the scandal of the flesh, the existential strip-tease—even a post-flesh, post-body concept of a person. He is a fugitive, and his natural state is motion, appearance and disappearance. He belongs to non-materiality, to cyberspace—and this is his paradox, because together with the sensuality of his pictorial matter, the materiality of subject is gone. That’s why Bacon is so relevant today.

I wouldn’t want to be in the shoes of this exhibition’s curator, Dan Adler. Like every exhibition showing art of such caliber—where honesty is unbearable and full of taboos which we would rather not face—any attempt to domesticate dark thoughts is futile.

The exhibition is elegant and systematic; Adler seemed to sense that no conceptual scaffolding is equal to the rage trapped in Bacon’s works. His subtle device—of regulating collective attention by providing pointers along the way—is helpful in diffusing the perception of the abyss which opens up in front of our feet as soon as we confront Bacon’s dark vision.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait on Folding Bed, 1963. Oil on canvas, 198.1 x 147.3 cm. Tate Britain, London © Estate of Francis Bacon / SODRAC (2014).

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait on Folding Bed, 1963. Oil on canvas, 198.1 x 147.3 cm. Tate Britain, London © Estate of Francis Bacon / SODRAC (2014).