I’ve known Martin Kippenberger’s work for quite some time. One of the most remarkable things about “sehr gut | very good,” a major exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof, is that I now feel as if I know the man. With minimal didactic intervention, curators Udo Kittelmann, Britta Schmitz and Miriam Halwani offer a potent sense not only of the development of Kippenberger’s aesthetic preoccupations (which were varied, to say the least), but also of Kippenberger himself. Such is the communicative power of his art.

He has almost entirely taken over the museum: his paintings, drawings, sculptures and performances—to say nothing of the Falstaffian personality they channel—fill up the exhaustive length of the main exhibition space, and two special installations squat in other, smaller wings of the museum. Taken altogether, one emerges from the Hamburger Bahnhof with a more or less complete picture of an artist who has, through his own aggressive self-mythologizing and (more importantly) through his aggressive skill, emerged as one of the seminal figures of contemporary painting.

As a painter and as an artist, Kippenberger tore through styles and modes (although, even at his most abstract, he never entirely sloughed off the mantle of figuration): thick impastos, thin washes, haptic expressionism. Kippenberger’s approach to image-making was voracious, promiscuous and indignantly irreverent. Consider Kippenberger in counterpoint to Gerhard Richter, another German giant of contemporary painting. Kippenberger was young enough (had he not died of liver cancer in 1997, he would have been 60 this year) to feel the yoke of Richter’s influence as he came of artistic age. Throughout “sehr gut,” you can see the younger artist chafe against the previous generation’s meditative conceptualism (Kippenberger, in fact, once bought a Richter monochrome, and promptly turned it into a coffee table). To see evidence of kinship with more visceral artists like Mike Kelley seems a natural logic. Whereas Richter and his contemporaries used painting to evince a philosophical distrust of image creation and consumption, Kippenberger’s relationship to painting (and artmaking in general) seems to be that of an abusive lover: something sexy to twist, bend, slap around and reshape according to his needs.

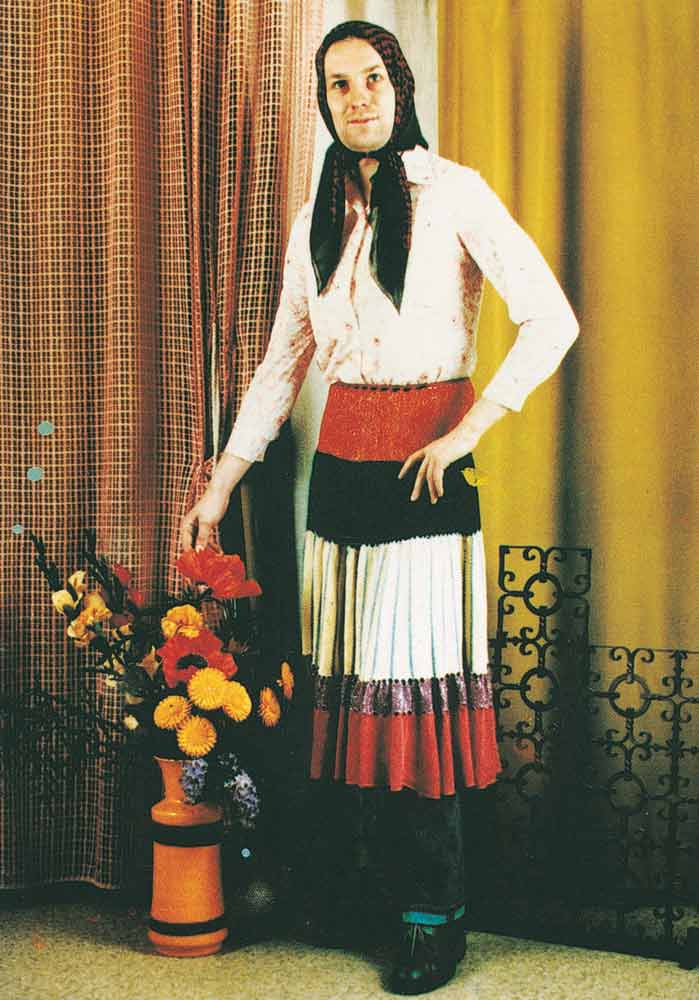

Of course, Kippenberger was equally abusive when it came to his own image. He was a relentless self-documenter whose hubris was always underscored by a kind of sad irony, which only grew more pungent as time progressed. An untitled 1981 painting from the series Lieber Maler, male mir—a series which he hired a commercial artist to paint—is a snarl of pugnacious politics and rock-star pomp. Decked out in a cowboy hat and a fur-collared coat, hands akimbo underneath a wide banner emblazoned by the all-caps word “SOUVENIRS” and flanked by two DDR insignias, Kippenberger makes caustic reference to the political absurdities and socio-economic disparities emblematized by the Berlin Wall. But he is also asking you to remember him in furs and a cowboy hat, like a fop-Euro Peter Fonda from Easy Rider.

As he aged, and the excesses of his hard-drinking lifestyle took their toll, he preferred a more comic-tragic mode: a paunchy clown with oversized underwear pulled up over the expanse of his swollen belly like a diaper. Towards the end of the show, Kippenberger is photographed re-enacting the poses from Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. In the delicate black and white pictures, he projects a pleading, baroque fragility. But in the paintings based on these photos, he distorts himself into lurid colours—fogs of acrid greens and gouty reds—and exaggerates all of his bags and sags. It’s not self-laceration (which is the dark twin of self-aggrandizement); there is still a tenderness to his brushmark and a caress to his line. The artist is taking honest stock of his own self-inflicted ravages.

The garrulous productivity evidenced by “sehr gut” makes one wonder what Kippenberger would be up to were he still alive. What would he make of the critical resurgence of interest in painting in the early 2000s, a resurgence that claimed him as a central hero? He was so combative with his own influences: an Oedipal resentment of Picasso, a junior sibling’s irreverence for Richter; what kind of older brother would he be to painters like Neo Rauch? His response to the previous generation’s artists’ processing of the Second World War was a curt “Heil Hitler, You Fetishists,” delivered as both the title of his 1984 painting Heil Hitler, Ihr Fetischisten and the acronym “HHIF” painted in it; how would he digest the current political climate? What bullish response would issue forth from Kippenberger’s jocular, aggressive, impish and furiously intelligent brush? It is the signal victory of “sehr gut” that it provides, with clarity and focus, a wealth of information—certainly enough to be able to hazard a guess.