Landon Mackenzie says that when she was invited by the Vancouver Art Gallery to participate in an exhibition with Emily Carr, she wanted “a two-woman bake-off”—equal representation by each artist, historic and contemporary. In the end, 30 works of Carr’s hung beside 21 of Mackenzie’s, and the latter’s playful remark belies the profound respect and critical acuity she has brought to the project. Mackenzie deeply researched Carr’s life and art and looked intently at each original Carr work she chose to exhibit with her own, finding formal and thematic correspondences between them. Despite obvious differences in style, content, origins and era (Carr was born in Victoria in 1871 and died there in 1945, nine years before Mackenzie was born on the other side of the continent), a dialogue has been established here that is philosophically and aesthetically engaging—and deeply moving.

In the show’s catalogue, VAG curator Grant Arnold describes Carr and Mackenzie’s “shared interest in using the landscape as a structure for examining problems of representation and expression.” He also asks us to think about “their struggles as women in a tradition of art making that has been largely defined by male artists.” Mackenzie’s subtitle for the show, “Wood Chopper and the Monkey,” alludes directly to those struggles. It also references two quite distinct works, her large painting Wood Chopper and Paradigm (Canadian Shield and Target Series) (1990) and Carr’s small oil sketch, Woo (c. 1932), an image of her beloved Javanese monkey. The former work is Mackenzie’s highly charged response to theoretical proscriptions against painting that she encountered in the early years of her development as an artist. It depicts a cartoon-like young woman, naked except for a tool belt slung around her hips, axe raised high over her head, about to—what?—cleave, split and sunder the pile of huge logs that lie across her path. Toothy bars of masculine abstraction border the composition on the right and a large black diamond shape hovers at the work’s centre, above the barricade of heavy, phallic forms. The sharply pointed diamond suggests the kind of wedge used in felling trees or splitting logs while also functioning as a symbol for the paradigm of the title. At the same time, it evokes what Carr scholar Gerta Moray describes in her eloquent catalogue essay as the “threatening vaginal void.” Mackenzie worked as a life model while attending the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and although this and other autobiographical references are embedded in her painting, it’s notable that, in the context of the exhibition, she came to see the wood chopper as an apt metaphor for Carr. In an interview with Arnold, again in the show’s catalogue, Mackenzie asserts that Carr “cleared a path that made it possible for my generation to have the careers we do. And she has shaped a vision of the coastal forest in many imaginations.”

Carr’s painting of Woo, wearing a little yellow dress, standing on a tree branch and peering at some unseen point in the distance, was not available for loan to the VAG. Because it was important to her understanding of Carr, Mackenzie created her own version of the work, duplicating Carr’s composition and aspects of her palette and paint application but bringing into being a shorter, more compact and somewhat more melancholy monkey. Instead of regarding Woo as a symptom of the historic artist’s oddness and eccentricity, Mackenzie presents the creature in the context of Carr’s communion with the natural world, her deep connection to her animal companions and the meaning of that connection. Mackenzie, who has three children, sees that the relationship between Carr and Woo approximated that of a mother and daughter, but she does not belittle it (as many sexist critics and historians have done). Instead, she honours it and meditates on its burden of longing and inevitable loss. Mackenzie has also used the act of recreating Woo as a means of examining issues of copying versus homage and appropriation versus inspiration, particularly as they relate to Carr’s depictions of Northwest Coast First Nations art.

Mackenzie decided that she would focus on Carr’s later works, produced during the 1930s when the historic artist was “old.” To her surprise, she discovered that, in 1930, Carr was 59, her own age—and with her best work ahead of her. The exhibition was organized thematically into three major groupings in three separate galleries, with a transitional section of drawings hung in a hallway between the first and the second. Narrative elements and subtly cross-referenced strands of chronology and biography emerge through the show, underscoring what possibilities have been available to women artists, then and now. (Mackenzie is descended from a long line of artists: her great-grandmother attended the Académie Colarossi in Paris around the same time Carr was studying there.)

The first room includes selections from Mackenzie’s Lost River series of paintings, produced in Montreal in the early 1980s, along with a couple of small paintings made in 1982 while Mackenzie and her life partner were living and working as self-described “bush hippies” in a tent in the Yukon. (Yes, Mackenzie did chop wood.) These are juxtaposed with four major Carr canvases, including Big Raven (1931), which speaks to the historic artist’s identification with the solitary creature perched atop a pole in an abandoned First Nations village, amid a swirling sea of dark green foliage. Carr’s interpretation of the crest figure is comparable to the symbolic role played by the hybrid animals—part wolf, part caribou—that appear in Mackenzie’s Lost River paintings. These hybrids serve as human surrogates in twilit northern landscapes, symbolically registering industrial encroachment and environmental contamination.

Mackenzie also poses her explorations of landscape-based abstraction (including an homage to Rita Letendre) against the faceting and volumetric lessons of Cubism that Carr was absorbing (through the example of Lawren Harris) 50 years earlier. A big, dark, mountainous hump in Carr’s Vanquished (1931), echoes, in ways both formal and mystical, a big, dark, mountainous hump in Mackenzie’s Lost River Series No. 16 (1982). Both artists seem to be negotiating a new relationship with the natural world on the surface of a canvas, reimagining how the landscape subject might be represented.

In the second gallery, where both the Woo and Woodchopper paintings are installed, Mackenzie grapples with ideas of longing, self-representation and self-determination. In a self-portrait dating from the mid-1920s, Carr depicts herself from behind, sitting in a chair in front of an easel, painting. Fully clothed, of course. In many ways, her strategy is the spectral opposite of Mackenzie’s full frontal, axe-wielding self-portrait, although both works address what it is to be a woman painter in her own time. The Carr self-portrait was made when her spirits were low, before she had been “discovered” and validated by male artists and curators. It is certainly antithetical to the bold, outward-looking Big Raven in the first gallery, although Carr’s 1924–25 pose is oddly reiterated in Laughing Bear (1941), also thought to be a self-portrait.

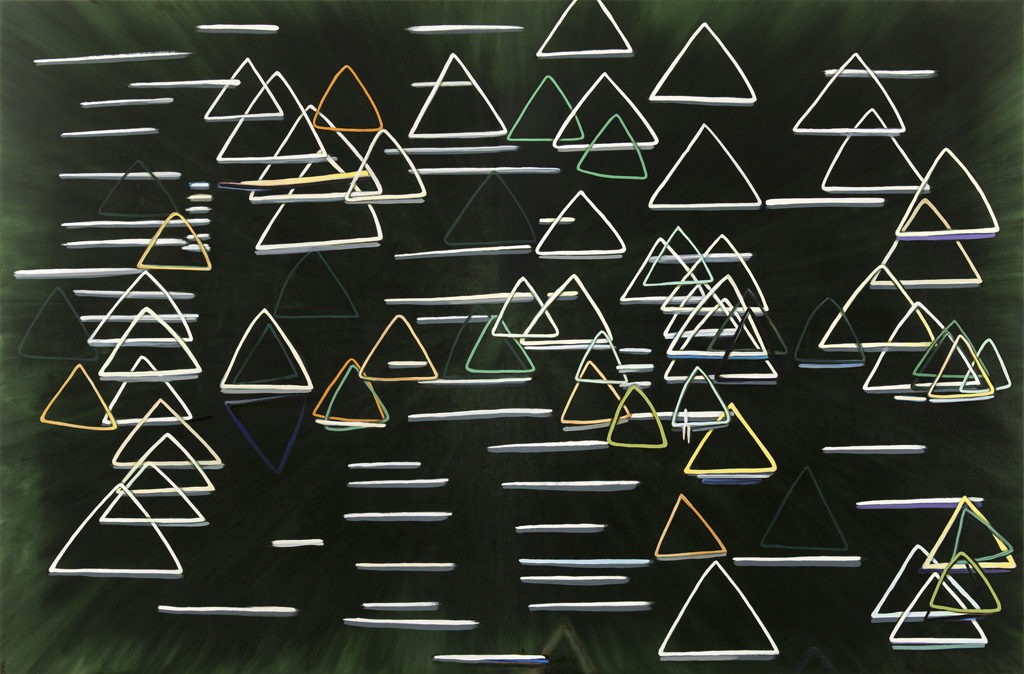

The third gallery is the most mysterious and introspective, encompassing illness, death and transcendence. (Moray characterizes this room’s theme as “dissolution.”) Here, Mackenzie’s paintings employ repeated formal devices, such as triangles, that find resonance in Carr’s deeply spiritual Grey (c. 1929–30) and Old and New Forest (1931–32). Mackenzie’s works also reveal the shifting, shimmering strands of existence that connect our inner worlds—physical and metaphysical—to the vast cosmos. Her large canvas North Star/Neurostar (2013), is exactly that: an orb radiating multiple, slender lines of light and colour—a nexus of nerve fibres or a pulsing heavenly body—in a deep-blue night sky, sprinkled with distant stars that somehow resemble tiny television screens or computer monitors. Floating near the bottom of the painting is a slightly larger screen of light, a portal into another universe perhaps, which speaks both formally and metaphorically to doorways imaged in Carr’s Old Time Coast Village (1929–30).

Carr’s work poses an imaginary First Nations village, seen from a distance in front of a vast, deep forest. It’s a forest whose trees, like immense, abstracted cones, march forward towards the viewer and also backward, into darkness and the unknown. The effect is of a long, low stage set, all but overwhelmed by the towering painted backdrop behind it and the heavy curtains which threaten to close in front of it. Except for the prow of a canoe, poking up into the picture frame at the very bottom of the composition, the village looks deserted, its buildings a ghostly white, its poles stripped of crest figures. Mackenzie has picked up on this appearance of abandonment in a major abstraction she created explicitly for the exhibition, Big Pink Sky (TB). The painting’s gorgeous splatters of pink and red initially suggest joy and vibrancy, until you realize that their underlying reference is to the blood and sputum coughed up by tuberculosis victims. Mackenzie’s painting evokes the devastation caused amongst First Nations peoples by European diseases while also calling up Carr’s own losses: her beloved mother and her only brother both died of tuberculosis. Carr’s “old time” village is a real-time graveyard.

Mackenzie’s choices of Carr’s works and the correspondences she establishes with her own are both intuitive and reasoned—they make sense to the gut and to the brain of the viewer. What is also true here is that they make sense to the eye. This is a beautiful show.

Afterword: Last fall, I was introduced to an esteemed Quebecois filmmaker who was shooting some footage outside the Vancouver Art Gallery. When he heard I was an art critic, he joked that there was yet another Emily Carr show on—that every time he was in Vancouver, the VAG had an Emily Carr show on. Although I faked a chuckle, I felt like responding, “You have a problem with that, buddy? Get over it!” To me, it is a given that Carr should be honoured here (the VAG houses the Emily Carr Trust and its own huge collection of art by the West Coast’s favorite daughter; produced the show under review; and hosted a recent invitational Emily Carr forum), there (a big, expensive and widely acclaimed show of her paintings and drawings that launched at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London in November and is set to open at the Art Gallery of Ontario in April) and everywhere. All Emily Carr all the time.