How do you paint absence? This is the formal and conceptual problem that US artist Kerry James Marshall set for himself early on—“to call attention to the absence of black presence” in visual art. Entwined with this was another aim: getting authentic representations of black culture accepted into an exclusively white visual-art tradition such as Western painting.

Marshall grew up in the late 1950s and 60s in Birmingham, Alabama, and South Central Los Angeles, California, hotspots of the civil rights movement. While demonstrators in these places were being shot with water cannons and bullets, Marshall absorbed their political consciousness as a child, and later worked to develop tools for another sort of power—that of visual representation.

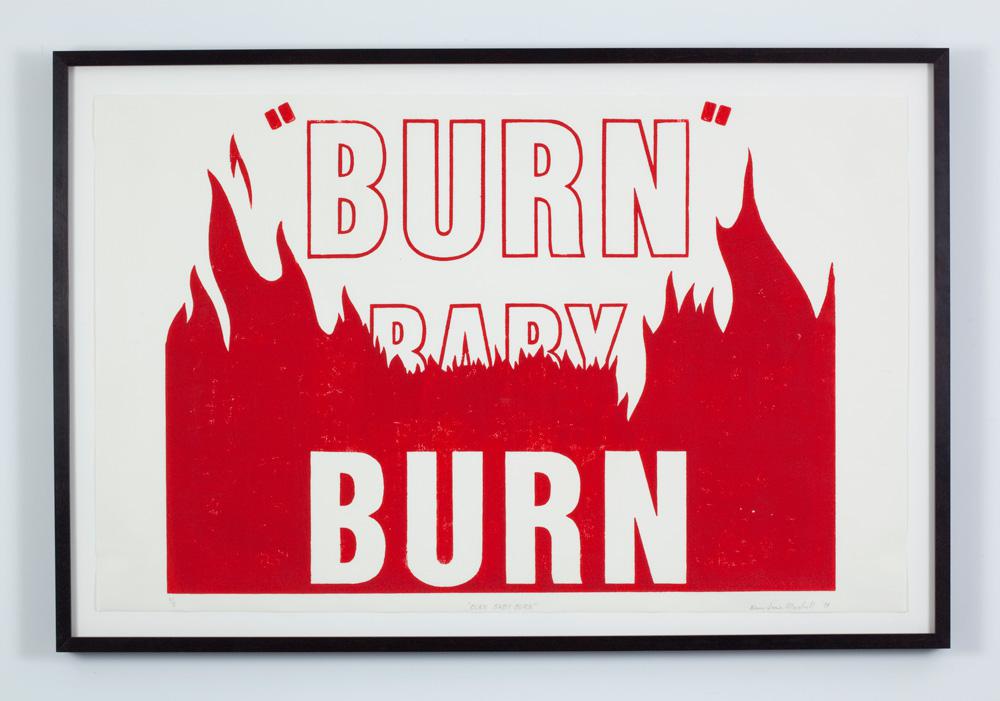

In the 1960s as well, some contemporary white artists engaged in a “crisis of representation” were rejecting the established art system. Yet for many black artists just entering the game, the term “crisis of representation” meant something quite different: changing the fact that they quite simply did not see themselves and their cultures sufficiently represented in the arts. One result was the Black Arts Movement, an aesthetic arm of the Black Power movement, which ran from roughly 1965 to 1975.

Marshall, who studied at the Otis College of Art in the mid 1970s, was informed by the Black Arts Movement and thought that the real crisis at hand was the “the lack in the image bank” of black subjects. Rather than abandoning the museum, he wanted to bring black artists in.

“I keep making pictures that aim to make their way into these museums,” Marshall has said. “When one day the Prado will start collecting contemporary art, I want to be in a position to have one of my works considered.”

Marshall hasn’t seen his work in the Prado yet, but he’s close. His mid-career retrospective “Kerry James Marshall: painting and other stuff” is installed nearby in Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofia, as well as at Barcelona’s Fundació Antoni Tàpies. Already celebrated for his painting, it is the “other stuff” of the exhibition title—collage, video, photography, installation, and comic-book graphics—that the curators thought to elevate here.

Unifying all of Marshall’s chosen art forms is his process of “amalgamation” of multiple languages drawn from a shopping catalogue of styles—from high to low art, from across time and place, including European, Japanese, American, and African-aboriginal and -diasporic arts and cultures. Among his subjects are the reverberations of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the neglected history of black resistance, the everyday reality of African Americans (beyond the tropes of exotics or victims), and their potential for a better life.

Marshall’s mix of media is shared between the two museums, though most of the paintings are found in the larger Reina Sofia venue. Many of the artist’s forays beyond painting are successful, but Marshall has spent most of his career with paint, and that is what shines brightest.

The paintings are generally either large, narrative tableaux in the style of “grand manner” history paintings or smaller portraits of varied dimensions. His canvases are sometimes layered with paper before painting, giving them the glossy appearance of early Renaissance wood panels. Imagery such as book covers are collaged into selected canvases, along with stencilled impressions of roses.

Marshall’s signature stylistic innovation has been his emphatically black bodies. While struggling with the problem of how to represent black figures within narrative painting, a genre that offered few to no such models, he recognized Ralph Ellison’s description of invisibility from Invisible Man—the condition of, as Marshall has put it, “being and not being, the simultaneity of presence and absence.” Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self (1980) shows a black silhouetted figure with white grinning teeth, eyes and shirt collar—a kind of blackface caricature—with the pale elements popping out against a nearly black background.

Renaissance painters developed realist techniques, such as chiaroscuro to suggest volume, for their mostly white subjects. Marshall renews that incomplete project to include bodies largely excluded from those historical pictures, and has developed varied techniques for painting black skin. Sometimes, light reflects off his black faces as stylized stars; elsewhere, light is absorbed seductively as deep, purpley tones.

Both of these techniques are seen in Black Star (2011), along with themes of resistance and freedom. A very black, very real woman breaks through the abstract surface of a Frank Stella–inspired, star-shaped design that also evokes the early-20th-century Black Star Line that offered newly liberated African-Americans passage back to Africa.

Marshall’s purpose is partly rhetorical, as he makes the early activists’ slogan “Black is Beautiful” even more emphatic and concrete. But he is also deeply committed to a craft traditionally tasked with beauty. Indeed, his rich palette of greens, reds, and pinks set off against black, velvety figures is both celebratory and strikingly beautiful.

Another Marshall feature is his mixing of perspectival systems, so that realism, flattened space, stylized pattern, and symbolic elements share one pictorial space. In Slow Dance (1992—93) a man and woman, deeply black other than the whites of the woman’s eyes and her fingernails, stand in statuesque embrace in a living room that shares the wonky perspective of Van Gogh’s bedroom and the flattened space and expressionist colour of Matisse’s red studio. On a table coated with Haitian Vévé markings stands a bottle and an Ebony magazine that, like Cezanne’s still-life fruits, stay miraculously put despite their perspectival instability. As in early medieval, or even Egyptian, images, a textual register is added into the visual—a banner of musical score and the words “BABY I’M FOR RE-AL” float lyrically above the couple. Primitive masks watch over them protectively, and pink and red stencilled roses on the wall promise hope.

Some of the painted portraits recall at once Byzantine icons, Flemish portraits, Pop art screenprints and primitive sculpture. Lost Boy: AKA Black Johnny (1995) commemorates the many inner-city African-American children who lost their lives in gang wars or were incarcerated through police profiling. Around the intensely black face, a halo, golden rays and delicately patterned stencils of pink and white suggest sacrificial loss. The features are stylized, as with carved wooden masks, yet appear realistic. A Jackson Pollock drip of white paint falls just above the saint’s sad eye.

Marshall has extended his experiments with dark tonalities beyond painting into photography with his recent UV light portraits. In Untitled (Cheryl) (2012), a seductive darkness envelops his reclining subject in soft, understated tones.

In a contrasting mode, Marshall’s inkjet collage of found photographic imagery titled Heirlooms and Accessories (2002) examines a shameful, not so distant past. Against the faintly visible scene of a crowd at a 1930s Indiana lynching, the faces of three white women looking directly at the camera are isolated and framed by medallions on chains. Avoiding a simple reiteration of a shocking historical image, Marshall considers the power structure that subtends it—that is, how power and wealth were acquired by the chaining of Africans, and also how power and wealth have been passed down through generations of privileged whites.

Marshall has been applying an increasingly complex repertoire of styles, media and conceptual materials to his powerful interventions in the politics of aesthetics. Let us hope that at least some of those explorations continue to be carried out with paint.