If you like breasts, you’ll hate Lee Miller’s Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Mastectomy) (c. 1930)—which is the point of this photographic diptych, a highlight of the landmark exhibition “In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States.” Organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderno, the exhibition is now on view at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

Visiting a friend who had just had a mastectomy, Miller absconded with the cancerous, recently amputated appendage, placed it on a plate, then photographed it from two angles. Characteristically surrealist, this simple move shifts the naked breast from attractive to repulsive. Yet given surrealism’s view of women as muses—confined to a pedestal, perhaps—Miller’s shift critiques surrealism from within.

Forceful and discomfiting, this work underlines what makes “In Wonderland” a must-see. Artists like Miller, Louise Bourgeois, Frida Kahlo, Yayoi Kusama and Louise Nevelson give this show a blockbuster’s heft—a weightiness that its chunky, well-illustrated catalogue emphasizes, with chapters by experts like Dawn Ades and Whitney Chadwick. Yet, unlike most blockbusters, this one does more than recycle hits. It uses its impressive array of artists and works, famous and less familiar, to reassess one of modern art’s key movements.

“The history of women in art—the inventory of all the contributions made by women artists through every period and in every discipline—remains to be written,” says Consuelo Sáizar in the catalogue. “Concealed, marginalized, undervalued and often openly disdained, women artists have had to travel an arduous path to find the proper recognition for their work.” And “In Wonderland” supports that claim. This art, while powerful, remains in the shadow of surrealism and its aftermath.

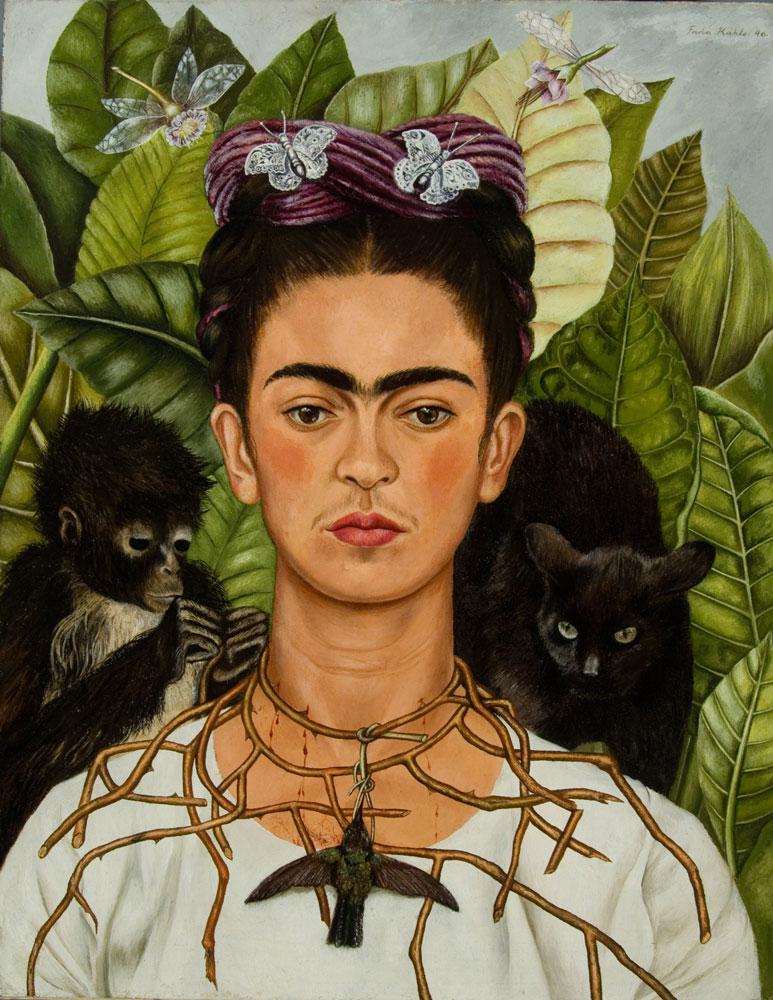

One standout here is Miller: her severed breast, her heartfelt portrait of Joseph Cornell in profile (1932), her quietly seething Untitled (Saint-Malo Boot) (1944) with its bullets snaking out from an abandoned boot on shattered cobblestones. Equally gripping, Kahlo’s collage Mi vestido cuelga ahí (My Dress Hangs There) (1933) breaks from classic Kahlo despite the autobiographical theme. For example, the paintingAutoretrato con collar de espinas y colibri (Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird) (1940)—also here—uses Kahlo’s characteristic stripped-down depth and accessible iconography of her broken body. By contrast, Mi vestido cuelga ahí—while not recondite, with its teeming masses in the foreground, images of church, state and industry mid-ground, and the Statue of Liberty above—inclines toward social realism rather than the lightly done magic realism more typical of Kahlo. Complicating things further, these images lie behind a brown and green dress suspended between a toilet and a trophy. But the nod to Duchamp (“The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges,” he wrote) plays against the masses below that gather into Kahlo’s dress: here is Kahlo as Marianne.

Beyond celebrating icons like Kahlo and Miller, “In Wonderland” emphasizes its theme’s continuing relevance. Several artists contemporary with surrealism’s vanguard died only recently: Louise Bourgeois in 2010, Leonora Carrington in 2011, Dorothea Tanning just this year. The American painter Sylvia Fein remains active, as does Kusama (whose retrospective, now at the Whitney, launched at Tate Modern this winter).

Equally interestingly, some of this art still feels current: Lola Alvarez Bravo‘s photomontages and the Italian-born artist Bona’s abstracted landscapes from the mid 20th century: even more so, Francesca Woodman‘s photographs from the 1970s. It helps that, although Woodman died in 1981, she was born in 1958: she matured as an artist contemporaneously with Cindy Sherman and Roger Ballen, not Max Ernst and Man Ray. And we see a convergence of sensibility with these contemporaries in monochrome photographs like Splatter Paint, Rome(1977–8)—where paint splashes across a mottled wall and over a partial figure exiting stage left—and Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island(1975–8), with its ghostly figure protruding from the pantry of a decrepit interior. But it’s also revelatory viewing Woodman in this company, to experience her full potential (photographs like Self-Portrait Talking to Vince, Providence, Rhode Island (1975–8) are weaker).

The narrowness suggested by this show’s subtitle—“The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States”—understates the exhibition’s reach: many of these artists migrated to the States from elsewhere, and all had international links. So “In Wonderland” delves deeper than its title suggests. And seeing this show alongside the Musée national’s displays from its collection of Jean Paul Riopelle and of Quebec art from the 1940s to the 1960s adds salutary context, this province being where surrealism had its deepest North American impact, and the results remaining similarly under-recognized internationally.