This year’s dOCUMENTA (13) is notable for its increased use of “non-traditional” exhibition spaces, many of which can be found in the Karlsaue Park lands that extend from one of the site’s more lavish structures, the Orangerie. Some of the artworks, such as Omer Fast’s video loop Continuity (2012) (Stan Douglas meets Jeff Wall—with corruptions by Atom Egoyan), fit neatly into purpose-built wooden huts, while others are concerned with the land underfoot. Such is the case with Gareth Moore’s A place—near the buried canal (2010–12), where the structures are designed and executed not by dOCUMENTA (13) architects and carpenters, but by the artist himself.

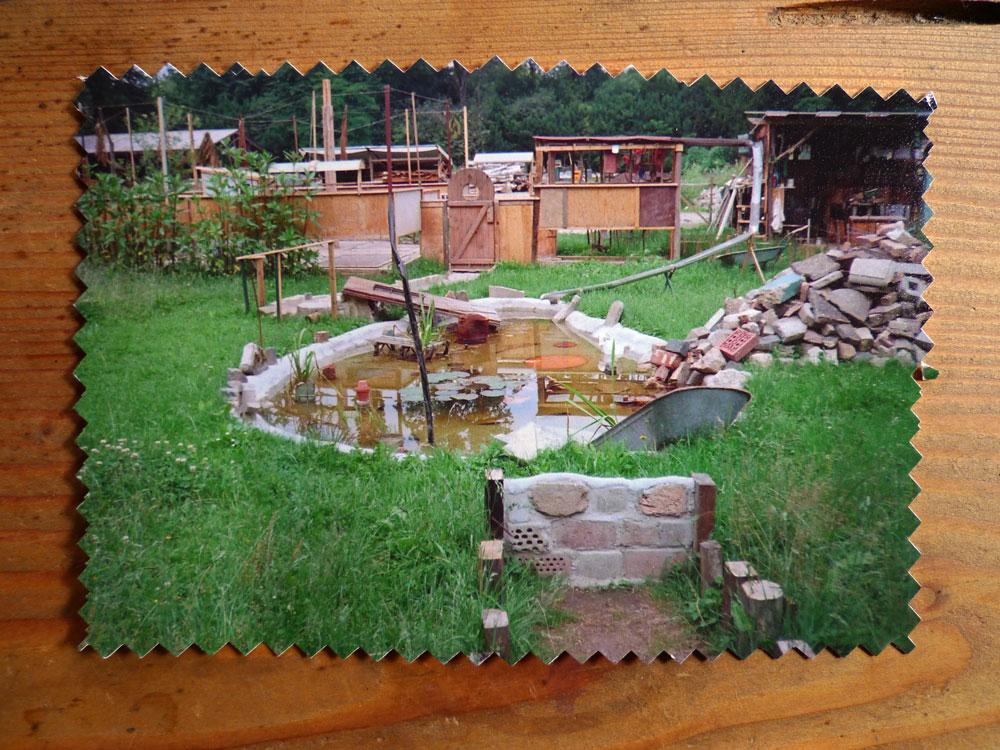

Since the spring of 2010, Moore has lived in a field beside the Karlsaue’s maintenance yard, erecting first a shelter, then a tool shed, a 12-foot-by-8-foot domicile (complete with stone chimney), a smaller “pension” for guests, a cairn-style washstand, a merchandise kiosk/meditation centre, a “basketball court,” a daybed platform, an adjacent “footbath” (with water lilies), a circuit of pathways and, finally, an entrance booth through which visitors pass en route to touring the grounds. Most of the materials used in this sculptural idyll are locally sourced—leftover wood from the previous documenta, but also windows from the recently renovated Brothers Grimm Museum. A statue of Vulcan, the Roman god of fire, was requisitioned by Moore from the exhibition’s main building, the Fridericianum, and enshrined where the field meets the trees.

As with his previous installations—from his and Jacob Gleeson’s St. George Marsh (2005–6), a corner store emporium in a residential neighbourhood in East Vancouver, to his immersive exhibition “Selected Chapters from Uncertain Pilgrimage” (2009) at Catriona Jeffries (the result of his global travels)—Moore proves himself adept at taking ostensibly disparate objects and combining them through a form of montage assembly into new objects that evoke intriguing (but never binary) relationships. Utility and fragility, harmony and injury, representation and transformation are all in abundance at A place.

Indeed, everywhere you look there is evidence of the artist’s hand, often to meticulous and surreptitious ends. For example, on the back stoop of the “pension” (where I slept two nights in early July) I noticed that the lantern hanging from the roof’s soffit did not begin its life as a lantern, but as a gas can. Looking closer, I saw that the lantern’s interior does not contain a wick or provision for oil, but a pane of red glass through which the installation’s entrance booth can be pictured, almost like a fly in amber. After viewing the booth in this light, I returned to its site’s wooded and ever-narrowing approach, accosted by what seemed like an inordinate amount of signage (an explanation of what I will find inside, prohibitions concerning cameras and cellphones, no dogs, no public toilet, an invitation to “VISIT VULCAN”… ).

While the approach and the signage had an unsettling effect on me, those ahead (mostly German and US seniors) read aloud these signs with great delight, as if what they were about to enter was not an ambiguous environment indifferent to their presence but something certain, in the same way a botanical garden or a graveyard could be imagined in advance of our visits there. However, this altered somewhat when we came to the booth, where an officious young art student/volunteer asked for our telephones and cameras (postcards, we were told, could be purchased at the kiosk). One patron gleefully handed over her bag, announcing that her camera was inside, only to be told that the camera must be removed, that the storage cubbyholes (designed by Moore) are not for bags but for phones and cameras only. For some, the spell was broken. For others, such as myself, a new lens appeared through which to view Moore’s fantastic installation.

Moore’s rules regarding the seizure and compartmentalization of our cameras and telephones, like the narrowing of the entranceway, foreshadow what lies ahead: a circuit of roped paths that lead to structures one is invited to touch (the daybed, the foot pond, the kiosk/meditation centre, the shrine to Vulcan) and those one can only pass by (the outhouse, Moore’s home, the “pension”). When asked about this strategy, Moore said it was not until opening day that he realized viewers would stray from his paths and trample the crabgrass and clover that distinguishes them. Rather than see his gardens flattened, the installation reduced to a muddy expanse, he installed fences, a move that protects the flora but also re-inscribes a singular regime through which the structures can be experienced—in the same way a novel is expected to be read from start to finish through a series of numerically ordered chapters.

The literary analogy is not inappropriate, for Moore has, over the years, proven to be as much influenced by literature (Lord Baden-Powell’s militaristic Scouting for Boys and T.E. Lawrence‘s translation of The Odyssey are two of the five books to be found inside the “pension”) as the visual arts (Noah Purifoy, Kurt Schwitters and Maud Lewis are cited in reference to Moore in the dOCUMENTA (13) guide). Yet while literature remains as open to lyrical abstraction as the visual arts are to narrative figuration, the unexpected contingencies of audience have backed A place into something resembling the latter: a closed structure, as opposed to a rhizome sustained by myriad assemblages within. I offer this (Deleuzian) observation to Vulcan and am reminded of his own open-ended tendency: as a smith, he is responsible for two kinds of fire—that which helps and that which hinders.