Time is an abstraction—just a meaning

that we impose upon motion.

So writes Anne Carson in her epic poem, Autobiography of Red, a text that is as much about photographs, strangely enough, as it is a coming-of-age story based on an ancient Greek myth. It is a phrase that came to mind repeatedly as I wandered through Fiona Annis’s latest solo exhibition, “The stars are dead but their light lives on,” a multi-sensory installation that combines sculpture, text, sound and light to record the traces left behind by dying stars. It was an ambitious, complicated exhibition that tackled heady themes of time, infinity and entropy, sometimes threatening to lose track of the viewer in its metaphysical musings. But, like good poetry, you can also lose yourself in Annis’s installation, immersed in its rhythms, which seem to echo like incantations from the distant past.

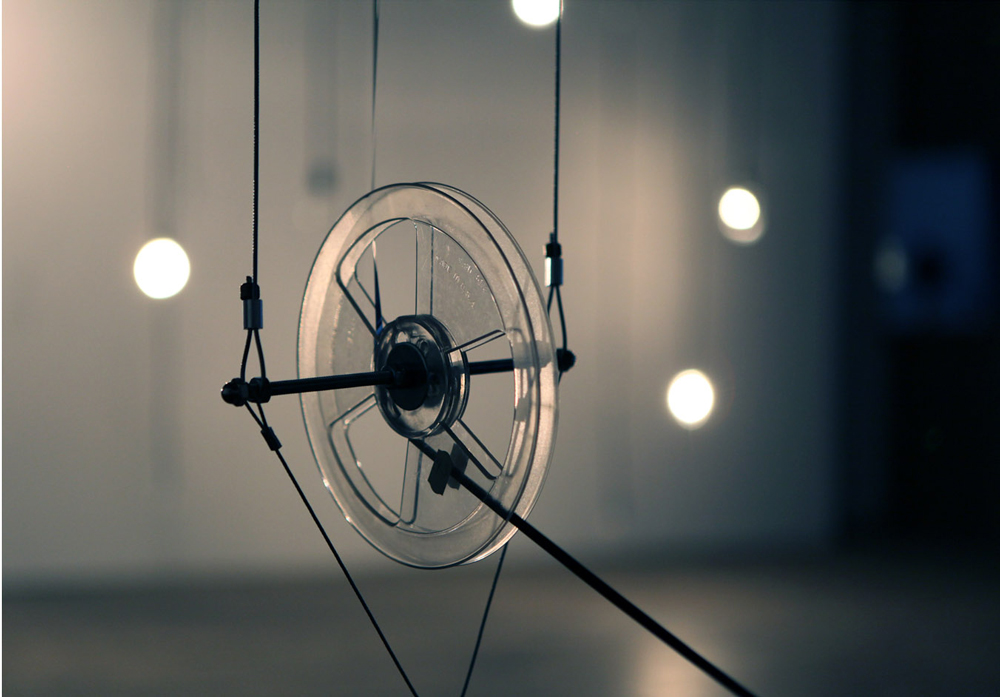

Though Gallery 44 is a venue devoted to photography, Annis’s work is more about the idea of photography than photographs themselves, meditating on two qualities the medium is uniquely capable of registering: light and time. Or, to be more exact (given her obsession with astronomy in this work), the way that light travels through time to reach us in the present. At the centre of the exhibition was Untitled Symphony (SN 1987A) (2014), an installation of nearly 100 light bulbs dangling from the floor to the ceiling that illuminate intermittently. Though the bulbs emit a soft, gentle glow, their light reflects a much more powerful and violent event: the project translates data collected by the Hubble Telescope that tracks the movement of matter released by a supernova whose light only reached earth in 1987 and has formed an unusual infinity symbol in the particulate matter left in its wake. As the lights turn on and off, we are watching the afterimages of faraway stars as they are born and die. Amid the flickering lights, a sound installation, There is music in the spacing of the spheres (2013), tracks another cosmic event, this time the reverberations of matter initiated by the Big Bang. Three reel-to-reel tape machines positioned on each side of the gallery play huge loops of tape that have recorded sonic interpretations of another set of dying stars, the ones that were born when the universe began. White noise, punctuated with low pulsating beats, combine with the whirring sounds of the tape players to produce a sound that is both entrancing and mildly discomforting. The composition will alter over the course of the exhibition, as the magnetic audiotape slowly erodes after weeks of continuous play, reflecting the ephemerality of matter as it travels through time.

In a second room, Annis’s work became more explicitly photographic, presenting a reproduction of a photographic plate from a 1910 observatory archive: a circular form that at first appears to be the moon, but is in fact an image of Halley’s Comet as it passed earth that year. Viewers then illuminate Star-Machine (Halley’s Passing) (2014) by cranking a primitive light box (repurposed from a 1930s telephone magneto), casting an eerie and flickering light on the celestial image. Nearby, six text panels reproduce sentences taken from Jeanette Winterson’s novel, Gut Symmetries, a love story between a physicist, his wife and his mistress (who, in true Winterson style, later becomes the wife’s mistress as well) that also ruminates on the notion of a Grand Unified Theory (or GUT), where separate forces are thought to merge into one at high energies. “You breathe time and time’s decay,” one of them reads. “Matter still imprinted with its echo.” Etched into anodized aluminum plates, the texts seem three-dimensional, projecting outwards from their black backgrounds like stars themselves. But their glossy surface also reflects the viewer’s image back at them, adding a kind of photographic imprint onto the work’s mode of display.

In this backroom, the viewer can find herself again in an exhibition that was sometimes overwhelming in its array of references and sensory experiences. When an earlier version of the installation was first presented at Montreal’s Eastern Bloc, at a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it two-day exhibition that served as the culmination of Annis’s 2013 residency there, the light bulbs were strung across the entire room, presenting a field of pulsating lights that could be observed from a fixed point. At Gallery 44, however, the lights were clustered into nine groupings around the gallery, stretching web-like from boxes suspended from the ceiling. This new spatial arrangement had the unsettling effect of shifting the spectator’s position, from that of the astronomer, firmly anchored on the ground, to the astronaut, floating amongst the constellations. I wondered what this unmoored position might have to say about photography’s position in the present moment. Like so many projects that have returned to antiquated technologies in the face of digital ubiquity, Annis’s installation works to fetishize older forms of analog photography, audio recording and projection: to make us wish we could slow down or stop time, and the degradation and loss it inevitably brings with it.

Perhaps that is fitting for a show that also takes death as one of its central themes. As the title makes clear, the stars we are seeing and hearing died long ago, their light just arriving to us now. Much like Annis’s previous series, which saw the artist document the locations where intellectuals, novelists and other artists had produced their final works shortly before their untimely deaths, here photography and death are intimately intertwined. If photography freezes time, freezes motion, it does so temporarily. As Annis’s installation demonstrates, time—like light—will continue on without us.