Wind spirals over the Mojave Desert. The mountains in the distance look like the backdrop of a vast, lifeless stage set. A toy soldier crawls commando-style down a paved highway. A cargo train rolls by.

These are the beautiful, sinister opening shots of Emanuel Licha’s two-channel video Mirages (2010), part of his late-spring Montreal exhibition “Why Photogenic?” Cut and we enter Fort Irwin, a U.S. military training centre that contains a replica of a typical Iraqi town. Thanks to a team of Hollywood experts and army engineers, not only buildings and roadways have been replicated but so have, allegedly, the fear and chaos of war. Two thousand people inhabit this “box,” as the army calls it, playing “culturally correct” roles: amputees (reminiscent of Jeff Wall’s Dead Troops Talk) and otherwise wounded soldiers receive practice fi rst aid, a bleating goat is pulled along by a line around its neck, cars explode randomly, snipers in ghutras are hunted down, laundry hangs to dry and the muezzin calls for prayer—all within a fi ction that extends for 1,000 square miles.

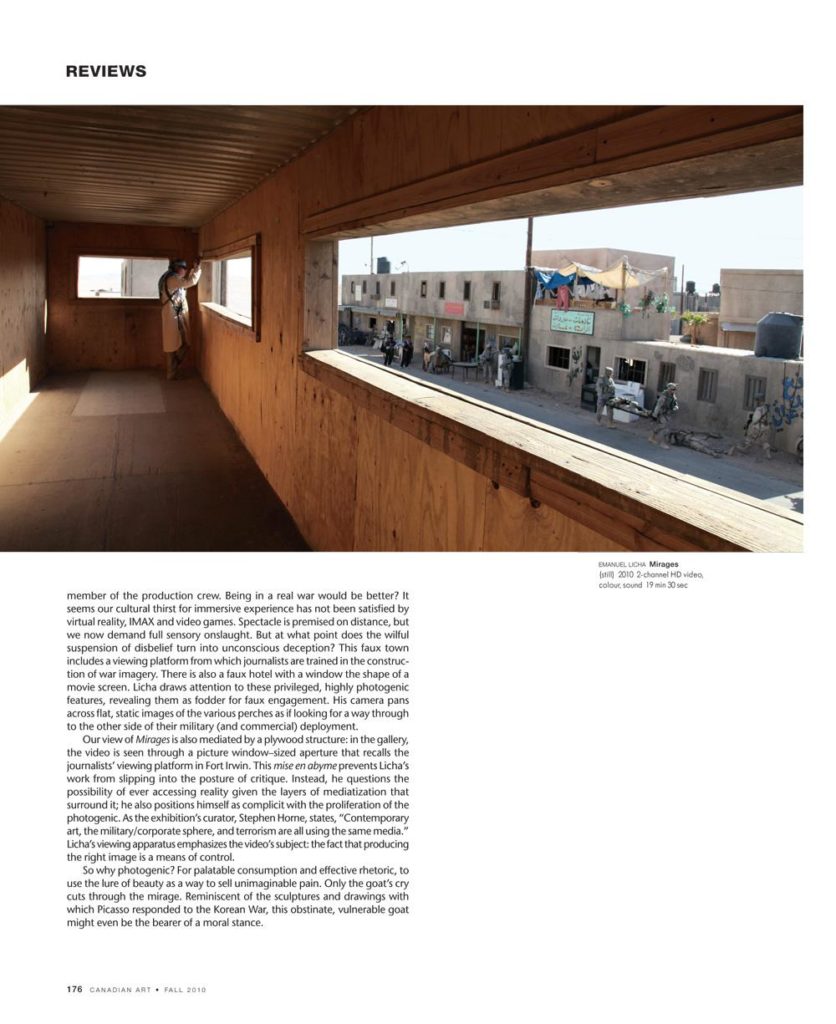

“It can’t be better than the real thing, but it’s very close,” states one member of the production crew. Being in a real war would be better? It seems our cultural thirst for immersive experience has not been satisfi ed by virtual reality, IMAX and video games. Spectacle is premised on distance, but we now demand full sensory onslaught. But at what point does the wilful suspension of disbelief turn into unconscious deception? This faux town includes a viewing platform from which journalists are trained in the construction of war imagery. There is also a faux hotel with a window the shape of a movie screen. Licha draws attention to these privileged, highly photogenic features, revealing them as fodder for faux engagement. His camera pans across fl at, static images of the various perches as if looking for a way through to the other side of their military (and commercial) deployment.

Our view of Mirages is also mediated by a plywood structure: in the gallery, the video is seen through a picture window–sized aperture that recalls the journalists’ viewing platform in Fort Irwin. This mise en abyme prevents Licha’s work from slipping into the posture of critique. Instead, he questions the possibility of ever accessing reality given the layers of mediatization that surround it; he also positions himself as complicit with the proliferation of the photogenic. As the exhibition’s curator, Stephen Horne, states, “Contemporary art, the military/corporate sphere, and terrorism are all using the same media.” Licha’s viewing apparatus emphasizes the video’s subject: the fact that producing the right image is a means of control.

So why photogenic? For palatable consumption and effective rhetoric, to use the lure of beauty as a way to sell unimaginable pain. Only the goat’s cry cuts through the mirage. Reminiscent of the sculptures and drawings with which Picasso responded to the Korean War, this obstinate, vulnerable goat might even be the bearer of a moral stance.

This is an article from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.