Divya Mehra’s title for her latest exhibition, “You have to tell Them, I’m not a Racist.,” comes from an interaction she had with a white person who, after saying something obviously racist, insisted that she salvage his reputation. That pressure to play on the whites’ team is the driving force behind this provocative and tongue-in-cheek exhibition, an earlier version of which was presented at La Maison des artistes visuels francophones in St. Boniface in 2012.

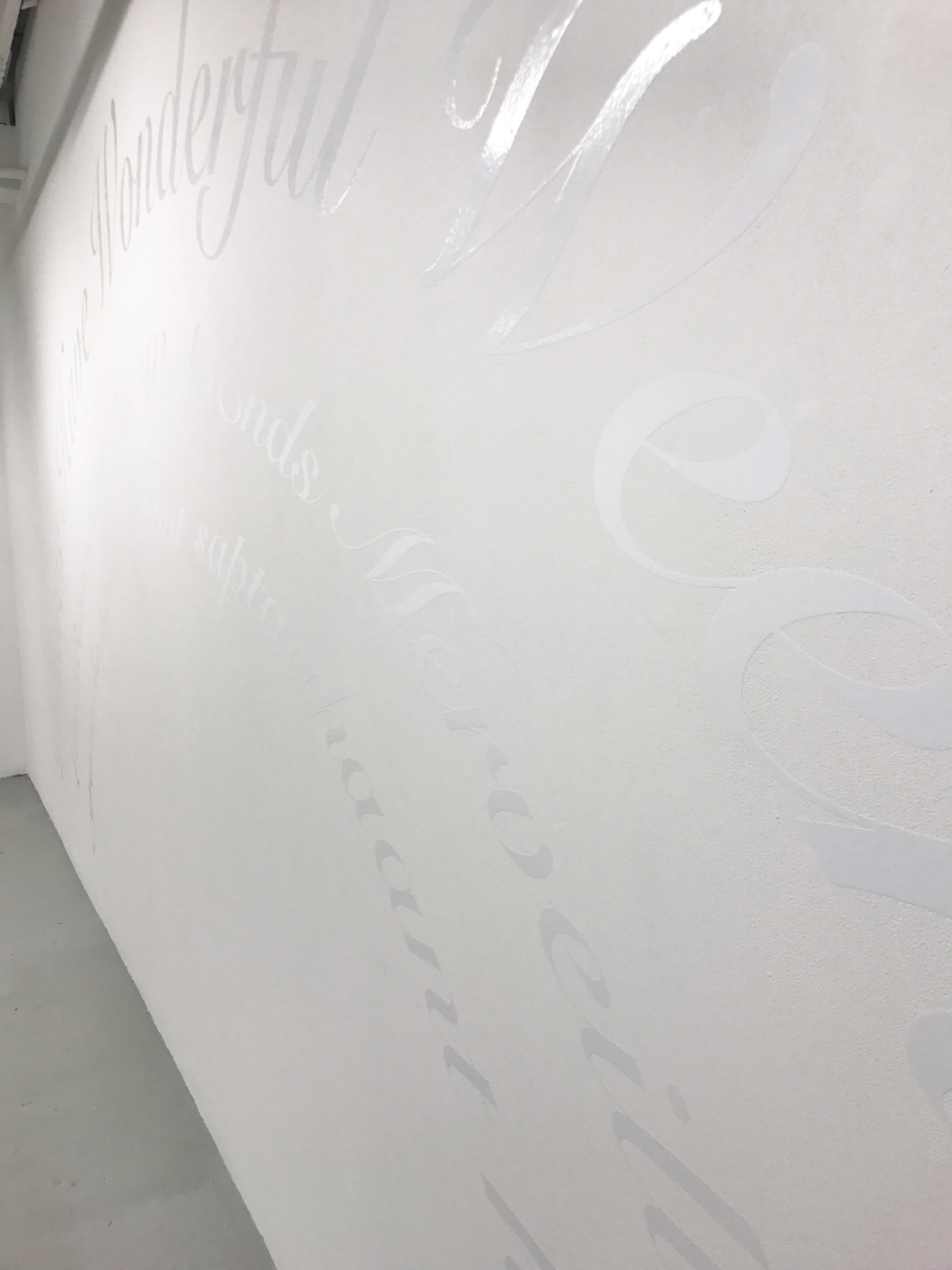

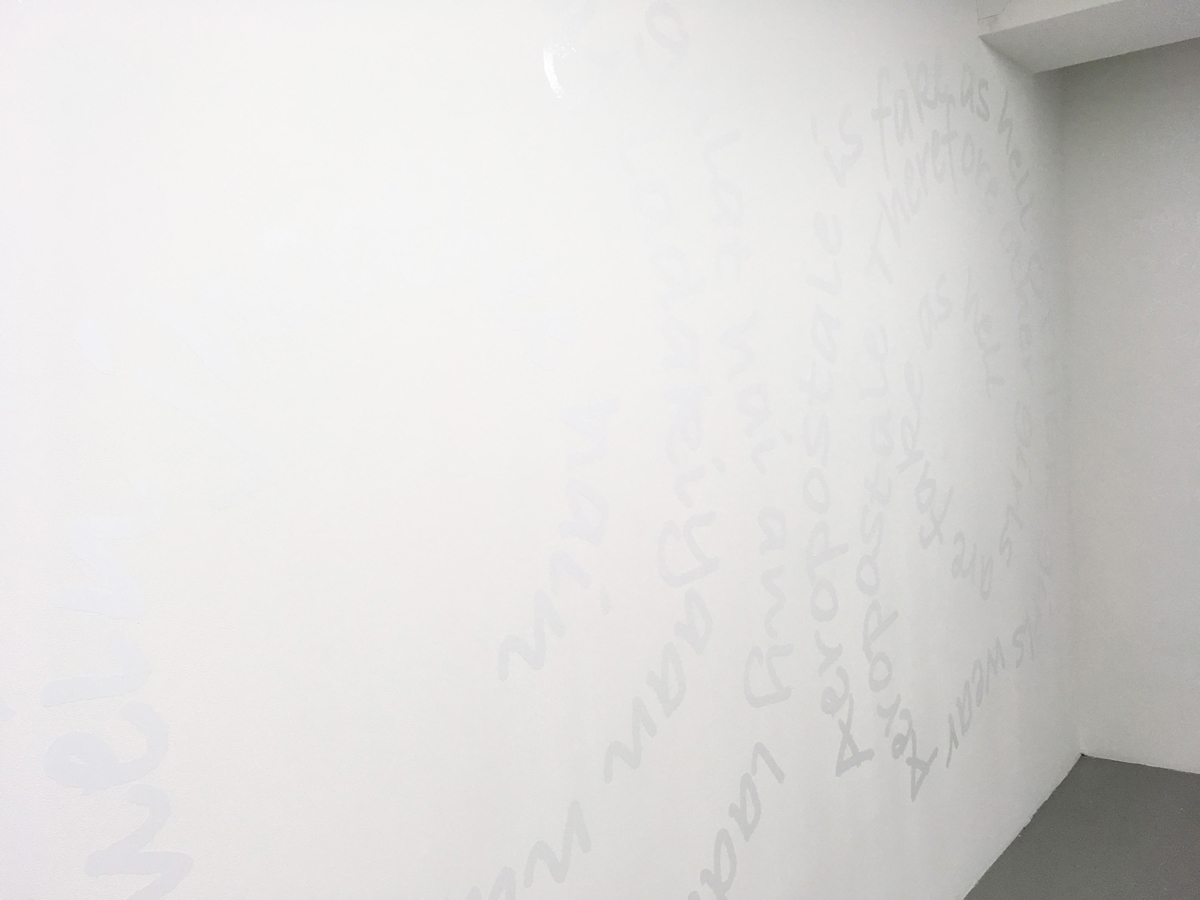

Mehra’s use of white acrylic-vinyl texts on white walls resists easy consumption by straining the eye, forcing the viewer to experience a prolonged, conscious discomfort. Under the harsh glare of white lights, one finds no pleasure in the white cube here—the white-on-white colour scheme being perhaps a nod to our institutional and canonical overlords, not to mention the contemporary obsession with minimalism. But Mehra thrives in this perverse environment, poking at dull assumptions of what “race” art might look like. She’s complicit in it, unafraid of being a sell-out (what does that term even mean?) and, frankly, does not give a fuck.

Of course, that’s not to say we’re not talking about race—the translations of some text pieces, bounced between English, French and Hindi through Google Translate to distort their meaning, are charged with longing and lostness, feelings familiar to any diasporic subject. For a deadbeat child like myself who didn’t learn my parents’ languages, Google Translate is a necessary interface that mediates my relationship to a culture to which I have a claim, but which may ultimately be beyond my understanding. Google Translate’s two-box interface impossibly visualizes a relationship between different languages (that is, systems of meaning) where x = y = z, soothing the burn that is losing a part of ourselves in translation.

One of the wall texts in Divya Mehra’s exhibition reads “Whites Have Wonderful Weekends.” Photo: Georgia Scherman Projects.

One of the wall texts in Divya Mehra’s exhibition reads “Whites Have Wonderful Weekends.” Photo: Georgia Scherman Projects.

The first text piece in the show is a quote from Nikki Samuel, the white woman who demanded a white doctor at a Mississauga clinic in June; it is a wild instance of racism but, of course, not an uncommon one. None of the casual racism in the exhibition from strangers, colleagues and lovers should be remarkable to anyone with darker skin—somehow, the mere fact of racism still manages to surprise while also being an exhausting reminder. Certainly the effect was exhausting on my eyes, straining as they were to read the white acrylic type.

Another text, “Whites Have Wonderful Weekends,” arcs across a wall in cheesy, ornate script. It’s based on a Steve Harvey joke about how white people plan activities for their weekend, while Black people merely have days off, exhausted from the work week (and presumably, systematic racism). The joke is about white people, yet the punchline is Black people. The false virtue of using laughter as a coping mechanism is often attributed to racialized people as a sign of resilience, while the reasons behind that person’s suffering go unaddressed. In the title of this piece, How you gonna hate from outside The Club (Direct Realism), Mehra layers an additional criticism that undermines those weekend activities. White people distinguish their whiteness against racial Otherness, but only insofar as it doesn’t threaten their social capital.

Within the defaced white cube, it’s clear that Mehra draws on traditional theories of presentation, with lighting and sight lines arranged just so. Working within the lexicon of capital-A Art, one can’t help but notice that the white cube often fails to accommodate art about racialized identities without fetishizing or appropriating their power, forcing artists to play by their rules in order to gain legitimacy (often in its cheaper incarnation, visibility). Enlarging these cynical-comical instances of casual and institutional racism to art-sized proportions somehow reinforces their near-invisibility; perhaps to a white audience, the sensation is akin to having a shit pie thrown in your face.

Another of the white-on-white wall texts in Divya Mehra’s exhibition “You have to tell Them, i’m not a Racist.” Photo: Georgia Scherman Projects.

Another of the white-on-white wall texts in Divya Mehra’s exhibition “You have to tell Them, i’m not a Racist.” Photo: Georgia Scherman Projects.

There’s pleasure to be taken in getting back at your haters, sure, but it’s the sincere question posed by Currently Fashionable, a wall-sized decal simply saying “PEOPLE OF COLOR,” that’s the most intriguing part of the exhibition. Mehra’s titling suggests that the phrase is as ephemeral as the intersectional politics that brought the term to the forefront of social justice rhetoric. As Mehra’s Google-Translated wall texts demonstrate, language is porous, malleable and organic. Language, much like a human body and nature, eventually decays. The term Mehra applies here in block letters, a term sometimes used to imply solidarity amongst non-whites, does little to address the intra-racial politics that are more complicated than simply being articulated against whiteness—much less the anti-Blackness that continues to exist in non-white communities.

It makes the situation seem almost ironic. What used to be a source of indignance—“colored” being, historically, a pejorative—is now supposed to be a source of collective power. How did we get conned into willingly calling ourselves colored? The linguistic conflict exposes a limit of intersectional language: that the words we’re using to describe ourselves are hardly adequate enough to do that. Currently Fashionable not only takes issue with meanings that have fallen out of favour, but asks what we’re left with in the end. It comes closer to articulating the as-of-yet unarticulated wheel-spinning sensation that left-leaning social justice politics seems to generate in those who have most strongly believed in those politics.

But that’s another discussion, for another time. Racialized people are tired of explaining the fact of racism. To that effect, Mehra doesn’t have to say anything at all—the writing’s on the wall.

Vidal Wu was Canadian Art’s 2017 editorial resident. His talk, “POC be like POC be like but they be the POC that be like” on Divya Mehra’s exhibition begins September 23 at 2:30 p.m. at Georgia Scherman Projects as part of Canadian Art’s Gallery Day. He tweets @vidalwuu.

Divya Mehra, Currently Fashionable, 2012/2017. Acrylic vinyl and latex deep base paint, dimensions variable. Photo: Via Georgia Scherman Projects Facebook Page.

Divya Mehra, Currently Fashionable, 2012/2017. Acrylic vinyl and latex deep base paint, dimensions variable. Photo: Via Georgia Scherman Projects Facebook Page.