Exhibition view of Claire Greenshaw’s “Mother Tongue” at Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Exhibition view of Claire Greenshaw’s “Mother Tongue” at Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

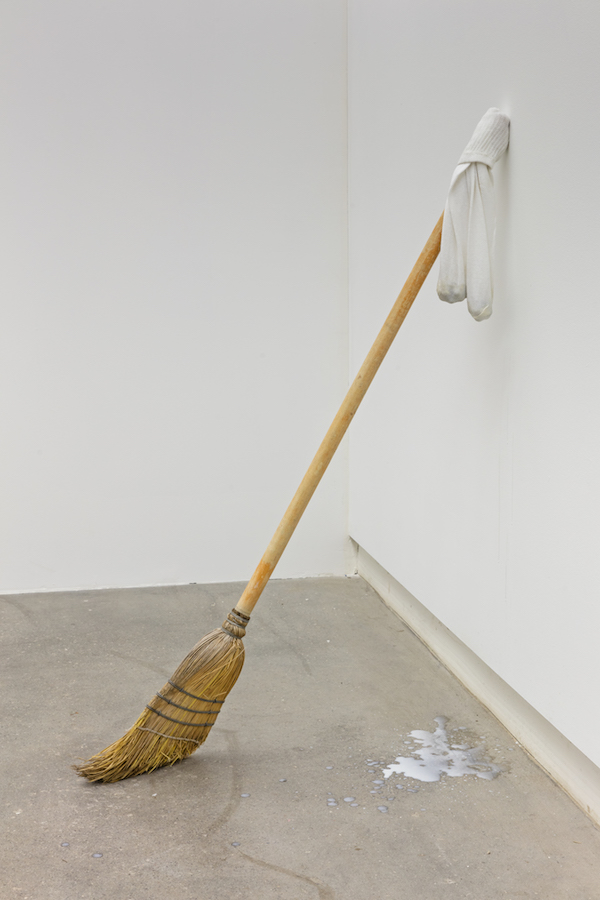

“Watch out for the milk,” Claire Greenshaw warned me, as I noticed a pale-yellow, filmy puddle of half-curdled substance pooled on the concrete floor. It had dribbled down from a pair of white tube socks, the kind a teenage skateboarder might pull halfway up his shins, except that these were balled up, droopy from being stuffed with marbles, and propped against the wall by a broom—altogether, elements constituting a sculpture.

Greenshaw was walking me through her exhibition “Mother Tongue” at Clint Roenisch in Toronto, a few hours before its public opening. When I’d first walked into the gallery and glanced the broom leaning against the wall, I’d wondered if it was there for my sake.

“It’s not breast milk,” she told me, smiling in a way that made me think it might be.

Claire Greenshaw, MILF, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, MILF, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

There are many repulsive words for mother—even an entire category of jokes about yo’ mama in particular—but the most insulting of them all might be MILF. Greenshaw’s MILF is a juvenile joke made material, laden with double entendres. The broom is two things at once: an exhausted prop of domesticity supporting socks sagging low from the weight of milk and marbles, but also a rigidly erect, phallic rod, from whose upright end piddles a milky, spunky emission.

Greenshaw initially balked at calling the show “Mother Tongue.” She’s a mother herself, of three little boys, but didn’t want to encourage readings of her work based solely on that fact. She’s a mother all the time, so of course she’s a mother at the same time as being an artist, but this status of occupying motherhood does not preclude her work from being about more than that. She admits that there’s also the nagging feeling that motherhood isn’t that welcome in the gallery setting, and wonders why that is.

The kind of mother she’s referring to here, then, is more the universal mother: the mother of language, the mother of the body, of origins themselves. “Either you are a mother or you have one,” said Greenshaw. “There’s no other way, scientifically thus far, that you could have arrived here.”

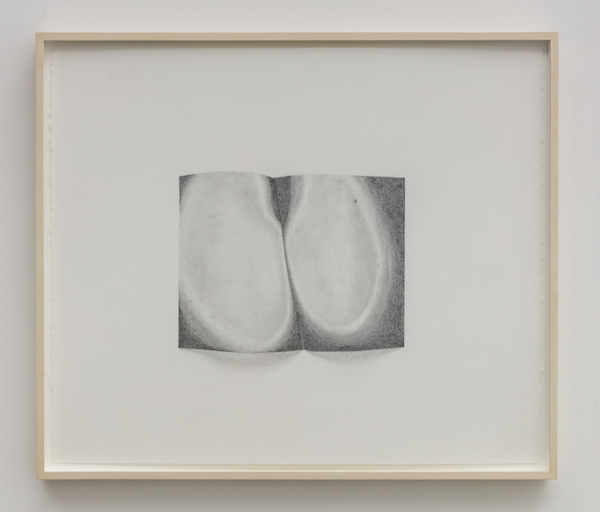

Claire Greenshaw, Research, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, Research, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Across from MILF is Research, a graphite drawing on paper that reveals itself to be, once you’ve figured out what you’re looking at, Greenshaw’s version of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde. It’s a faithful representation of a bum sitting on a photocopier—a copy of a copy—with pubes sprouting from where she’s drawn the paper’s crease.

There’s no escaping the body in this exhibition—or otherwise, of course. Greenshaw told me that she was interested in investigating how the very act of making images serves as a constant reminder of embodiment, and of how little our bodies have actually changed throughout human history, despite all of the technologies that we have invented.

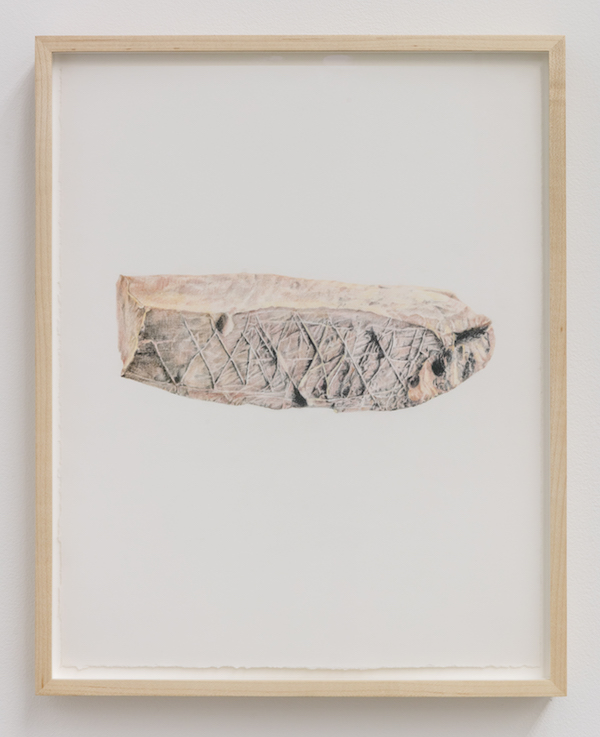

Claire Greenshaw, 75,000 Years of XXX, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, 75,000 Years of XXX, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

75,000 Years of XXX is a drawing of a photograph Greenshaw found in an old copy of National Geographic of a chunk of crosshatched ochre discovered in South Africa’s Blombos Cave. Anthropologists say that these incised implements represent the earliest forms of symbolic representation. In excavations of sites like this, apparently, it is not uncommon to find ochre deposits up to eight inches deep. The iron-rich mineral pigment was used to create drawings, and was used to colour body parts, too.

Ochre might even be a key to understanding how language developed. One controversial (yet highly normative) theory of evolutionary linguistics says that early Homo sapiens females applied ochre to themselves in a cosmetic fashion to mimic menstruation, as a way of consciously controlling the signals of menstrual synchrony—what is now called the McClintock effect. By doing so, they could ensure that they would each be guarded by a male consort, and could resist the strategy of a dominant male seeking to establish a harem. From this social ritual of kinship, this theory posits, cognition developed, followed by language. Eons later, “XXX” still designates sexuality, both illicit and affectionate.

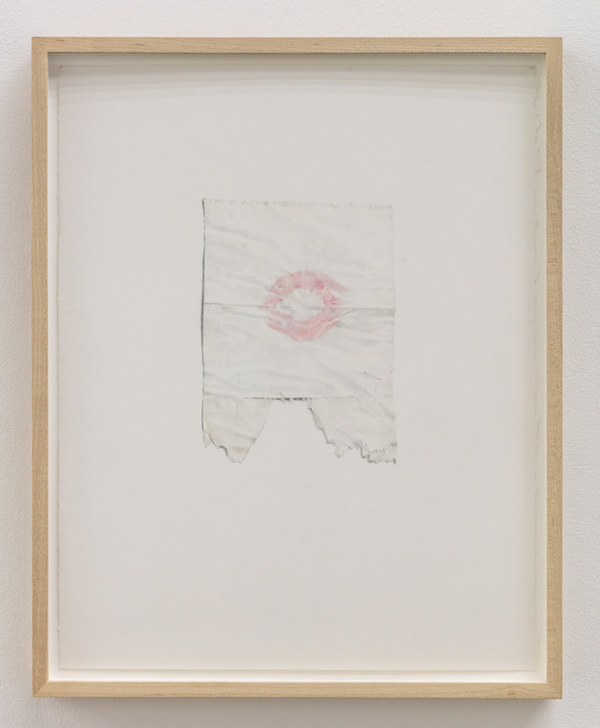

Claire Greenshaw, Scold’s Bridle, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, Scold’s Bridle, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Tucked in a corner is the imprint of a kiss. Scold’s Bridle is a drawing of a torn square of toilet paper that’s been used to blot freshly applied red lipstick, the kiss mark arranged in the shape of the first syllable of Joyce Wieland’s O Canada (1970). It’s a tiny freak flag, an embracing of feminine power and sexuality, while also a memento of that quiet final moment you have with yourself during the getting-ready ritual before joining the party’s throng.

But then the work’s title lends a discomfiting layer of meaning. In England and Scotland during the Middle Ages, nagging, gossiping or outspoken women—often feared to be witches—were punished by being forced to wear the scold’s bridle, an iron face-cage. When padlocked shut around her jaw, the bridle’s spiky bit projected into the woman’s mouth, holding her vicious tongue in place, and making it too painful for her to speak. Pain’s an effective method of punishment, but to really silence a woman, longer-lasting results are achieved through humiliation.

Claire Greenshaw, ;’), 2017. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, ;’), 2017. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

“It’s funny, isn’t it? The abject follows us like a shadow,” Greenshaw said. “It’s indispensible. We leave traces even when we don’t mean to.” Thinking about this, and about the body as a tool, Greenshaw looked to her iPhone screen to create a large charcoal drawing that magnifies the grease-smudges her fingertips make on its surface. The enlarged smudges she’s drawn coalesce to form a smiley face, or a vanitas-painting skull.

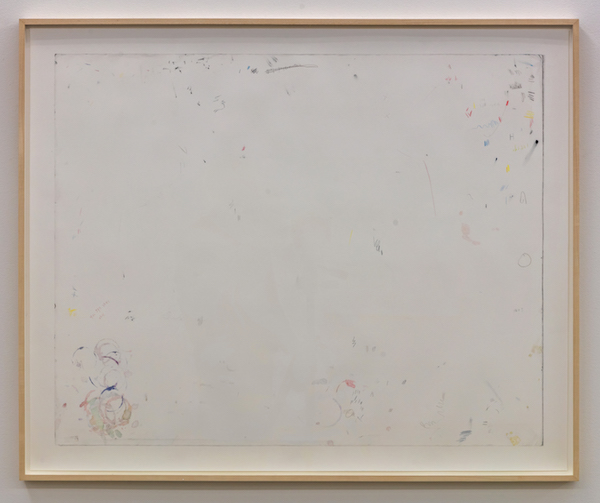

Claire Greenshaw, Supportive Nonentity, 2017. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, Supportive Nonentity, 2017. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In Supportive Nonentity—character traits sometimes used to describe a perfect wife—Greenshaw’s made a faithful duplicate of her studio matboard, replete with splashy rings leftover from cups of coloured water, coloured-pencil scribbles and traces of unattributed phone numbers. It looks a bit like a Cy Twombly pushed to its edges. Across the room, like a mirror, Marked magnifies a small section of it, isolating the composition of just the watery circles.

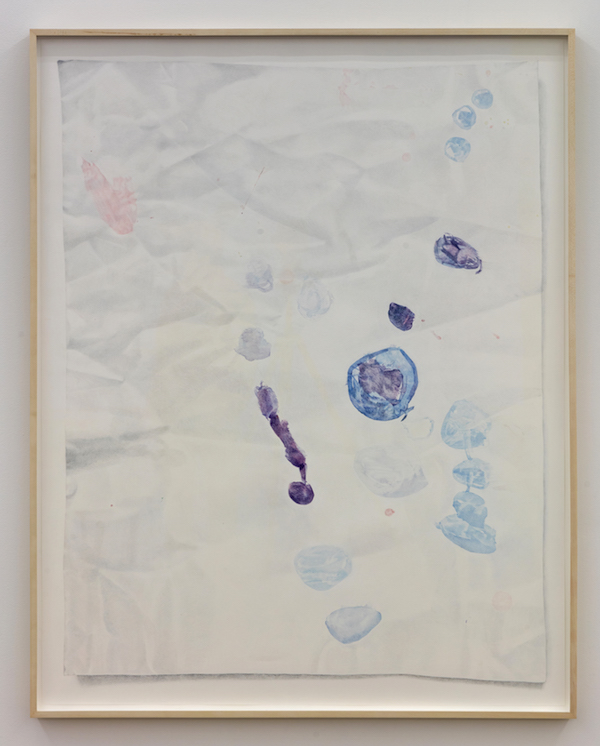

Claire Greenshaw, Zeuxis Can Eat Me, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, Zeuxis Can Eat Me, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Greenshaw says that drawing things is the best way of understanding them. When her eldest son was about four years old, Greenshaw asked him to draw her some grapes. Using his paint set, he put down a few light bluish-purple dabs on the page. She enlarged these splodges and dutifully reproduced them to create Zeuxis Can Eat Me, whose title references the story of Ancient Greek painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius. The two best artists of fourth-century BCE Greece entered into a competition to see who could create the most realistic painting. After Zeuxis painted grapes so lifelike that birds tried to peck at them, he asked Parrhasius to lift the curtain he’d covered his painting with—before realizing that the curtain itself was, in fact, the painting. Zeuxis quickly admitted defeat.

Claire Greenshaw, Nice Legs, What Time Do They Open?, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Claire Greenshaw, Nice Legs, What Time Do They Open?, 2016. Courtesy Clint Roenisch. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Holding court over the gallery is a pair of stockings, stretched over wire and held upright by plaster casts of liquor bottles. Nice Legs, What Time Do They Open? is the bastard child of Martin Kippenberger’s Alcohol Torture and Sarah Lucas’s Bunny Gets Snookered (Louise Bourgeois is its grandmother, and Vanessa Beecroft its estranged weird aunt). Its bawdy, bowlegged stance conveys drunken swagger, vulnerability to penetration and the position legs assume when they part to give birth. It seems to maintain a precarious balancing act.

“Some people are always thinking about their next show, and then when it comes time to make stuff, they just hole up and make everything at once, but that isn’t how it is for me,” Greenshaw admitted. “I am constantly chipping away, stealing moments of studio time when I can get them.”

Her process is laborious, methodical, somewhat painstaking. It gives her time to make mistakes, and to find the beauty in them. “I’m slow,” she told me. But when compared to the timeless gesture of drawing throughout human history, I would argue that she is keeping pace.