Andrew Owen’s basic idea is elusive. But then that’s exactly the core of Andrew Owen’s basic idea: that a great deal eludes us, perhaps nowhere more than in the consumerized West. We live, asserts Owen (who also goes by the name AO1)—via the impressive range of work that comprises his first solo show in Canada in almost 20 years—on the twilight side of a yawning subjectivity gap, a chasm of personal and cultural bias that separates us from the truth about…well, just about anything.

Art objects are crucially implicated in this analysis, of course, with the subjectivities of both the artist and the viewer contributing to a permanently flawed communication. How to conquer that? This is in effect what Owen asks. His answer: to get the artist out of the way to whatever degree possible. Each work in this show represents a discrete attempt on Owen’s part to do so.

I say “elusive” because the idea takes some teasing out. At first glance, the show incorporates work so varied in terms of media and aesthetic tone—from floral paintings to fragmented photographic collages to repurposed ad-covered hoardings—that it would be easy enough to conclude that three or four artists were involved. But it’s all Owen, and all in the same conceptual key. Once we sense this harmonization, the body of work transmutes satisfyingly from multifarious to cohesive.

The floral Impressions are field compositions, positive stencils made by building up successive layers of paint and wildflowers on the canvas. Traces of the plants and flowers used in the process remain, paint ghosts in under the leaves and the works have been subject to the whims of wind and other conditions in the field. The flowers have been allowed, in effect, to speak for themselves.

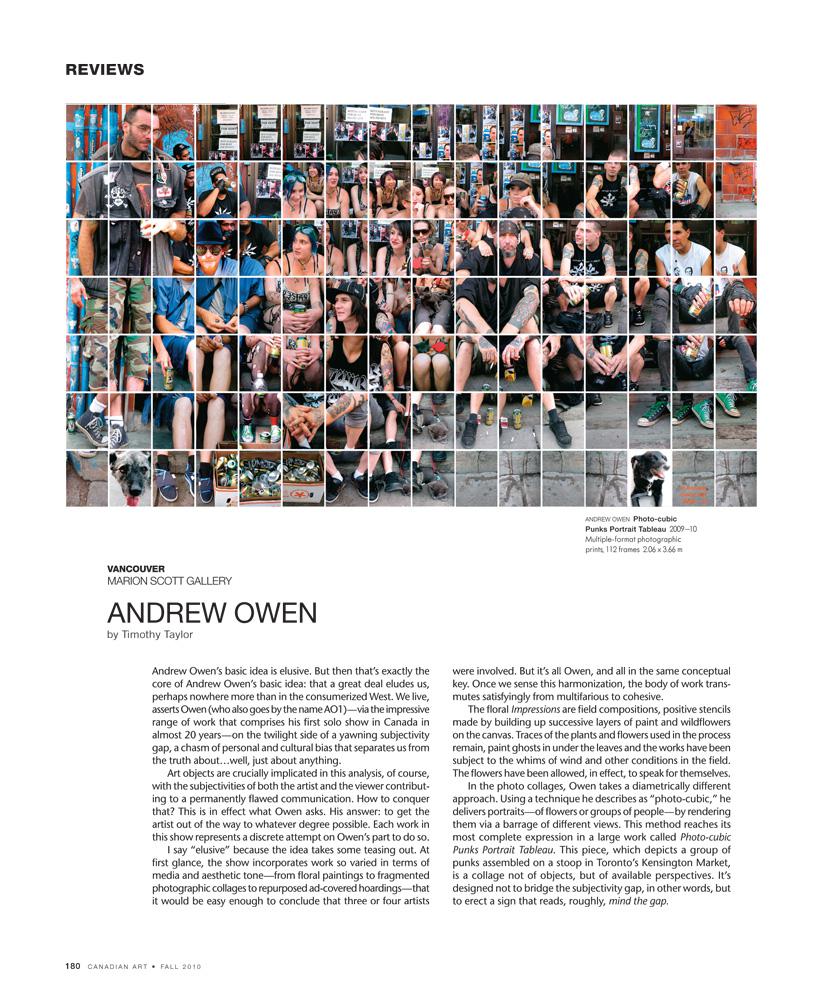

In the photo collages, Owen takes a diametrically different approach. Using a technique he describes as “photo-cubic,” he delivers portraits—of flowers or groups of people—by rendering them via a barrage of different views. This method reaches its most complete expression in a large work called Photo-cubic Punks Portrait Tableau. This piece, which depicts a group of punks assembled on a stoop in Toronto’s Kensington Market, is a collage not of objects, but of available perspectives. It’s designed not to bridge the subjectivity gap, in other words, but to erect a sign that reads, roughly, mind the gap.

This is an article from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Spread from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art

Spread from the Fall 2010 issue of Canadian Art