This is an article from the Winter 2016 issue of Canadian Art.

George E. Russell was at work in his studio when he received a game-changing phone call. “The ID said Arthritis Society, and I considered not picking up,” he admits. “I explained that I was working on a watercolour and had to finish a certain area before the paint dried.” Upon discovering that Russell was an artist, the caller, Quebec Arthritis Society director of development Elizabeth Kennell, asked if he would donate a work. Russell, now 82 and a retired high-school teacher, invited Kennell to his Laval home to survey his watercolours, acrylic-on-Masonite pieces and sculpture-painting hybrids.

Kennell was astonished by what she saw and even more staggered when Russell offered to donate the entire collection of more than 400 works. She called Yolande Racine, former contemporary-art curator at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, for a second opinion. Racine concurred that Russell was not just a generous donor but also an undiscovered serious talent.

Originally from rural Saskatchewan, Russell moved to the belle province in 1969, where he entered the master’s program in art education at Sir George Williams University. He had excelled at math in high school and was instinctively drawn to the Plasticiens, the postwar Quebec generation who favoured geometric precision over chaotic expressionism. But he never fully embraced their dogma. “Among contemporary artists in Laval,” says Russell, “my art was refused because I was working partly in watercolour,” a medium more associated with realism than hard-edge abstraction.

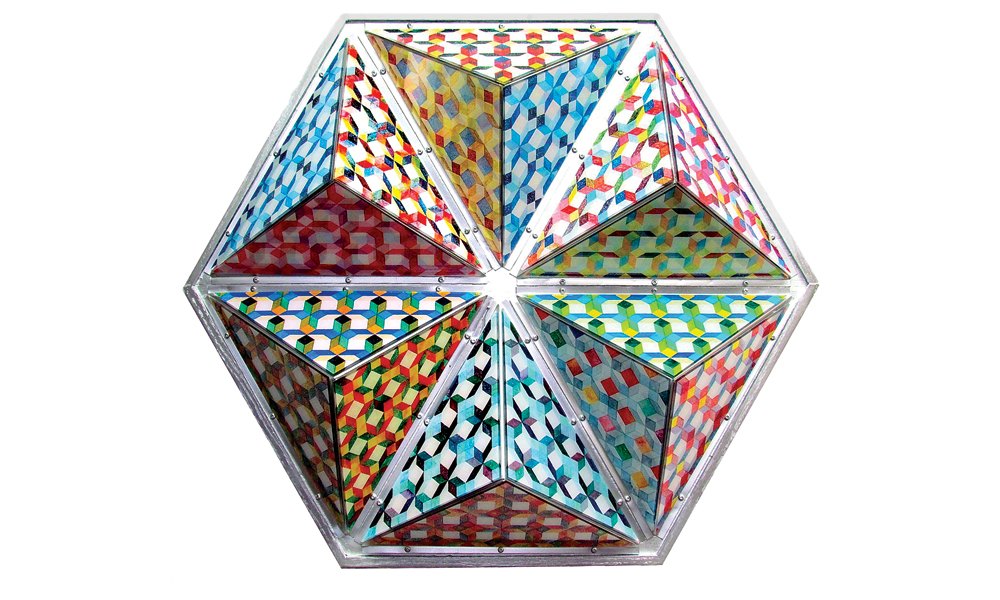

Many of Russell’s canvases are cut into an elongated hexagon, resembling the body of a UFO. He traces monochrome or multicoloured patterns in zigzags, stripes or trapezoids, creating dizzying optical illusions. In some paintings, the hues seem to dance like fireflies; in others they oscillate rapidly like a malfunctioning traffic light. His Kaleidoscope (2000–) series consists of three-dimensional multi-panel stars, some wider than five feet. You can rearrange the panels, which are attached to the central body with Velcro or magnets, or nail the structures to the wall and spin them like pinwheels.

Racine has a Russell painting in her dining room—a striped blue-and-white hexagon that seems to pull you in and repel you at the same time. There are two painted triangular boards on each end, affixed to the main rectangular body with hinges. When you turn these doors inwards, the painted lines seem to run together. Almost every dollar Racine spent on this unique piece will support arthritis research. She let me play with the triangular panels. The joints work perfectly.

George E. Russell,

Kaleidoscope A–Z Satellite, 2010–14.

George E. Russell,

Kaleidoscope A–Z Satellite, 2010–14.