Today, the Toronto Blue Jays play a baseball game that decides whether they will move through to the playoffs in the American League Championship Series, but there is more than just their season at stake. In this deciding round, they’re playing a team from Cleveland who use a racist slur and caricature as their name and mascot.

Yesterday, architect and activist Douglas Cardinal filed a legal complaint against the Cleveland team that asked the court to bar them from using their offensive name and mascot while in Ontario, pointing to this use as a direct violation of the Ontario Human Rights Code. Hours before Game 3, a judge dismissed the application. One of Cardinal’s lawyers told the New York Times that “Chief Wahoo,” the red-skinned caricature used as the team’s mascot, is “quite obviously a derogatory, cartoonish representation of an Indigenous person.”

The high-profile game is the latest event to have lent mainstream visibility to a debate that persists despite decades of protest: Why won’t major league sports abandon the use of offensive imagery and terminology, particularly when Indigenous peoples are the targeted group? Simply put, it’s racism. Searching the hashtag #NotYourMascot on Twitter will produce hundreds of reasons and examples of why Indigenous people reject forms of cultural appropriation that reduce fully formed human beings to simplistic, harmful stereotypes.

I recently wrote a report on how Canadian museums are treating the practice of renaming items in their collection that carry offensive, outdated terminology. When considering the issue of an offensive image being disseminated widely through a sports team’s logo, I wanted to reach out to visual practitioners who are attuned to the power of semiotic signifiers and especially sensitive to the indelible influence of visual information that is both directly and indirectly acquired.

There are sports commentators, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who simply refuse to say the full name of the Cleveland team. Sportsnet newscaster Jamie Campbell and others have followed the lead of Blue Jays broadcaster Jerry Howarth, who made a promise in 1992 to stop saying racist team names on air after receiving a letter from an Indigenous fan from Northern Ontario asking Howarth to consider the offensive associations that these words carry.

Cardinal’s recent complaint is not the first time Cleveland’s baseball team has faced legal trouble for their name and mascot. In 1972, the Cleveland American Indian Movement, who have protested at every home opener game for the team for more than 20 years, unsuccessfully sued Cleveland Baseball for libel and slander.

When Mark Shapiro, president and CEO of the Blue Jays, was president of the Cleveland team, he moved to relegate the Chief Wahoo mascot to secondary status, admitting that it personally bothered him. It was replaced by a block-letter “C” officially, but the caricature remains on the left sleeves of the team jerseys and on the baseball caps that have been worn by team members during post-season games. And fans still show up in redface and wearing headdresses, performing “tomahawk chops” and “war whoops.”

There are precedents in Canadian sports for teams changing their offensive names and mascots after receiving complaints, legal or less official, mostly below the major-league level (in the Canadian Football League, despite many calls to change their name, the Edmonton Eskimos have yet to take any action). In Ontario, Chinguacousy Secondary School in Peel changed their name from the Chiefs to the Timberwolves. In Saskatchewan, Balfour Collegiate in Regina is now known as the Bears, and Bedford Road Collegiate in Saskatoon goes by the Redhawks. Western Canada High School in Calgary, formerly known as the Redmen and now the Redhawks, spent $200,000 to get new uniforms and redecorate their gym. A Tribe Called Red’s Ian Campeau successfully campaigned for a youth football league in Ottawa called the Nepean Redskins to change their name to the Nepean Eagles in 2013.

Campeau and others, including American sports journalist Bomani Jones, have publicly worn a T-shirt that riffs on the Cleveland team’s branding, using a white-faced version of the Chief Wahoo logo under a swirling font that spells out “Caucasians.”

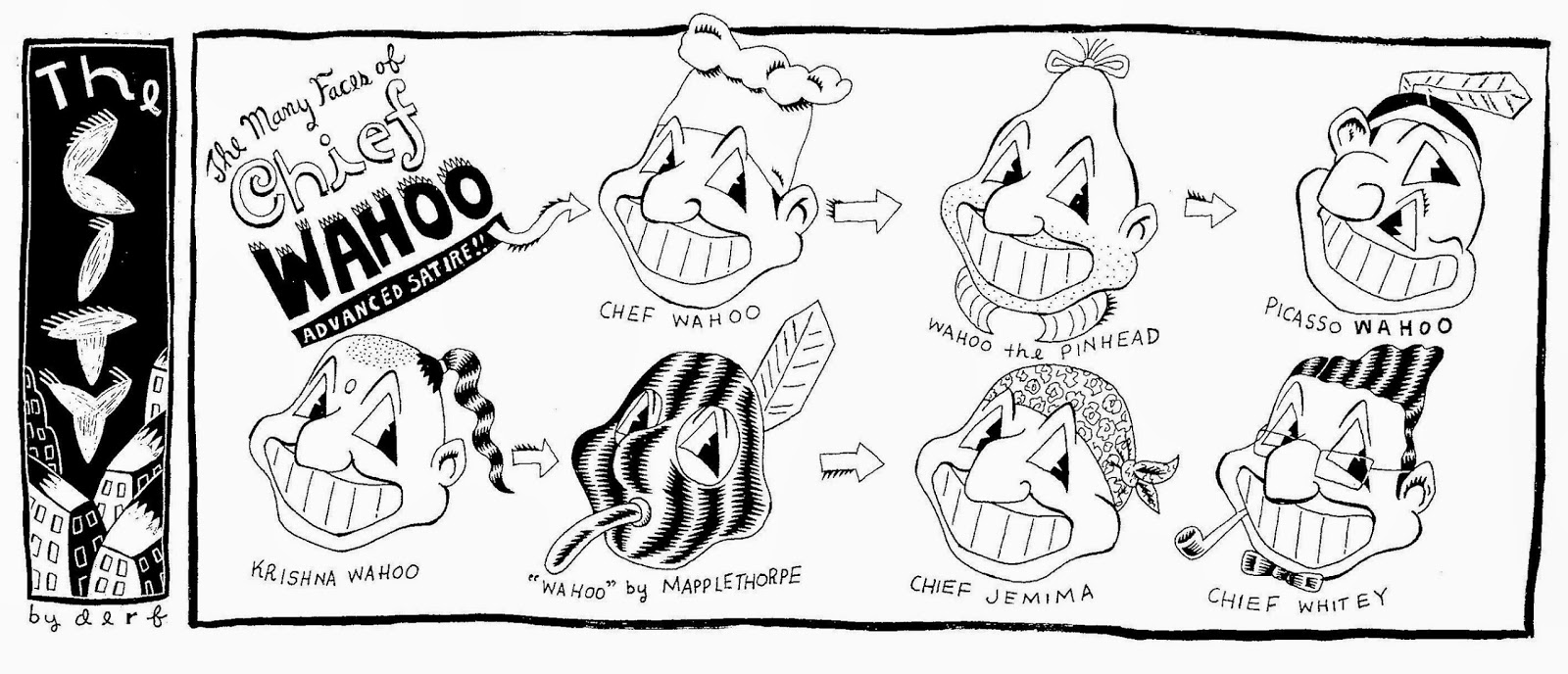

The Many Faces of Chief Wahoo. Advanced Satire!! by Cleveland artist Derf Backderf.

The Many Faces of Chief Wahoo. Advanced Satire!! by Cleveland artist Derf Backderf.

Rose Bouthillier, now curator at Saskatoon’s Remai Modern, lived in Cleveland for 4 years, working as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art. “How to Remain Human,” a group show she curated at the MOCA in 2015, included work by non-Indigenous Cleveland artist Derf Backderf, a prominent graphic novelist and political cartoonist who has been making satirical versions of the Chief Wahoo logo since the 1990s. Bouthillier shared her thoughts on the mascot and team name controversy over email:

“If Cardinal’s filings can shift how people see, altering their emotional and social connection to a form, that will go a long way in moving the dialogue forward. The possibility of an actual legal ruling, or financial penalties, might be able to spur action faster.

“The defenses for keeping the team’s name and mascot—nostalgia, standing up to elitist ‘PC’ liberals, and preservation of corporate/entertainment profits—represent beliefs that permeate large parts of American society.

“Acknowledging the problem with the name/logo means confronting so much more. A common argument for keeping them is that there are more pressing and urgent issues to deal with. That’s a defeating approach that fails to acknowledge how “symbolic” issues perpetuate ‘real’ ones. Artists, designers and architects are constantly confronting humanity, unsettling our comfortable positions, and proposing alternative ways to relate. Cardinal’s challenges have raised long-standing questions in new way, and I hope the momentum they generate will lead to change.”

The lead image illustrating this story shows caps emblazoned with stereotypical depictions of Indigenous heads and embroidered with racist slurs commonly used against Indigenous peoples. The work, titled Interventions, is by Halifax-based Mi’kmaq artist Ursula Johnson, and she describes it as a “commercial product intervention series about discriminatory iconography in sports memorabilia.” “I feel that the usage of this iconography leads to further perpetuation of stereotypes,” Johnson told me over email.

Kaiatonoron Bush. Courtesy CBC.

Kaiatonoron Bush. Courtesy CBC.

Kaiatanoron Bush, a Mohawk artist from Montreal and a student in OCAD University’s Indigenous Visual Culture program, recently helped to design a T-shirt that translates the ubiquitous “Toronto vs. Everybody” shirt into Mohawk. We asked her via email for her opinion on the Cleveland team’s mascot. She said:

“There is no place for this kind of discrimination in Ontario or in Canada for that matter. Visibility and accurate representation are crucial to building positive relationships and understanding between everyone who lives on Turtle Island. We cannot build these positive relationships unless there is mutual respect. This mutual respect cannot exist if Indigenous people are depicted in the same fashion as ‘Chief Wahoo’ and are all lumped together as ‘Indians.’ We are not ‘Indians,’ we are Onkwehonwe, we are Anishinaabek. We have many names and ‘Indian’ isn’t one of them. The use of ‘Tar Babies’ in marketing became inappropriate some time ago, so I do not see why it is appropriate to use the face of a “Red Indian” to market a baseball team. ‘Chief Wahoo’ needs to retire.”

Ryan McMahon on stage. Courtesy the Breath Films

Ryan McMahon on stage. Courtesy the Breath Films

Ryan McMahon, a Winnipeg-based Anishnaabe comedian and owner of podcast network Indian and Cowboy, proudly wears his “Caucasians” T-shirt on stage. “I’m a former athlete, so I know what sports are all about and about the power of role-playing,” McMahon told me over the phone. He wants Cleveland to step up and make a change. “If a sports team took a stand, imagine what kind of champion that team could be.”

“Some people will say this is an extreme view, but there is a direct correlation between this and the missing and murdered Indigenous women,” McMahon told me. “It’s about dehumanizing Indigenous people.”

Indeed, there have been multiple studies that clearly demonstrate the causal effects and mechanisms by which offensive mascots influence the psychological wellbeing of Indigenous peoples. Study after study after study after study after study. But is it even necessary to quote such statistics? In McMahon’s view, “Indigenous people have said it’s ugly, and sports teams, with their lucrative resources, have multiple jerseys per season. At the end of the day, if you just don’t care that your caricature is offensive, there’s no room for a conversation. The conversation is morally bankrupt if we’re not talking about making a good and just society for all.”

McMahon would also like the Blue Jays to break their silence on the matter and release a statement. Interviewed on CBC’s As It Happens, he said, “What is the Blue Jays’ response to this as an organization in Canada under this project of reconciliation? How does it engage with the Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe, Huron and Wendat communities whose land they built the [Rogers Centre] on?”

Whatever the outcome of today’s game, the Cleveland team will eventually return to their own home stadium: the ironically named Progressive Field, which will hopefully serve as a suitable venue for some large-scale introspection.

With files from Leah Sandals. This article was updated on October 19 to include comments from Rose Bouthillier and an image from Derf Backderf.

Ursula Johnson, Interventions, 2016. Photo A.Y. Taylor Photography

Ursula Johnson, Interventions, 2016. Photo A.Y. Taylor Photography