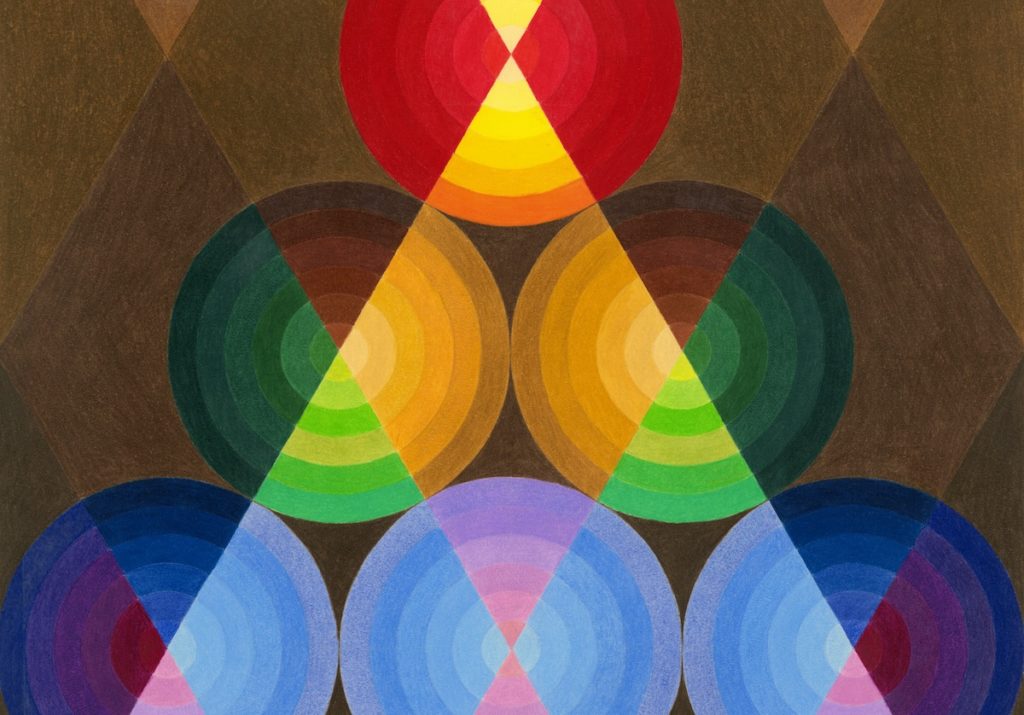

Perfect squares are mathematical abstractions that imagine a number being multiplied by itself in order to grow exponentially. At the architectural midpoint of the University of Toronto Art Centre, three contiguous square rooms hosted the first Canadian solo exhibition of work by Latvian-born, Montreal-based artist Zanis Waldheims (1909–93). “The exhaustive thought,” curated by Xenia Benivolski, presented a focused yet exuberant selection of geometric colour-field works created by Waldheims in the 1960s and ’70s. His pencil-crayon-on-paper abstractions oscillate between complementary and analogous palettes in systematically expansive variations that ripple beyond the edges of the picture plane. Gradual tonal shifts bloom into optic planes that are conceptual rather than painterly in their disciplined and consistent approach. The drawings hung in groupings of two, three and four, with the exception of a horizontal display that paired almost identical drawings dominated by bright blues and reds. Inside these images, Waldheims reimagines the world through a subtle palette shift that trades greys for flesh tones in the gradation pattern at the bottom of the compositions.

The world outside the images is much harder to shift at the moment: Toronto entered a COVID-19 grey zone and went into a second lockdown two days after I saw the show.

Benivolski’s research on Waldheims’s life and work contextualizes these abstractions in the aftermath of a series of brutal historical events that would have been just as difficult for the artist to foresee. Waldheims, educated as a lawyer, witnessed and fled two world wars and passed through United Nations rehabilitation camps in Germany before eventually settling in Montreal. Once there, he set to work establishing what, at that point, was not yet called a research-based practice. But “The exhaustive thought” displayed evidence of thorough research, including Waldheims’s copy of Bertrand Russell’s Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy alongside other passionately annotated book pages, detailed preparatory works and colour explorations. From these notes and sketches, Waldheims created hundreds of images that sought to give a sense of his investigations into the overlapping relationships across different kinds of knowledge: math, history, philosophy and linguistics.

Installation view of “The exhaustive thought” at the Art Museum University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Zanis Waldheims, #220, 1969. Pencil crayon on paper. Courtesy Yves Jeanson.

Zanis Waldheims, #416, 1980. Pencil crayon on paper. Courtesy Yves Jeanson.

Installation view of “The exhaustive thought” at the Art Museum University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Installation view of “The exhaustive thought” at the Art Museum University of Toronto. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In presenting Waldheims’s work as process, “The exhaustive thought” contributed to a recent yet urgent re-evaluation of the ways abstraction is exhibited in museums, expanding genealogies of non-figurative practice and recognizing figures who do not fit within established art historical narratives. “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” at the Guggenheim in New York made sense of Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural swirls through the painter’s Theosophy-inspired compositions. The rehanging of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection of abstract paintings, titled “Epic Abstraction,” acknowledged the work of artists like Carmen Herrera and Sam Gilliam alongside that of Jackson Pollock and Bridget Riley. “Spilling Over: Painting Color in the 1960s” at the Whitney Museum of American Art staged a bold transgression of the very categories of figuration and abstraction by placing Emma Amos next to Helen Frankenthaler.

My own practice as an artist reconsiders abstraction as both form and field echoing the intuitions that led these painters toward a committed pursuit of non-figurative strategies. I follow an untranslatable compositional drive to create minor forms of abstraction using ephemeral materials, context-responsive processes and relational approaches. In my “duet” with Jack Bush, an exhibition at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery and Art Gallery of Peterborough, I sought to engage in questions of difference and continuity across generations of artists working through abstraction in Canada. Bush boldly and prominently embodied the experimental ethos of post-painterly modernism in this country. I am a Guatemalan refugee, now Canadian citizen, turning away from figuration to resist the tendency to make identity into the kind of multicultural currency that cements Canada’s shameful colonial project. “duet” staged a dialogue between our compositional approaches that was neither patrilineal nor adversarial, but that allowed Bush and I to make contact across time.

In “The exhaustive thought” I found questions that echoed those in “duet” regarding the relationship between exile and abstraction—although we arrived at our work through different paths, at different times and with different technologies of visualization. Of course, a cause-and-effect relationship between an artist’s experiences as a refugee and a commitment to abstraction cannot be directly established. Yet learning about Waldheims’s work makes the question of what could lead a refugee to resort to non-figurative visual languages continue to resonate for me. The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada places the burden of proof on claimants, compelling us to narrate our journeys with legibility and credibility. That is how refugees become settlers.

Who, then, is allowed to refuse content and maintain a tangible relationship to the incalculable? Who claims abstraction? Any attempts to engage with these questions insist that we imagine that those who are dispossessed by history are not exclusively defined by need, but indeed have desires.

Zanis Waldheims, #209 (detail), 1969. Pencil crayon on paper. Courtesy Yves Jeanson.

Zanis Waldheims, #209 (detail), 1969. Pencil crayon on paper. Courtesy Yves Jeanson.