Following the initial publication of this review, BACA expressed concern about some of the claims made. Their concerns and our corrections have been added to the errata at the end of the text.

There are a few lines of thought that I want to lay out before I begin discussing the Biennale d’art contemporain autochtone—herein referred to by its shorthand BACA—the fourth edition of which ran at various venues in Montreal and Berlin this summer. First, the care, intelligence, and dedication that curators Niki Little and Becca Taylor put into organizing the biennale. Second, the uneasy environment of the current racial climate in Quebec for an organization such as BACA. The third line of thought is related to the shortcomings of BACA itself, at the head of which stands founder, president and director Rhéal Olivier Lanthier. In the preface of the BACA catalogue—a preface that appears before Little and Taylor’s curatorial text, and first in French—Lanthier identifies as a French Quebecer. My eyes widened when I saw Lanthier nod to his distant “ancestors,” one of whom he identifies as Onotawa’ka. The claiming of a colonized status in order to negate one’s role in colonial violence perpetrated on Indigenous communities on Turtle Island is a common settler move to innocence, as Eve Tuck might say.

Laying out these intentions, I hope to evade any confusion about my adamant support of the work of Little and Taylor, and the Indigenous art historical importance of their curatorial project titled “My Sister”—a package that I believe is the intellectual property of Little and Taylor and should be separated from the administration and infrastructure of BACA. Over the last year or so, I have been continually asked by my colleagues in art industries—curators, artists, critics and theorists within Canada and the United States—about the “Indigenous art trend” in Canada. I cringe every time. Indigenous art was, for centuries, the only art on Turtle Island. Indigenous peoples are due more than a moment to return Indigenous art to where it would have been if Indigenous territory, life and love had not been interrupted by colonialism. That said, what’s exciting is that Indigenous art in 2018 has seemed deeply rooted in the principles of rematriation—a term I borrow from the arts collective bearing the same name, whose art exhibits, happenings and uplifting memes featuring community have showcased positive representations of Indigenous women and recentred women’s knowledge within Indigenous communities.

Jeneen Frei Njootli and Tsēmā Igharas, some of ReMatriate’s founding members, consider the intimacy of kinship and Indigenous siblinghood. Alongside the first page for Little and Taylor’s curatorial text, “To and for One Another,” appears an image of Frei Njootli and Igharas’s performance sinuousity (2016). The pair is bound together by what appears to be brightly coloured survey tape and fabrics, which they have also braided into one another’s hair—a little bit of old-school NDN love, mixed in with some city-kid skid flare.

Little and Taylor’s curation was particularly successful because of their refusal to acknowledge cisgender straight men, whom I have known to be at the centre of Indigenous art since I opened my first art history book and read the names of the men we are told to pay our respects to, but who never seem to pay their respects to us, to the community. Of course, women, non-binary and trans folks have always been present and making art within Indigenous communities, but you’d be remiss to argue that they were ever afforded the same level of exposure as the big boys. As Leanne Simpson wrote recently about Facing the Monument at the AGO: given Rebecca Belmore’s impressive career, it seems unfathomable that it is her largest solo exhibition to date. But we all know why, writes Leanne. Similarly, we are just beginning to see Shelley Niro get acclaim and prestigious solo retrospectives for her impressive body of work, most notably her recent Scotiabank Photography Award show at the Ryerson Image Centre.

Don’t get it twisted: there is a difference between cancelling men and acknowledging that Indigenous communities need to de-centre toxic forms of masculinity—this is what Little and Taylor achieved seamlessly with their curation of “My Sister.” The big boys might call such a curation soft talk, but probably just can’t understand how fucking punk rock a lens that excludes them, that excludes toxic-masc ways of working, can be. To those men I would say, it’s OK, boo. As Janelle Monae would say, in this deliciously queer femme moment that is trending in cultural industries throughout Turtle Island, not just in NDN art: ’Cause boy it’s cool if you got blue / We got the pink.

Toxic-masc centricity in Indigenous art is frustrating because of the love that positively emanates from art produced by communities of Indigenous women, trans and non-binary people who hardly ever achieve the same reach as the men. This love is found at the heart of Little and Taylor’s “My Sister,” which they were adamant was a curation by and for their sisters, opening the term “sister” to encompass whoever identifies with it, and those whom they long witnessed labour in care over, and for, one another. In care, we carry our sisters, write Little and Taylor in their curatorial text. “My Sisters” represents a shift, a new era, a refreshed lens and a disruption to identity politics’ reign in Indigenous art, to paraphrase Richard Hill.

Why isn’t the organization listening to its Indigenous board? Where is the Indigenous community, generally, in BACA’s organization?

The works exhibited connoted a respect of intergenerational knowledge sharing and the legacies of Indigenous art communities. At the opening night of BACA’s Art Mûr edition, the room was packed wall-to-wall—a rare occurrence in Montreal. (Seeing many of my respected mentors at the events, present and showing their support of emerging curators and artists, let me know that there were many peoples before my generation who long did this work of making space for marginalized voices, and who have graciously passed us the torch.) Uzumaki Cepeda’s immersive room made of fun-fur was an audience favourite, and had children rolling around in it all night—some of the only art they engaged with. Jade Nasogaluak Carpenter’s soapstone carvings of objects such as cigarettes, lighters, Listerine bottles and tampons were a nod to traditional art methods that they attempt to reclaim and also make relevant to their northern-diasporic experience living in Calgary, Alberta. An empty table with markings for place settings appeared in front of Caroline Monnet’s Creatura Dada (2016), a video artwork featuring women from Monnet’s family and community eating a luxurious dinner, dressed in luxe fashions. The women are an intergenerational snapshot of Monnet’s kin, including Alanis Obomsawin and Monnet’s sister, artist Emilie Monnet.

Activism was a central theme of Little and Taylor’s curation for BACA at the Musée des beaux-arts de Sherbrooke. Beaux-arts is a contentious term for me: I associate it with pretty art, and that community of folks who will curate retrospectives of the Impressionists until someone tears every last Renoir from their cold, dead hands. Beaux-arts doesn’t have a race consciousness. Well, except for orientalism, along with all its subject-object binaries that always seem to play to the sensibility and aesthetic tendencies of white folks. But what occurred at Beaux-arts during BACA was an intervention on said community. Joi T. Arcand’s The Beautiful NDN Super Maidens (2014) took up an entire wall alongside her NDN super-maiden trading cards. Known for her community-based, sexual-health art actions, Erin Konsmo, a youth activist who trained on the land under Christi Belcourt, exhibited a series of posters titled Landbody (2018). The posters towered as high as the French-colonial style columns inside the gallery. A series by Kali Spitzer of Indigenous women photographed in the style of anthropological, archival prints perhaps poked fun at the Québécois Beaux-arts crowd, who would love nothing more than to imagine Indigenous peoples into our graves.

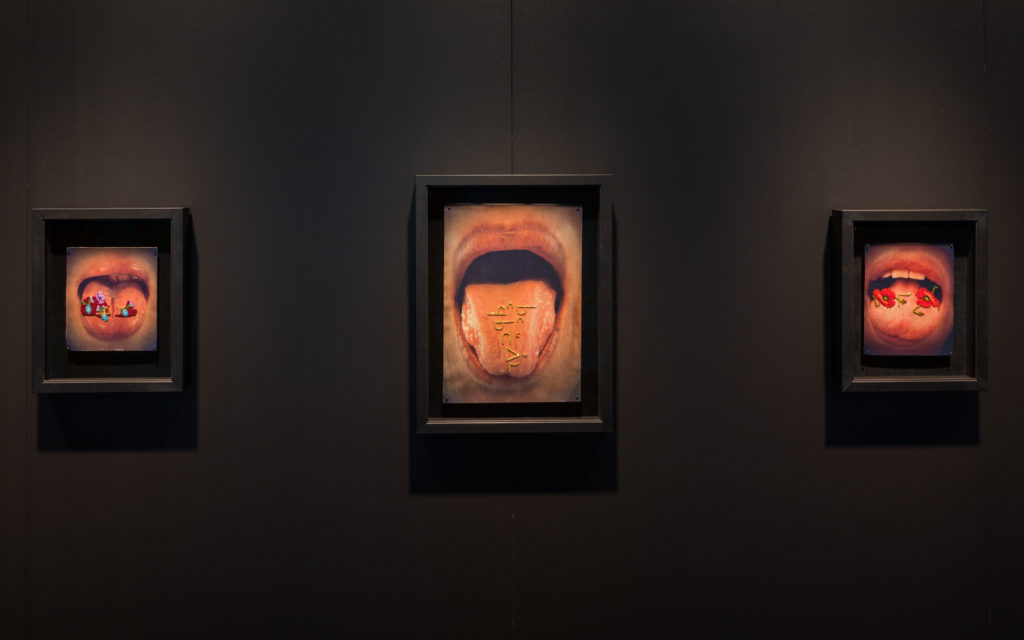

Still, the problematics of Québécois arts communities did seep into my overall experience of BACA, making me aware of the larger tensions of hosting such a biennial within Quebec, wherein the disappearing NDN is still a very real trope to be contended with. I felt grateful to witness a beautiful curation at La Guilde, where a standout work was no doubt Catherine Blackburn’s se (2017). The uncomfortable visual—of a tongue as a pincushion with a syllabic symbol as its pins—is feminist affect at its finest, a reminder of the physical pain of Indigenous language loss, and the struggle to relearn Indigenous languages. But watching Québécois communities interact with the tattooing ceremony that occurred at the La Guilde opening, for instance, was a reminder that this kind of love is generally an awkward fit in Quebec. Some of the audience members callously interacted with ceremonial space to ask questions, push forward through the crowd, or interrupt the ceremonies at hand—some even placed their drinks on the tattooing table. It was a reminder that Québécois often look to Indigenous culture with voyeuristic curiosity, regardless of how tenderly it is framed. But Little and Taylor’s resolve to still curate to and for their sisters did provide a grounding, if only just as femme NDN visibility in the space. In care, I was carried by Little and Taylor.

Even if Indigenous peoples are at the core of an event, if Indigenous art happenings are embedded in settler art cultures, those events are not working in an Indigenous way.

This feeds into a larger conversation about the state of arts organizing and funding in Quebec. Time and again I have witnessed my Indigenous arts colleagues in Quebec apply for funding in Montreal or at CALQ, make the shortlist, but ultimately lose out to a white, French-speaking Quebecer. It’s like Quebec arts-funding bodies want to acknowledge Indigenous peoples only as objects of fascination, rather than ground those acknowledgements in respect for our cultures and ways of working. This cultural perspective would seem to be echoed by the recent controversy around Robert LePage’s Kanada, a now-cancelled theatre production about Indigenous peoples from Turtle Island that included no Indigenous actors. And this on the tails of his wildly offensive show SLAV, all while CALQ recently, and quite hastily, rolled out a new Indigenous-specific funding stream entitled Recognition—you can’t even make this stuff up. It will be interesting to see how those funds are juried to ensure that they are going to Indigenous-led projects. Because there is a difference between working in Indigenous ways, and working in Indigenous art. And the latter can bleed into identity politics.

I was shocked to hear that this is the first year all the artists who participated in BACA got paid. It should be noted that the first three editions of BACA were commercial gallery projects and therefore not subject to imposed minimums of CARFAC. But the ethics around bringing Indigenous knowledges into Canada’s institutions, and the appropriate compensation for doing so, has been a contentious ethical conundrum for many knowledge producing communities, such as research, art industries, and publishing. It was appalling to get wind of misogynist treatment of this year’s biennial curators.

A show entitled “Conflicting Heroes” appeared at BACA Berlin during the 4th BACA’s exhibition in the Montreal region and Sherbrooke, and the works there seemed chosen to respond to, or correlate with, works shown at BACA in Quebec. Though information for the Berlin show is housed on BACA’s website and it is therein advertised as presented by BACA to coincide with the Berlin Biennial, “Conflicting Heroes” was curated by Mike Patten and is separate of BACA in Quebec.

In Berlin, I noticed that Dayna Danger’s artwork appeared on a small-scale. As someone who writes about Danger’s work frequently, I know that scale is of the utmost importance to the work’s themes. Seeing Danger’s work curated this way reeks of decision making by someone concerned with collectors. In bringing such sensitive and emotive concepts to a space like Germany, wherein voyeurism toward Indigenous art is perhaps at its apex, BACA’s director was certainly not concerned with the comfort of the Indigenous peoples involved. Rumours circulated about the organization not printing a translation of the catalogue into Indigenous languages, arguing there “wasn’t enough time,” and that the catalogue was “already in print when the translation came in,” though they prioritized translation into another colonial language—French. It should be noted that, in Quebec, French languages are required to appear before English in public documents and signage. With this reference I am pointing to a larger problem within Quebec wherein French sovereigntist policies are often positioned to supersede Indigenous sovereignties and the needs of Indigenous communities. The Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and their “Tiohtià:ke Project,” who hired Little and Taylor as curators for the 4th BACA biennial, will not be participating in further editions of BACA as a result of all the aforementioned tensions.

Is BACA, at its heart, an Indigenous organization? There are Indigenous peoples, whom I deeply respect, who sit on its board and whose ways of working I’m familiar with. I know that BACA doesn’t represent the community-engaged ways of working we observe among ourselves, as Indigenous peoples, in Montreal. Is BACA listening to its Indigenous board? Where is the Indigenous community, generally, in BACA?

In my work in the art industry and publishing, I am constantly being told, when I point out unethical ways of working, this is just how things are done; or, it’s not that big of a deal, just get over it. Colonialism, industry, is the ultimate gaslight. Just because something has always been done a certain way doesn’t make it OK. With its current director, in its current manifestation, BACA as an organization is one defined by identity politics and little ongoing responsiveness to local Indigenous communities. There is a difference between recognizing and representing Indigenous community, and working to transform institutions to be more equitable to Indigenous peoples. In these, the high holy days of “reconciliation” in the arts, arguing that this is just the way things are done doesn’t cut it anymore. If Indigenous communities are not benefiting from the Indigenous art biennial, from Indigenous art initiatives in Canada, generally, who is?

Clarifications and corrections were made to this article on September 8, 2018. The original review indicated that the fourth edition of BACA happened in locations in Montreal and Berlin. The text has been edited to indicate the show “Conflicting Heroes,” which appeared at BACA Berlin, was curated by Mike Patten separate from BACA Montreal and Sherbrooke. The original review’s implication that BACA was not listening to its Indigenous board members has been changed so that the text more clearly represents this as the author’s perspective, not a factual assertion that the organization is not listening to its Indigenous board members. The original review implied that Caroline Monnet’s work Renaissance (2018) appeared in front of her table installation at the Art Mûr show for the fourth BACA. The work that appeared in front of Monnet’s table installation was actually her video Creatura Dada(2016). The original review stated that artists who participated in previous editions of BACA were not paid. Some of the artists were paid some time during the first three BACAs, and it has been noted herein that, because editions one through three were commercial projects, BACA was not required to pay its artists. The original review referred to the director arbitrarily picking works from Little and Taylor’s curation to ship to other venues such as BACA Berlin. Reference to the director of BACA in relation to curations of BACA has been removed. This review has been edited to remove any implication that the organization chose to print the catalogue preface in French first. The original review references BACA’s “adamant refusal” to translate the exhibition text into an Indigenous language; the exhibition text was translated, but did not make it to print. The original review stated that there were murmurs that BACA is set to open two more international locations, an unsubstantiated reference that has since been removed.

On September 8, the following incorrect information was added to this article: “I was concerned to hear that the organization was claiming ownership over a curatorial package created by Little and Taylor, shipping it to other galleries, such as the Art Gallery of Mississauga for a now defunct run of the curation, without the consent of Little and Taylor.” It has since been removed.

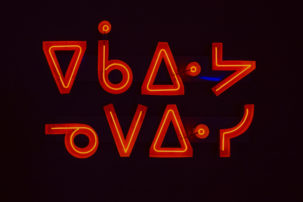

Catherine Blackburn, se, 2017.

Catherine Blackburn, se, 2017.