Note to the reader: I have begun this monthly column to think out loud in public about questions and controversies arising from my current research for a book about contemporary Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995. Let’s start things off with a provocative question: Was Indigenous art better in the 1980s and early ’90s?

During a recent conversation a friend bemoaned the current state of contemporary Indigenous art. We were talking about the research I have begun and how excited I am to be re-visiting texts and artworks from the 1980s and early ’90s. Among other things, that period was defined by the struggles of the first large wave of art-school trained Indigenous artists to make space for themselves in galleries, museums and magazines. The best works of those artists—James Luna, Rebecca Belmore, Jimmie Durham, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Edgar Heap of Birds, Edward Poitras, to name only a few—changed how we imagine ourselves and our place in the world.

My friend, who has been involved with contemporary Indigenous art for many years, was concerned, however, that the radicalism of the artists of that generation has too often taken a turn for the worse toward a conservative identity politics. This might seem like a shocking perspective given the celebratory atmosphere surrounding the current (relative) institutional success of Indigenous art. There is a genuine sense of debt to artists who cleared space for those of us who followed and we often want to see ourselves as helping to continue or fulfill their projects. To me, that makes asking critical questions all the more urgent.

So, have the successes of the radical critical project of the “Indigenous Renaissance” of the 1980s and early ’90s been consolidated into a mannered triumphalism? Are questions of identity now less likely to be opened up and explored than to be regulated and constrained by rampant rule-making and enforcement in the name of tradition? Might it not, in other words, be a good time to revisit that period to see whether it holds possibilities that have been elided by narratives of institutional success and identity politics?

Having begun with a deliberate provocation, I’d like to step back a bit. Nostalgia is treacherous—the past always has the advantage—and pitting artists of different generations against each other helps nobody. I don’t think that was my friend’s point.

While I sometimes despair at how often the work of younger artists is merely a pale echo of earlier works—addressing the same questions of representation in the same way—I don’t think this is a generational failure. It is hard to make good art that gets out in front of new issues and perspectives, and each generation only produces a minority of artists who are able to do so. Having recently spent a lot of time looking through old exhibition catalogues I have seen that, along with iconic works by artists like Belmore and Luna, there are many banal, forgettable efforts by artists that we have, well, forgotten. That’s how nostalgia operates.

Likewise, among the familiar gestures and clichés of today there are many outstanding artworks and texts that are opening up new questions and possibilities. The problem is that there is now also a lot of space for gestures that were radical several decades ago, but have become conservative in our changed circumstances. At times, efforts to consolidate institutional power have tended to support conservative rather than progressive work. In accessing many of the new opportunities that have arisen, toeing the party line is too often the safer choice, and safe choices lead to bad art.

We also need to consider the larger social context of Indigenous cultural revival. The arts played a role, but by far the most influential institutions of this revival began with the creation of “Indian” Friendship Centres and American Indian Movement Survival Schools in the 1970s. These efforts evolved fairly quickly into state- or band-funded Indigenous-run social-service agencies and cultural centres.

The latter development occurred in precisely the period that I am researching and, oddly enough, I had front-row seats to the phenomenon. My mother, a professor of social work at the University of Manitoba, was involved in establishing one of the first Indigenous-run social-service agencies in Winnipeg in the early 1980s. In the 2000s, my wife worked for a number of years running a youth art program at Native Child and Family Services in Toronto where I would occasionally volunteer or simply drop in to hang out.

All of these institutions developed “cultural” programming and because of the high level of Indigenous involvement with social services (both receiving and delivering) the reach has been very wide. Some of this programming has been developed and delivered by thoughtful and knowledgeable people, but much of it seems to be invented on the fly, often with a generous salting of pan-Indian new-age nonsense and hold-over assumptions from residential-school religious education smuggled in the back door. In my experience, the less knowledgeable the provider, the more anxious that person tends to be about their Indigenous “authenticity,” and the more dictatorial they become regarding the proper performance of Indigenous identity.

I actually think the artworld is less susceptible to this oppressive essentialism than many other places. The people who appoint themselves to govern the boundaries of our identities often take up more space in the conversation than they genuinely occupy and, sadly, people who hold a different view are sometimes cowed into public silence. But art ought to be the place we can work out difficult questions and broach new ideas in public.

How does this all fold around to inform a re-examination of the 1980s and early ’90s?

So far—and I am learning as I re-read the literature—I can identify a number of key themes in art and writing from that period. One is certainly cultural revival. Another is the critique of colonial representations that is both targeted to specific tropes and to the broader problem of lack of space for Indigenous art and culture in public discourse. This, in turn, is linked to a project of an Indigenous-focused institutional critique and advocacy for institutional access.

All of these themes have been developed with real intelligence, often evolving into genuine institutional change; one might even say (if the term hadn’t already been sullied by history) into a cultural revolution. But it may be that each revolution has potential dictators waiting in the wings to claim its legacy and usurp whatever bit of power has been freed up or redistributed.

For that reason, I want to add one more theme from this period to the mix—one that, oddly, seems to be expressed less now than then. This was the common insistence of artists of the time that their contemporary reality be acknowledged and valued. It was often an outright rejection of the salvage anthropology assumption that an authentic identity was only guaranteed by the mimetic reproduction of tradition. It also frequently involved a claim about the legitimacy of being interested and engaged with the wider world (absurd to have to claim at the time, even more absurd now).

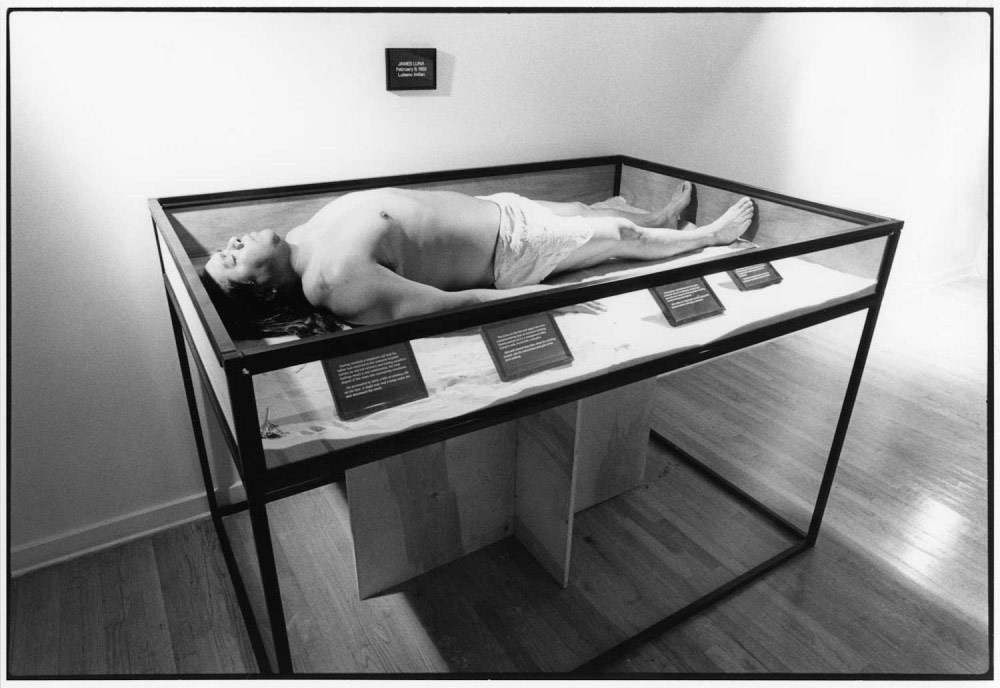

We can see that claim about engagement in the wider world in Luna’s inclusion of his Motown record collection when representing his life in Artifact Piece (first performed in 1987), or Carl Beam’s explanation of the juxtapositions of images at play in his collages: “if you have your own face next to a rocket if you have your own face next to the Sadat assassination, this, to me, implies that one…has to have personal responsibility for world events.” Or Shelley Niro insisting in a 1995 interview: “I think a lot of times Indian people end up stereotyping themselves. They…buy into the mushy, gushy image that is acceptable and, you know, it’s safe. Some people think that to be Indian, you have to do certain things, but I’m just saying that you’re Indian no matter what you do, but you have to decide what you want to do and you have to ask questions.”

If we can imagine each of the previous themes (cultural revival, colonial critique, and institutional access) shifted to various degrees by this last idea about contemporary realities—invisibly adjusted as though by a gravitational field—then we might be on to something. In Jimmie Durham’s 1988 article in Artforum, “The Ground Has Been Covered,” for example, Durham tracks both the problem of exclusion from a public sphere dominated by stereotypes and from contemporary reality in general: “I feel fairly sure that I could address the entire world if only I had a place to stand.”

Well, some ground has been cleared. Bring on the world.

Richard William Hill is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Studies at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver. If you have advice, information, documents or anything else that might help him with his research on Indigenous art from 1980 to 1995, he would be grateful to hear from you: richardhill@ecuad.ca.

This article was corrected on April 11, 2016. The original suggested that James Luna’s Artifact Piece was originally performed in 1985 rather than 1987.

James Luna's Artifact Piece, first performed in 1987, integrated a crucial insistence that the contemporary reality of Indigenous artists be acknowledged and valued, Richard William Hill writes.

James Luna's Artifact Piece, first performed in 1987, integrated a crucial insistence that the contemporary reality of Indigenous artists be acknowledged and valued, Richard William Hill writes.