“What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic” unearthed stories from Newfoundland and Labrador’s Afro-diasporic histories, including the province’s commercial involvement in slavery through boat building and the trade of fish, sugar, molasses and rum. Didactic and dialectic, the exhibition traced relationships between cultural memory and archival silence through works by Canadian artists Sandra Brewster, Shelley Miller and Camille Turner, and British artist Sonia Boyce, alongside artifacts and objects from Newfoundland and Labrador. British Ghanaian artist John Akomfrah’s epic three-channel video installation Vertigo Sea (2015) was also presented here, and its rhythms of modernity relating slavery, pollution and histories of migration acted, in part, as inspiration for the exhibition.

Guest curator Bushra Junaid selected items from The Rooms’ collections and archival materials, including a glass ointment bottle, a rum barrel and a pipe, to put alongside the contemporary works, connecting the past to the ongoing legacies of environmental racism and resource extraction that fuel provincial economic and cultural investments today. “What Carries Us” traversed embodied histories that leaked beyond the borders of the traditional archive, time-travelling through clothing, food, sound and image, to contend with Newfoundland’s role in the history of transatlantic trade.

The intimate power of cultural memory surged under the swell of material objects, like the stained suit and shoes of a young Black sailor from the early 1800s (found in L’Anse au Loup, Labrador, in 1987) laid flat in a glass box in a pocketed room off the main gallery. The only identifying notations on the garments are the initials “W.H.” etched into the owner’s right shoe with a pocketknife. These objects, bereft of historical detail and thereby haunted by a cryptic silence, became activated when contextualized by recent works such as Turner’s Afrofuturist video installation Afronautic Research Lab: Newfoundland (2019), which engaged with historical research through a contemporary performance practice.

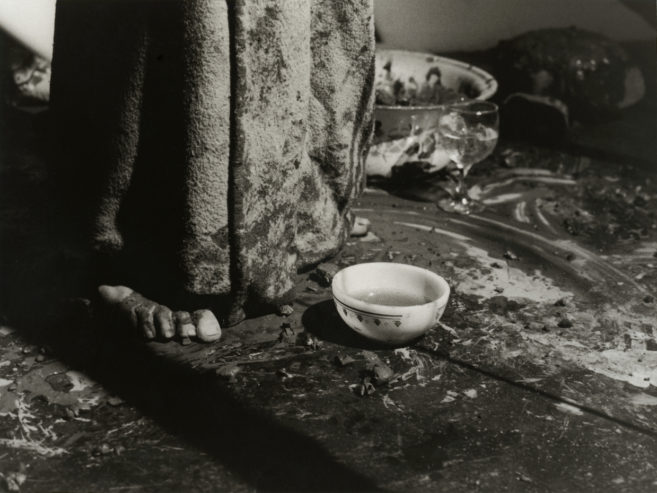

Installation view (detail) of “What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic,” The Rooms, 2019.

Installation view (detail) of “What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic,” The Rooms, 2019.

Installation view (detail) of “What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic,” The Rooms, 2019.

Many works took sugar and rum as subjects, including Miller’s sugar-tile mural, Trade (2020). Recalling Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese ceramic tilework, Miller’s depiction of the shipping vessel the A.V. Conrad applied the prominent blue-and-white designs to an organic frame of sugar tiles to contend with the relationship between sugar and colonialism. Sandra Brewster’s Essequibo 1 (2018), a photo-based gel transfer that uses an archival image smeared by brilliant orange-red hues, references one of Guyana’s largest rivers and its role in the sugar trade, offering a powerful reflection on the intimacies of water and place. In Heirloom (2017), a glass jar of dried fruit soaked in rum and wine, Brewster meditates on the passing of intergenerational knowledge in Caribbean families through foods that connect histories of migration and cultural tradition. Here, sugar and rum demarcate the cultural links between the Caribbean and Newfoundland and Labrador, and, as subjects, represent the often paradoxical interlocking of nourishment and extraction, care and harm that define intergenerational memory. Likewise, Sonia Boyce’s video and sound installation Crop Over (2007)—a meditation on the annual Barbadian festival Crop Over, a celebration that originated in the sugar cane plantations during slavery— contends with the complex historical legacies of cultural traditions exchanged between Britain, West Africa and the Caribbean.

“What Carries Us” presented a challenge to a provincial self-portraiture that is largely invested in whiteness, tourism and resource extraction—extensions of Newfoundland and Labrador’s historic contributions to slavery through industry and colonialism. It refused the depths of forgetting, instead opening an archive through somatic modalities that offered an embodied reading of the past, changing the way we carry histories and understand the present.

Installation view (detail) of “What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic,” The Rooms, 2019.

Installation view (detail) of “What Carries Us: Newfoundland and Labrador in the Black Atlantic,” The Rooms, 2019.