In choreographer and “live artist” Dana Michel’s CUTLASS SPRING (2019), the black box theatre was whitewashed: the central performance space was demarcated by a white marley floor, upon which was a large white felt carpet and a grid of nine flimsy white plastic patio chairs. Closely encircling this sat the audience, perched on low risers. Against this white-on-white backdrop, the performance emerged from darkness. For the first couple of minutes, the lights emanated the lowest of lumens, and Michel’s entry onto the stage was visible only by the glow reflecting back off the monochrome scenography.

In her statement in the performance’s handbill, Michel asks, “How might I locate my sexual identity within a multitude of complementary and seemingly contradictory identities—as a performer, as a mother, as a daughter, as a lover, as a stranger?” Over the course of an hour, she worked through a series of gestures—propositions in response to this query. These gestures of discovery unfurled from a body that was varyingly restrained, exuberant, restricted, flailing, clumsy, strong, self-conscious, confident.

In the first movement, Michel, donning a woolen hunting jacket, black boots and some floppy shorts, planted herself on her knees on a furniture dolly. Shifting the weight of her body back and forth, she advanced incrementally across the stage toward the rows of plastic chairs. As the lights gradually grew brighter, Michel’s stoic, opaque rocking bloomed into a sexual bounce. A Beyoncé-esque shoulder shimmy punctuated this transition, and I was stuck with the lyric from “Countdown” in my head: “Grind up on it, girl, show ’em how you ride it.”

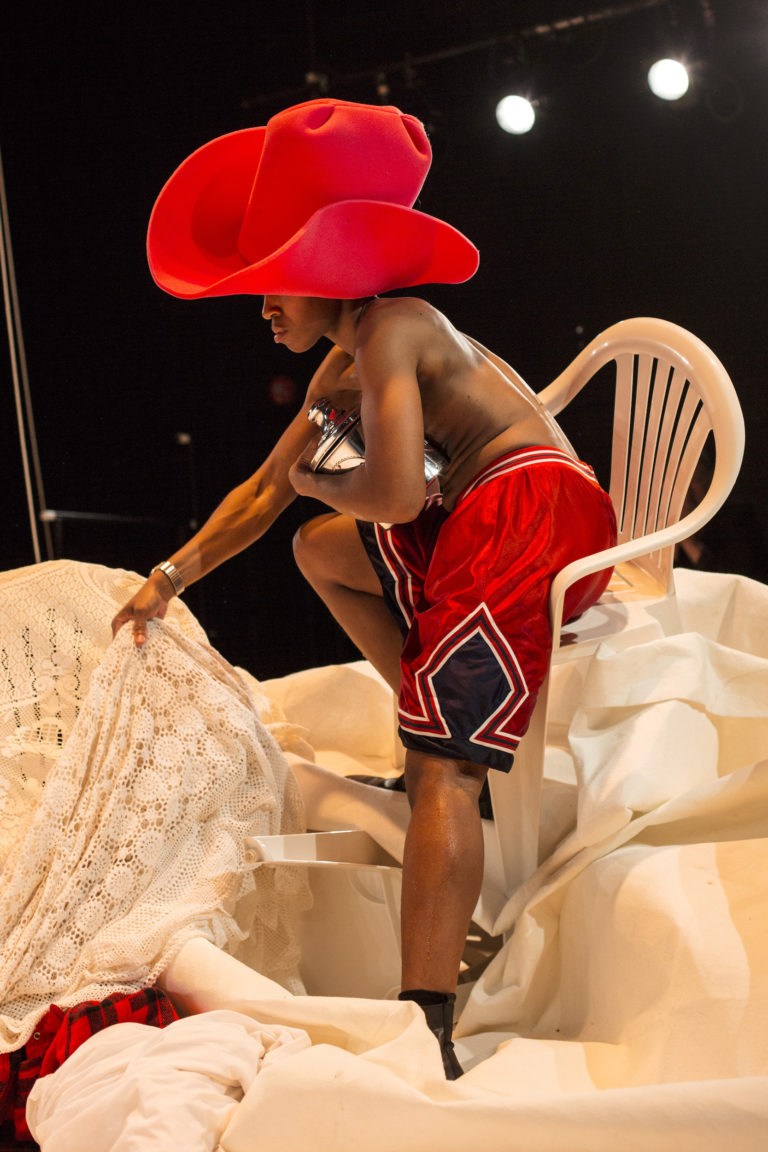

These transformations marked Michel’s journey of discovery in CUTLASS SPRING. When meaning, or even the audience’s reaction, became uncertain, Michel elicited a laugh (sometimes funny-ha-ha, sometimes funny-strange) or a moment of awe. In one such instance, she pulled out an oversized serving fork and waved it above her head like a riding crop. In another, she exited the theatre, back on that rolling dolly again, and for what seemed like an eternity, clanked around in the lobby with her big fork and a pot. At another point, she whipped out a giant red foam cowboy hat and gallivanted around the stage wearing only the hat, a gold chain, basketball shorts and her boots. Where these moments may not have contributed to greater legibility, they complicated and extended the contradictory identities that Michel inhabits.

Dana Michel, CUTLASS SPRING (performance documentation), 2020. Photo: Jocelyn Michel.

Dana Michel, CUTLASS SPRING (performance documentation), 2020. Photo: Jocelyn Michel.

As the performance progressed to its midpoint, the lights continued to brighten. It was here when the whiteness of this space became acute, uncomfortable even. In one segment, Michel enveloped herself in the large piece of white felt on the floor, only to reemerge and use the fabric to round up and wrestle the empty white chairs off the marley into a corner, behind the risers. Later, she dragged out a number of white sacks and proceeded to stomp and smash them, ejecting their contents—an electric hot plate, several bags of ice—across the stage. At first, she sashayed gingerly around the room, but later returned to centre stage with a dog leash to whip, kick and shove the objects across the floor.

In the performance’s final gesture, Michel donned a brown leather bomber jacket and brown leather pants, a look that exuded a kind of macho confidence. She returned to the stage on the dolly, this time standing and holding a rope that extended up to the ceiling and threaded back to a rug on the ground. The bell curve of the lights had them back to a dim glow and, although she was standing, Michel moved on the dolly with the same tentative, incremental advances as she did earlier. Here, her movements were guided by this rope, tied to a white curtain, which, as she inched closer to it, slowly raised up out from under the rug to be suspended in the air. It was a stunning and triumphant gesture; even where mechanics of the movement didn’t add up (though Michel appeared to use the rope as a tether to pull herself along, the rope couldn’t actually hold her weight), Michel struck a delicate balance.

Dana Michel, CUTLASS SPRING (performance documentation), 2020. Photo: Jocelyn Michel.

Dana Michel, CUTLASS SPRING (performance documentation), 2020. Photo: Jocelyn Michel.