Other Places: Reflections on Media Arts in Canada is a collection of essays, artist portfolios and interviews that demands attention. Through 33 contributions and an afterword, editor Deanna Bowen foregrounds perspectives from First Peoples, racialized, differently-abled, LGBTQ artists and administrators, voices often occluded in the Canadian national narrative. The volume is an important step in the long journey to decolonize Canada’s arts and culture sectors and reclaim sovereignty of one’s own image and representation. Bowen points out that the anthology is the “first iteration of what will be an ongoing project” to document the incredible work “of so many under-appreciated artists.” Indeed, from analyses of how survivance is embedded in the work of Indigenous artists, to explorations of performance as healing narratives, to spaces of intersectional feminism, immigration, censorship, queerness and trans body politics—and the importance of artist-led archiving—the anthology is the first book of this scope and breadth in Canadian media art history.

The volume opens with a gesture of respect and responsibility for the past by acknowledging a mistake made in 2017 when the Fall issue of Canadian Art announced the death of Cree artist Archer Pechawis. Here, Pechawis’s letter to the editors, titled “I Am Not Dead,” sets the tone for the volume: “please be careful with our community. We have a lot going on.” This is borne out in the rich lineup of contributions, brilliantly organized to create a space of conversation—with each other, but also with the reader, who is invited into this space of contestation and critique.

Erika DeFreitas, forgive me for speaking in my own tongue/to practice the study of

breathing, 2016. Two-channel video, colour, 11 min 02 sec. Courtesy the artist.

Erika DeFreitas, forgive me for speaking in my own tongue/to practice the study of

breathing, 2016. Two-channel video, colour, 11 min 02 sec. Courtesy the artist.

In many of the contributions, storytelling and personal histories are as important as methodology and academic scholarship. Personal reflection and lived experiences are woven together with scholarly references, embedding the local within the global as foundational art events and practices in Canada are framed within global struggles. Jason Edward Lewis’s interview with Kim Tallbear, Sylvia D. Hamilton’s essay on history and memory in African Nova Scotia, and Mark V. Campbell’s piece on Indigenous and Afro-diasporic hip hop point to the importance of former and concurrent struggles within diaspora (such as the Third Cinema movements of the 1960s and the British Black arts movement in the 1980s) when framing local stories. Zainub Verjee’s incredible recounting of the “making and unmaking” of the international film and video festival and symposium In Visible Colours, in 1989, reveals that these events could happen only because a racialized person cared and was there to get them off the ground!

In “For Iktomi,” Steven Loft’s touching tribute to Âhasiw Maskêgon-Iskwêw, we are reminded of the latter’s groundbreaking thinking around the “aesthetic of nexus,” through which Indigenous systems transfer knowledge and language, and connect to both present and future through the past. Language can even transcend speech, as Ricky Varghese and Francisco-Fernando Granados describe in their essay on Erika DeFreitas’s installation work about the language of grief and mourning. The remediation of photographs of suffering and their reworked performance into video installations is taken up in the work of other racialized Canadian immigrant artists who do not appear in this volume—such as Montreal-based artist Nadia Seboussi’s three-channel video installation Hidad (2015), which stages performances based on an iconic photograph taken during Algeria’s Bentalha Massacre of 1997 to impose movement from personal grief to collective compassion and activism.

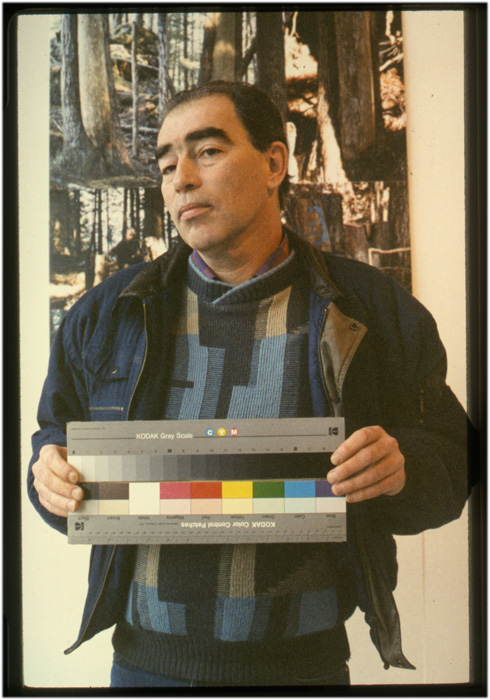

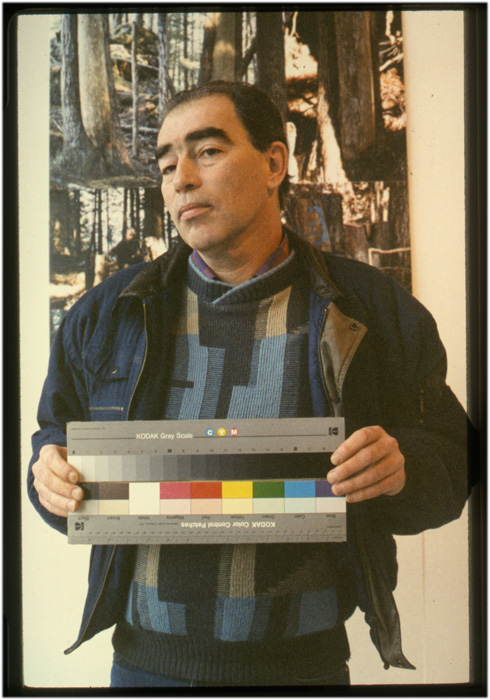

Mike MacDonald, 1990. Courtesy grunt gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

Amanda Strong, the making of How to Steal A Canoe, 2016. Animation, 4 min 10 sec. Courtesy Spotted Fawn Productions.

Richly illustrated throughout, and with artist portfolios by Amanda Strong, Mike MacDonald, Cindy Mochizuki, Jacqueline Hoàng Nguyễn and Cornelia Wyngaarden, Other Places could easily be called Our Places. It invites and provokes conversation with global artists and thinkers (for example, how can we not think of the work of Senegalese scientist and philosopher Cheikh Anta Diop when considering Maskêgon-Iskwêw’s “indigeneity of thought”?) and ultimately gifts us an important history lesson that we must share with current students and future generations.

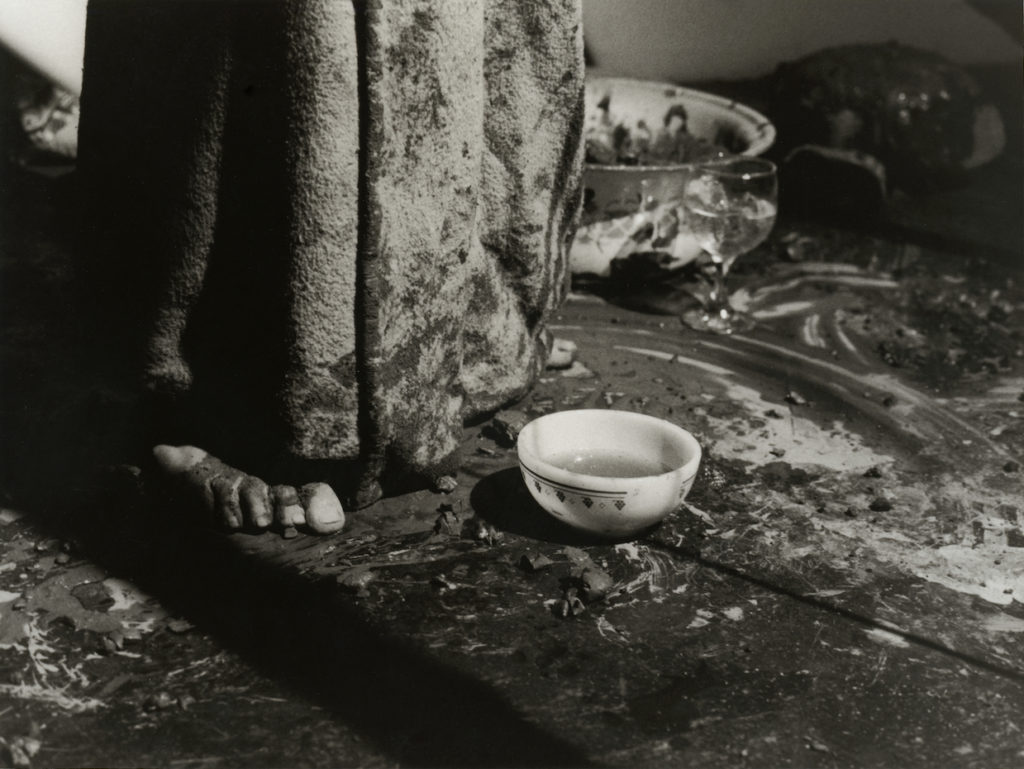

Âhasiw Maskêgon-Iskwêw, Âsowaha (performance documentation), 1995. Courtesy grunt gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.

Âhasiw Maskêgon-Iskwêw, Âsowaha (performance documentation), 1995. Courtesy grunt gallery. Photo: Merle Addison.