Some za’atar from last year’s Toronto Palestine Film Festival (TPFF) still sits in my pantry, za’atar that I couldn’t access from within the room I was quarantined in for two weeks. I’ve been attending the festival every year since 2017. Unlike the usual experience of being in the company of friends at screenings, I viewed this year’s films, and attended an insightful virtual panel on Cultural Suppression & Revival, in self-isolation.

On my first day after quarantine, I hopped on a bike to go to the plumb, a new member-funded DIY space that opened in September, to catch the last day of TPFF’s Local Pals Residency film screening. I made my way down a small alley and was greeted by a purple door. In a quirky basement space of hallways and ceiling pipes, I sat on a big black pillow to watch four films by emerging Palestinian filmmakers, made possible through TPFF’s inaugural residency program in partnership with Trinity Square Video and Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto. Leila Almawy’s Rumaan, Serene Husni’s Brown Bread & Apricots, Kalil Haddad’s The Beautiful Room is Empty and Rana Nazzal’s Something from there (all 2020) are explorations of kinship, land and the embodiment of memory. Relying on oral storytelling and family history, the films presented conversations that often felt too intimate, like I wasn’t quite supposed to be listening. Family members speak to each other, speak to their land, share their past: not quite dinner table conversations, not quite fleeting mentions of memories.

Lelia Almawy, Rumaan (film still), 2020. 14 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Lelia Almawy, Rumaan (film still), 2020. 14 min. Courtesy of the artist.

The story of Rumaan begins around 73 years ago, in Palestine, when Almawy’s grandfather was gifted a pomegranate seedling by a friend, and then started to grow, nurture and care for pomegranate trees. Decades later in Canada, Almawy’s uncle, Zaki, tries to revive and keep alive the seed that made its way here from Palestine and Lebanon. Interspersed with footage of him in his garden, Almawy walks us through Zaki’s relationship with gardening and his homeland, drawing a tender parallel between intergenerational bonds of care and resistance. How does one hold onto roots and stay grounded in diaspora? Almawy includes an interview with conservationist Vivien Sansour, who says, “We’re all seeds”—the pomegranate seed is a proof of lineage—“we didn’t grow from nothing.” Throughout Rumaan, Almawy shows how seeds speak to perseverance and preservation, and how the trajectory of a desire to tend and care for a life, no matter how small, is an arc of kinship and resilience.

Serene Husni, Brown Bread & Apricots (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Serene Husni, Brown Bread & Apricots (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.

In Brown Bread & Apricots, Husni invites the viewer to listen to her uncle Hammoudeh’s stories, coupled with moving images of pantries, home exteriors and old photographs. Dedicated to her grandparents and Hammoudeh’s parents, Aicha and Najeeb, Husni highlights the stories embedded in the seemingly mundane which tell of kinship, love and longing. At the age of 13, Hammoudeh’s dad put him in charge of his family’s two-week allowance as an attempt to change his troublemaker behaviour. Hammoudeh had 80 dinars to feed his three siblings and take care of the house. Close-up shots of jam jars, cheese, magdoos and green olives run onscreen as Husni lists items found in the pantries of Palestinian homes, characteristically never bare and the reason why Hammoudeh, being strategically cheeky, only bought brown bread for the house. The film’s dual naming, also titled نص كيلو مشمش meaning “half a kilo of apricots,” acknowledges what he bought for himself everyday and hid from his siblings, and what he might miss in Germany, where he is now. Shots of Hammoudeh’s recounting of that history often overlap with Husni’s narrative voiceover, reminding us that stories are passed on and live through verbal inheritance.

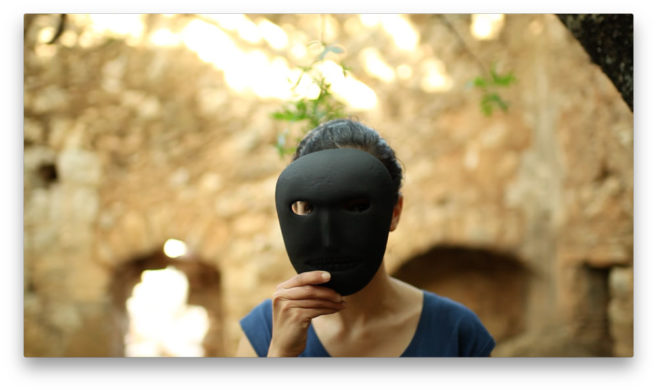

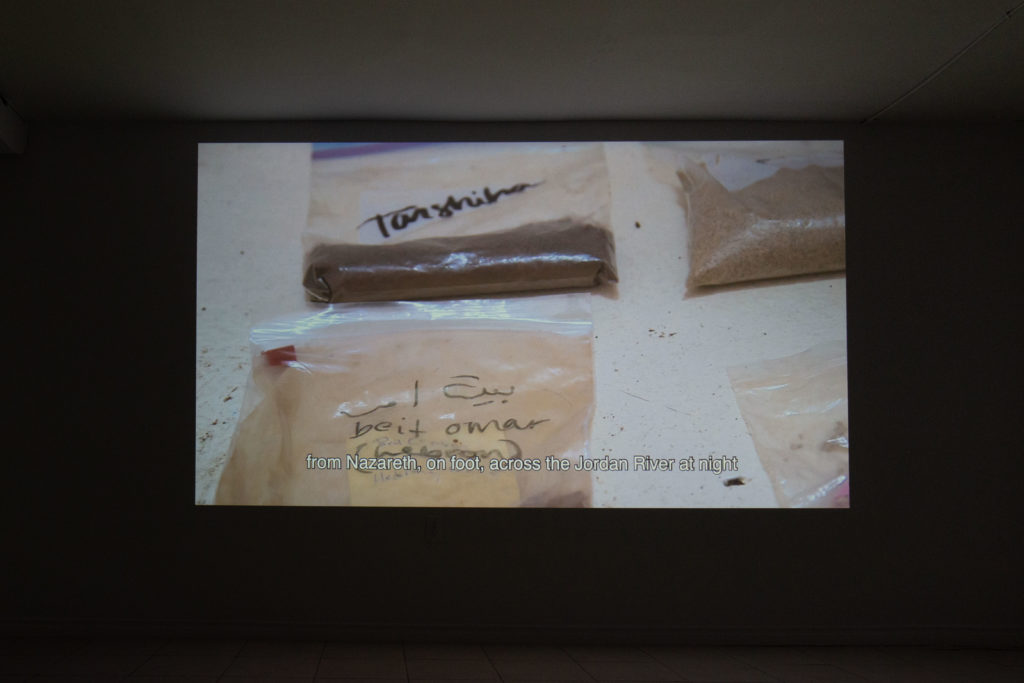

Rana Nazzal, Something from there (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Rana Nazzal, Something from there (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Something from there starts off with the voice of Nazzal’s dad speaking over a black screen, then a photograph, held by a hand, appears:

The truth

I remember a video

of you guys with your mother

on the beach of Tabaria Lake

And this video that I watched,

it really affected me,

because exactly, exactly,

I used to play on that exact beach

with my sister, the teacher, who was killed in the war,

in her school

So,

I remembered the Nakba and Palestine and the sister who was lost

and all of it, get it?

So,

in that moment,

I felt I needed

something from there

The seemingly ambitious yet familiar “something” he refers to holds such a heavy weight. How does one put words to what only a body remembers and longs for? At no point do any of the figures in the film refer to what the “something” is: a piece of land? The smell of soil? The remains of a family member? Moving images of kids filling zip-lock bags with soil, of old trees and of hands that unfold a birth certificate are coupled with Nazzal’s and her dad’s storytelling; I wondered, how is one’s existence documented versus experienced? “A photo has no smell, it’s static, it’s nothing,” Nazzal’s dad says. He speaks of visiting Palestine in 1968, recounting how in his one-day visit—which was supposed to be a month long but he was denied a longer stay despite having the visa—he smelled her. Something from there alludes to how matter resides in a body, how a body remembers, and doesn’t forget.

Installation view of Kalil Haddad’s This Beautiful Room is Empty, 2020. Photo Alison Postma.

Installation view of Kalil Haddad’s This Beautiful Room is Empty, 2020. Photo Alison Postma.

Haddad’s The Beautiful Room is Empty explores the loaded memories of space through his aunt, Marie, (re)visiting her childhood home and recalling the abuse she endured there. Shots of empty rooms of the house, before it was passed to new owners, are coupled with Marie’s anger and pain at her father’s heteronormative and gendered expectations. She recounts hiding with her sister under the bed with the door open so it’s not suspicious, while the viewer is invited to stare at the blank walls and hollowness of the space. She speaks of “sighing out loud [her] resistance.” What have the walls been listening to? What have they absorbed, retained, and released upon a return, a farewell? The steady shots, edited to zoom in slowly on architectural structures—as if one is zoning out, dozing off, accessing what fogs over the mind—are strikingly different than the last shots of Marie. At the end of the film, she stands in the football field of the school she went to, talking about how to capture 45 years of her life in a few minutes: “You don’t think a field is going to cause you to go down memory lane and, you know, expand your politics; it’s just a freaking field.”

I jotted down notes from the films in both Arabic and English: sentences starting from the left, sentences starting from the right. The dissonance that happened when my brain would cheat and read the English subtitles—loan words in Egyptian Arabic, which I grew up speaking, often leave room for misunderstanding in Palestinian Arabic—felt emulated in my notebook. The films’ narratives, mostly told in mother tongues, took their own shape and weren’t morphed to fit a specific audience. They reclaimed belonging and longing, and articulated personal history as social history.

I left the gallery wondering what resides in my body, and in the structures I grew up around. What lies in spaces we don’t visit every day, or in matter we constantly recall? What layers can be found beyond the visual? Stories are embedded in corners, seeds, the backs of cupboards. Belonging resides in smells that have long left their home, and physical spaces that echo sighs from childhoods. These films, hauntingly and beautifully, tapped into the minute and the dear, through zip-lock bags full of soil, pomegranate seedlings, jars of food in a pantry—and “just a freaking field.”

Rana Nazzal, Something from there (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Rana Nazzal, Something from there (film still), 2020. 8 min. Courtesy of the artist.