Why has the success of Caribbean and Caribbean Canadian artists so often relied on exhibiting outside Canada? Victoria-based, Jamaican-born artist Charles Campbell is a skilled multidisciplinary artist with an imaginative mind who constructs compelling spaces for critical discourse. His art practice spans nearly three decades, with an extensive period spent on the west coast of Canada. He has an impressive international exhibition record, including at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, Havana Biennial, Brooklyn Museum and Santo Domingo Biennial; he was also the chief curator at the National Gallery of Jamaica. But “Charles Campbell: as it was, as it should have been” at Wil Aballe Art Projects was his first solo exhibition in Vancouver.

One might expect, given his international experience, that he’d have already had an exhibition at the likes of the Vancouver Art Gallery, which prides itself as one of the the top arts institutions in the Pacific Northwest, or at other public galleries in the region. Campbell shared with me that his identifying as a Caribbean artist in BC often leads others to assume that his oeuvre mainly depicts archaic Caribbean stereotypes, such as palm trees. When he has shown in Canada, at galleries or artist-run events, it has been by his constant self-initiation—aside from exhibitions at Flotilla and Open Space—as he rarely is invited to exhibit despite being a leading artist in Caribbean contemporary art.

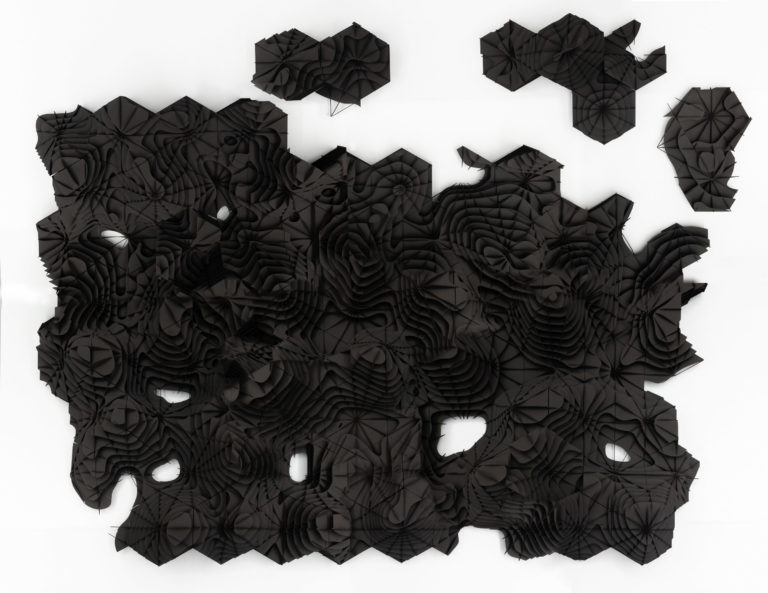

Charles Campbell, Maroonscape 1: Cockpit Archipelago, 2019. Mat board and wood, 2.3 m x 1. 7 m x 60 cm. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, Maroonscape 1: Cockpit Archipelago, 2019. Mat board and wood, 2.3 m x 1. 7 m x 60 cm. Photo: Michael Love.

The lack of a high-profile reception to Campbell’s art in Canada is clearly not an issue of aesthetics; during studio visits, curators, directors and other arts leaders are regularly visually stimulated and excited by the work. Campbell recalls the Victoria International Airport’s Art at the Airport Advisory Committee emphasizing how captured they were by his recent commission and installation, Time Catcher. But the breadth and depth of colonization has been internalized in Canadian culture, and the extent to which Campbell’s work critiques it is often fundamentally misunderstood, or even deemed a threat.

Despite the “othering” of his work in Canada, the methodologies Campbell applies to his artistic process are deeply rooted in contemporary practice. Through his fictitious Jonkonnu performance character Actor Boy, as well as in paintings and sculptural and sound installations, Campbell explores the intercultural boundaries of space and time in search for utopic futures. Perhaps the most compelling part of this exhibition was the Maroonscape series. Maroonscape 1: Cockpit Archipelago (2019) is an intricate sculpture perceived as a broken, asymmetrical hive. It is made of mat board and wood and serves as an architectural map inspired by Jamaica’s Cockpit Country, an area with hills, ridges and deep valleys, where the Maroons settled. The Jamaican Maroons were enslaved Africans who fought, revolted and escaped from the plantations, forming their own free communities. Their resistance proved detrimental to enhancing profits for the British, who eventually signed treaties with the Maroons, granting them land and autonomy in exchange for their peace and support of the colonial militia. Campbell integrates his personal relationship to this landscape with the spirit of resistance to imagine a futuristic model of autonomy against colonial forces.

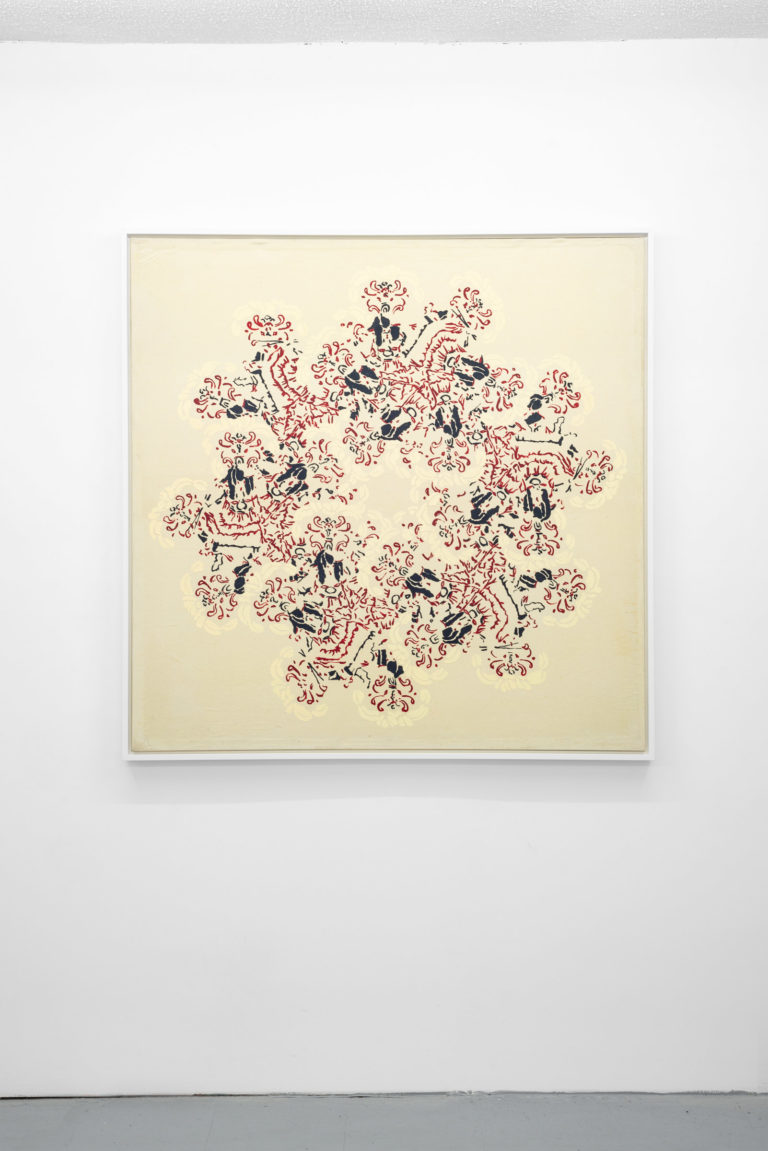

Charles Campbell, Actor Boy I, 2009. Oil on canvas, 1.2 x 1.2 m. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, Actor Boy I, 2009. Oil on canvas, 1.2 x 1.2 m. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, Maroonscape 1: Cockpit Archipelago, 2019. Mat board and wood, 2.3 m x 1. 7 m x 60 cm. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, Maroonscape 1: Cockpit Archipelago, 2019. Mat board and wood, 2.3 m x 1. 7 m x 60 cm. Photo: Michael Love.

Throughout the gallery, the sound installation Maroonscape 2: Yet Every Child (2020) echoed the songs of birds local to Jamaica’s Cockpit Country region. Campbell spent much time recording birds and editing their sounds into little fragments, which were then translated into Morse code and reconfigured into a quotation from Afrofuturist author Octavia Butler. This brilliant integration of sound functions as a multispecies language-in-progress in search of emancipation in the spaces Campbell conceives. Viewers undergo Actor Boy’s method of time travel to become immersed in another utopic future created by Campbell, with each specific trill and tweet of a bird acting as a portal through time and space, one that enables a direct link between our ecological environment and futuristic notions of liberation.

The polarity of the cross-cultural reception of Campbell’s art raises questions about how Caribbean contemporary art is underrepresented more broadly, and why the success of Caribbean and Caribbean Canadian artists often happens outside Canada. Museums and galleries function as institutions of power that define the value of artistic and cultural production through the persistent bad habit of “othering” descendants of Caribbean heritage.

Charles Campbell, “as it was, as it should have been,” 2020. Exhibition view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, “as it was, as it should have been,” 2020. Exhibition view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Photo: Michael Love.

Many Canadians—especially art consumers and institutional gatekeepers—do not view Caribbean contemporary art as relevant or relatable to the established colonial Canadian narrative. The birth of modern art is owed to racialized artists, yet the recognition has not followed. The colonial lens that defined modern art is the same one upholding the merits of contemporary art now; there has been almost no evolution in white imperialist thought that frames so much of the Canadian art world.

If the challenges to colonialism that emerge from Campbell’s conceptual landscapes and multidisciplinary works continue to be reduced to racial and cultural stereotypes perpetuated by Canada’s outdated and complex relationship with the Caribbean, will there be a future for Caribbean art in Canada? What would that look like? Social justice movements have begun to challenge colonial rhetoric, but Charles Campbell reminds us that there is more work to be done.

This article was corrected on March 17, 2021, to acknowledge the work of curators who brought Campbell’s work to Flotilla and Open Space.

During the run of this exhibition, in October 2020, the Vancouver Art Gallery began discussing an acquisition of Campbell’s work for their permanent collection. The purchase of Maroonscape 1 (2019) and the donation of Maroonscape 2 (2020) were ratified by the Board of the Vancouver Art Gallery on February 24, 2021. The author hopes their interest in Caribbean contemporary artists continues.

Charles Campbell, “as it was, as it should have been,” 2020. Exhibition view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Photo: Michael Love.

Charles Campbell, “as it was, as it should have been,” 2020. Exhibition view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Photo: Michael Love.